- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

September 2012 - The Metaphorical Burning of Books |

Books have changed. Not long ago, printed pages were the norm; now, many people prefer electronic books. Some believe e-books are the end of books, but they’re just a new way of conveying the words to readers, and will likely get more people reading more often. Besides, there’s a far bigger concern in the world of books.

My wife and I used to make regular summer drives to a giant resale shop called The Big Chicken Barn. Located near the Maine coast, this is literally an old chicken barn, its first floor replete with rented booths full of antiques and Americana, and its second floor packed full of books and magazines by the tens of thousands.

But not long ago, my wife got an e-book reader, and she’s mostly lost interest in The Big Chicken Barn. I still visit regularly to peruse the endless shelves for hidden treasures. These can be books I hadn’t read since high school, anthologies from before I was born, or any paperbacks with eye-catching cover art and irresistible back-cover blurbs.

These can be books I hadn’t read since high school, anthologies from before I was born, or any paperbacks with eye-catching cover art and irresistible back-cover blurbs.

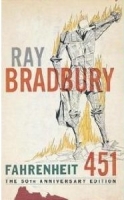

I have a particular affinity for dystopian science fiction—tales set in societies gone awry—and clearly remember the first such book that impacted me. The year was 1987, and the book was Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. The story is set in a near-future society where all books are illegal, and firemen don’t put out fires—they start them, burning down the homes of criminals possessing books. The protagonist, Guy Montag, is a fireman who discovers the value of books and questions the wisdom of their destruction.

The typical interpretation of the book is about government censorship and oppression, although Bradbury said he was commenting on how television was impacting the reading of literature—that the people are responsible, not the government. That was a stunning bit of precognition for 1953, considering how easily people are lost in their electronic devices today—staring at them while walking into traffic or driving on the wrong side of the road, ignoring the world around them in favor of their tiny screens. (Don’t worry, they won’t be around much longer; sooner or later, we’ll have brain implants and be telepathically online constantly, without the distractions of mere handheld devices.

But I’m not here to talk about the dangers of technology. I’m here to talk about book reports in high schools.

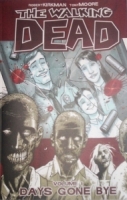

Recently, a co-worker and I were discussing the television show The Walking Dead, which is based on a comic-book series. We’re both avid fans, and she told me that she’d bought the first six graphic novels compiling the comic series. (Graphic novels, if you’re wondering, are extended comic books comprised of original works or comic reprints.) She’d thoroughly enjoyed them, although she joked about being a forty-seven-year-old woman buying comic books.

And then she told me something that totally stunned me: At her daughter’s high school, students are allowed to use The Walking Dead for book reports—indeed, graphic novels in general are fair game. They don’t even have to be illustrated versions of classic literature.

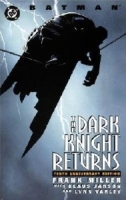

Now, I think comics are great, and some graphic novels are outstanding. V For Vendetta and The Watchmen come to mind, and I think Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns is one of the finest ever. Like radio and television and cinema, the graphic novel is a unique form of storytelling. But they’re not the same as books, especially when they’re adaptations of books. I recall reading an illustrated version of Huckleberry Finn in junior high and, having read the actual novel, I can say the latter was orders of magnitude better than the former.

With this graphic-novel revelation, all I could think of was Fahrenheit 451. Has society finally reached the point where the dumbing down of humanity was now officially part of the educational curriculum? In a country like the United States, where too many kids believe in creationism and can’t balance their checking accounts, and spend their days writing short messages that omit vowels and substitute numbers for words, have we finally thrown in the towel? What’s next—oral reports on today’s Garfield? Essays on this week’s Page Three girls? College dissertations written 140 characters at a time on Twitter?

And, hey, why spend all that time reading a book when we can find abbreviated versions better suited to today’s attention spans? We can read comic versions in a few hours, movie versions in two, episode-of-the-week versions in one. Book burning is the least of our worries, because we’re effectively censoring the classics by summing them up in four-color artwork and capital-letter dialog.

A week after my stunning graphic-novel revelation, I had the pleasure of meeting with one of my teachers from my school days. I work for a newspaper, and was doing a story about the new high school that replaced my alma mater. While we were talking, I happened to glance down at her desk… and saw a graphic novel. At my wide-eyed dismay, my chagrined teacher lamented that this was now considered acceptable reading material in high school. I picked up the graphic novel to have a look.

It was Fahrenheit 451.

As my teacher talked about how at least Bradbury had written the graphic novel’s introduction, I flipped through the pages of comic panels and word balloons. It felt to me like a bastardization of a masterpiece. I felt better knowing the real novel was still out there, but felt worse knowing so many kids would grow up saying they’d read Fahrenheit 451, when they really hadn’t, and might never know just what they’d missed.

According to a USA Today interview in 2009, Bradbury, enthusiastic about the graphic-novel edition, imagined “someone giving it to a 10-year-old kid who then wants to read the original novel,” he said. “That's what good graphic novels can do. They can make you read more.”

I’m sure he’s right. I’m sure some will read the graphic novel and then seek out the book. But I suspect that the vast majority of readers will read that version and be done with it. Reading continues to weaken in a world where “literature” is rapidly becoming badly written blogs and social-media posts. Today’s kids live in a world full of sound bites and video clips; why would they bother going one step further?

Talk about irony. Fahrenheit 451 spoke of the dumbing down of humanity, in a world where literature is burned by the government in the ultimate book-banning censorship. Now, that very book has been dumbed down and, to a certain degree, censored. Everything the book was had been reduced to those panels and balloons, two dimensions where so many more had been.

“It’s the stuff of their generation!” cry the proponents of graphic novels in schools.

We’ve had comic books since 1933. We still read books anyway. And when I was in high school, we were the MTV generation, but they didn’t let us do book reports on the music videos of Michael Jackson.

“It’s easier for kids to understand!” they argue.

That’s because we’re raising a generation of kids who expect to do as little as possible, and we enable that behavior.

“We must open their minds!” they proclaim.

You can do that with books. You can swing their minds open wider than they’ve ever been opened before. Limit them as we are, and we help to keep them closed.

“It’s tough to get kids to read books!” they complain.

It has always been tough for some; teachers have long combated students reading CliffsNotes instead of the assigned books. But it’s time to educate—not merely preside over a classroom.

“We must talk to them on their level!” they trumpet.

No—we talked to them on their level for years of school. High school is where we prepare them for the rest of their lives. They must learn to talk to the rest of the world on our level.

Proponents of comic books as assigned reading in schools completely miss the point of how powerful and inspiring books can be. And they sure as hell completely miss the point of a book like Fahrenheit 451.

Perhaps next we should rewrite the classics in abbreviated Twitter posts. Once they’re preserved forever that way, kids can skim through them whenever they have a few minutes in study hall. That’s assuming they have time between running an app to do their math homework and watching a YouTube video to teach them about their next shop-class project.

We’re approaching the point where nobody will need to bother reading books in their original forms. Once that happens, we’ll be effectