- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

(Jun 2015) What's In A Symbol? |

“There is hopeful symbolism in the fact that flags do not wave in a vacuum.”

—Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008)

1:

INNOCENCE AND PRIDE

When I was nine, a new television show entranced young boys everywhere. It featured two good ol’ boys from the American South who battled the schemes of a dastardly county commissioner, whose corrupt sheriff would frequently chase the heroes, who always outran them in a souped-up car that was the stuff of young boys’ dreams.

The show was The Dukes of Hazzard, and the car was The General Lee. It was 1979, and I was too young to really get any of the “Southern pride” behind Bo and Luke Duke and their car; all I knew was that Southerners spoke with a drawl, screamed “Yee-hah!” a lot, fired explosive arrows, and lived the rural farm life.

But I knew that not all Southerners had a car like the Duke boys. I knew that The General Lee was named for the leader of the South’s army during the Civil War, but that meant nothing to a fifth-grader who’d only studied as far as the American Revolution. That car was mind-bogglingly awesome. It was a blaze-orange 1969 Dodge Charger with a big “01” on either welded-shut door. I didn’t get that the tune the car’s horn played was “Dixie,” a Southern anthem. And I didn’t understand the meaning behind the design on the roof that I thought was the coolest thing ever.

I heard that it was the “Confederate flag,” but I didn’t know what that meant. I just knew that it was a blue X criss-crossing a red field, with white stars in the blue. It was visually slick and powerfully colorful; its red-white-and-blue design with thirteen stars representing the thirteen original colonies evoked patriotic feelings in me. It was exciting, it was beautiful, and seeing it elsewhere reminded me that it belonged on a super-cool car that drove really fast and jumped over creeks.

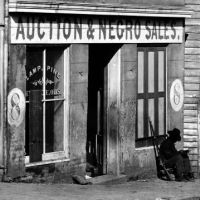

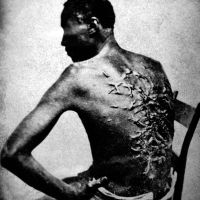

I was probably in high school before my years of learning about the Civil War finally resulted in a realization of just what that flag represented. The Confederate battle flag was used by the secessionist states calling itself the Confederate States of America. Confederate apologists have claimed many alleged reasons for the CSA’s secession attempt, but most are excuses to avoid admitting what’s really the only reason: slavery. Some will disagree, but I’d wonder how many of them are the kinds of people who are apt to fly the Confederate battle flag.

They can claim any alleged reasons that they like—cotton, protectionism, states’ rights, sectionalism, whatever—but these are excuses meant to deflect from the cold reality that the Confederate States wanted to own other people. They wanted to be able to sell them, to overwork them, to abuse them, to rape them, to kill them, and to otherwise treat those people as subhumans, as things to be used as their owners pleased. Now, in a war like that, it’s pretty clear what the Confederate battle flag stood for—but, 150 years later, can we judge that flag the same way?

We absolutely can, based on what it means to others. The Confederate battle flag is deeply offensive to many in the South, and slowly the tide has been turning so that more and more people are tiring of their governments flying such a flag.

On June 17, 2015, Dylann Storm Roof, a 21-year-old white male, entered the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina and opened fire with a .45-caliber handgun. Six women and three men, all African Americans, died, simply because Roof is a segregationist and white supremacist. Roof was apparently self-radicalized; he wasn’t spurred on by any group, but had his own ideas and decided to act on them. People of all colors and cultures were mortified.

And guess what symbol this piece of shit used for his horrific actions?

Yeah, you guessed it: the Confederate battle flag. But that he used that as his symbol should come as no surprise, since that flag was created to represent segregation and white supremacy. I’m willing to bet there’s a Bible involved in Roof’s reasoning somewhere, too, but we’re not talking about directives from imaginary deities here. We’re talking about what this symbol means to so many.

2:

THE POWER OF SYMBOLS

Symbols mean different things to different people. As that nine-year-old boy, without any context for the flag atop The General Lee, to me it was a patriotic design that radiated coolness and power like heat from a blast furnace. And it made that bad-ass orange car look even more awesome as it flew through the air over the creek, with the Duke boys wailing “Yeeeeee-HAH!” and Sheriff Roscoe P. Coltrane diving his police car nose-first into the mud.

Even though I know now how offensive the Confederate battle flag is to so many and how it symbolizes something so disgusting, the nostalgia from my youth is tough to shake. As a design, it’s very well done. It’s artistically elegant, with primary colors offset by white borders and white stars. It’s eye-catching, it’s visually appealing, and its colors evoke American patriotism. Yet I still remember what it truly means, and I’m able to cast it aside in my mind as a symbol I can never honor.

Think about it this way: What if a section of the country thought that the swastika looked marvelous, and decided to hoist flags that featured it? Even if they said that their love of the design had nothing to do with Hitler or Nazism or anything evil, would it be acceptable? Depending on the context, possibly.

Wait—what? Am I claiming that the Confederate battle flag is a worse symbol than a swastika?

Maybe. The swastika isn’t new; long before Adolf Hitler co-opted it for his Nazi Party, it was used for positive and peaceful reasons. But it shouldn’t be the swastika that’s offensive; it should be a black swastika on a white circle on a red flag. It’s the Nazi flag that should be offensive; after all, it’s hard to imagine how anyone could justify raising a Nazi flag for any reason other than white power, Hitler worship, anti-Semitism, world domination, and any of the other hateful things the Nazis stood for.

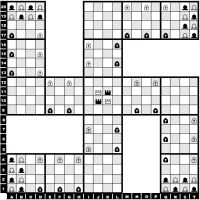

I’m in the process of writing a book of chess variants. While putting it together, it occurred to me that the swastika would make an interesting shape for a chessboard. Since the symbol existed for countless centuries before Hitler, the variant shouldn’t be offensive. I certainly wouldn’t call it “Nazi Chess” or “Swastika Chess”; in fact, I called the variant “Gammadion,” after what the ancient Greeks called the symbol.

But obviously including a chess variant with a board shaped like the gammadion would startle and maybe offend some people who would only see a Nazi symbol. I was so concerned that I nearly cut the variant from the book, but then I realized that I couldn’t cave to one dreadful use of an otherwise positive symbol. As such, I wrote a lengthy introduction to that variant.

3:

THE GAMMADION CHESS VARIANT INTRODUCTION

“It feels strange to have to defend this variant, but for those who flipped open to this page and were horrified at seeing a swastika plastered across it, I feel that I should.

“The swastika is a symbol that has been used for thousands of years in a wide range of cultures—for a variety of purposes, but mostly good or at least neutral. Unfortunately, along came Adolf Hitler, who chose to use it to represent his Nazi party, and the symbol became one of hatred, tyranny, racism, and genocide. The swastika, long an icon of many good things, was thus tarnished as something dark and evil. While I completely understand that, I refuse to let the worldview of one twisted man and his army of monsters forever monopolize a symbol—and one that, in many cultures, still has positive significance.

“I’m also pragmatic; I’m not religious, so when it comes to characters like this I suffer neither from idolatry nor nostalgia. They’re just shapes; what they mean depends on what they mean to different people. If you’re so glued to the idea that the swastika means only evil, then nothing I say here will likely convince you otherwise. But to me it’s just a shape that has represented many things; it has no more personal meaning for me than a cross or a crescent or a six-pointed star. While it’s easy to be offended because a thing means something to you, offense is about belief and intent, and I neither believe in anything particular about the symbol nor have any intention to offend those who believe it’s something bad.

“However, thanks to the popular mortification since Hitler first described his vision for his flag in 1925 in Mein Kampf, I’m certainly not ignorant of what it means to so many. But I’d prefer to reclaim the symbol and reduce the negative power it holds over so many. That’s why it’s featured here. By the way, I’ve called this chess variant Gammadion because that’s what the ancient Greeks called the swastika; it represented four gamma characters (Γ) at right angles. It was prominent in their architecture, as tattoos on priestesses, and as a representation of the four corners of the world.

“As a final note, a brief story: When Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh was about to be executed, he recited the poem “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley. It crushed me, for that is perhaps my favorite poem of all time. I was furious that a monster like that had to ruin it for me and for anyone else who had ever found inspiration in that poem. But I came to realize that if I let some dead asshole like that guy ruin something great, then my mind was forever slave to other people’s ideas defining me. The gammadion isn’t special to me but, like “Invictus,” I won’t let anyone decide for me that it stands for an evil that isn’t representative of me.

“If, after this lengthy introduction, you continue to feel offense at this variant, remember one thing: Offense is about belief and intent. I don’t believe anything about this symbol, and I don’t intend to offend anyone. If you feel offended, there’s nothing I can do about that.”

4:

GOVERNMENT ENDORSEMENT

The same might be said of the Confederate battle flag, except for one key thing: The Confederate battle flag did not have a long history of positive and peaceful uses but was then corrupted for evil purposes during the Civil War. The Confederate battle flag was designed from the ground up to represent secessionist states fighting for their right to own other people. I’m not sure how else to view that symbol.

But like young boys who were entranced by the flag on the roof of The General Lee, I certainly believe that there are many who don’t view the Confederate battle flag as a symbol of slavery and hatred. I think that there are many who really do view it just as a symbol of Southern pride. Perhaps many of them are not racist, who have African American friends, who agree that we’re all equal, who think that slavery is abhorrent, and so forth. I think it’s still in poor taste to fly or wave or otherwise display the Confederate battle flag—at least, once you know what it really stands for—but that’s the choice of the individual.

That all changes when it comes to governments.

In the American South, for years the Confederate battle flag has been flown out of spite, ignorance, and hatred. During the civil-rights era, state governments flew it in opposition to desegregation and equal rights for blacks. I’m talking about the 1950s and 1960s here—a century after slavery was abolished. That we even had to fight for civil rights in the United States that recently deeply disturbs me.

The idea that any government would fly the Confederate battle flag or use Confederate imagery in any way is disturbing, because what that says is that the government continues to endorse the backward thinking that has no place in a civilized society (such as it is). Yet Southern governments have continued to do so. In South Carolina, it was the law for some time that the Confederate battle flag fly atop the statehouse, before public pressure had the legislature move it down to the statehouse grounds. Only recently, when Roof killed nine innocent African Americans, did South Carolina’s elected leadership finally begin taking this issue seriously.

Suddenly, far-right politicians who had previously supported flying the Confederate battle flag have come out to say that it’s time to remove it. Retail giants such as Amazon, eBay, Sears, Target, and even right-wing-friendly Walmart have ceased selling anything featuring the Confederate battle flag. And on June 24, Warner Bros., which owns the rights to The Dukes of Hazzard, announced that it would no longer license any Dukes merchandise that featured the Confederate battle flag.

Retail giants such as Amazon, eBay, Sears, Target, and even right-wing-friendly Walmart have ceased selling anything featuring the Confederate battle flag. And on June 24, Warner Bros., which owns the rights to The Dukes of Hazzard, announced that it would no longer license any Dukes merchandise that featured the Confederate battle flag.

The action in Southern states is steamrolling, and not just for removing the Confederate battle flag but for any images honoring the Confederacy. As of this writing, South Carolina is working to pass legislation to take the flag down for good. Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley is calling for its removal from statehouse grounds. Sen. Roger Wicker wants Confederate imagery removed from Mississippi’s state flag. Kentucky Rep. Andy Barr wants a statue of Jefferson Davis, president of the CSA, removed from the statehouse. And Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal and Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe are pursuing removal of the flag’s image from their states’ license plates.

There is no doubt that a government should never mandate the use of a symbol that is so inextricably linked to slavery and hatred as the Confederate battle flag is—regardless of what people claim it means to them today. While it’s better late than never, it’s shameful that, in 2015, it took yet another nine senseless murders of African Americans to finally reach the tipping point on this embarrassing issue.

5:

SOUTHERN PRIDE?

As for non-government types...

I have no doubt we’ll be hearing from proud Southerners who will claim that liberals are trying to force them to ignore their heritage. When you hear that, call bullshit. It’s not the liberals who wave that flag in support of slavery, in opposition of civil rights, as a symbol of segregation. Only far-right social conservatism can bring us this sort of thoughtless insanity, folks.

For those who truly do feel that the Confederate battle flag is not a vile symbol and that it’s just a symbol of Southern pride: Remember, unlike the gammadion, that flag has no long and proud history of positivity and goodness. And if Southern pride is what really matters, and it’s not about slavery and racism and segregation, then why not come up with a new flag—one that cries out “Southern pride!” without the evil connotations? If you do that, we’ll be left with two sides: those of you flying the new flag, and those who are racist bastards who insist on flying the original.

I sincerely believe that there are many who love that flag who aren’t racists. After the Charleston murders and the fierce opposition to the Confederate battle flag that followed, Ben Jones, who played Cooter on The Dukes of Hazzard, spoke out in support of the flag. Jones runs a few stores called Cooter’s Place, where he sells merchandise related to the show—and he sells those flags, and will continue doing so.

“There’s no reason to change anything,” Jones told the Associated Press. “We despise racism ... It’s not a hateful symbol, and we despise that it’s being used by bigots and hate groups.”

But, Cooter, you’re wrong. It is a hateful symbol, and a racist one from its original roots onward. You might not think of it that way, and I believe you when you say that you don’t. But if you chose to believe that the Nazi flag was a symbol of something good and positive and insisted that your love for it had nothing to do with genocide and white supremacy, I think you could understand why people would be baffled by your love for it.

Change the flag, prideful Southerners. If what matters to you is the good you think the current flag represents, then change it to escape the dark history behind it. It would be easy. Consider the last image with this article. All I did was swap the red and blue colors on the Confederate battle flag. Suddenly, we have something very different: that same design, but with a subtle change that could say, “I abhor the hatred, slavery, racism, oppression, and intolerance of my ancestors, but wish to honor the many things that have been great about the American South.” No more “Confederate.” No more “battle.” Just “Southern Pride flag.” It’s perhaps like the difference between using a gammadion, or using a black swastika on a white circle on a red field. The former is an ancient and often proud symbol; the latter is a symbol of hatred and evil.

I suspect that the true haters would never fly such a bastardization of a flag that has, for them, gone beyond symbolism and into the realm of radical insanity. They’ll always fly the Confederate battle flag—never something with two swapped colors that disrespects their Southern heritage of owning other people!

And, to be fair, there will always be people who will adopt any symbol of Southern pride and declare that the South will rise again, with white people in charge and black people toiling under whips and chains. There will always be symbols that people will rally around to support whatever horror they’re trying to justify.

We can only do so much. And it will probably never be enough.

David M. Fitzpatrick is a fiction writer in Maine, USA. His many short stories have appeared in print magazines and anthologies around the world. He writes for a newspaper, writes fiction, edits anthologies, and teaches creative writing. Visit him at www.fitz42.net/writer to learn more.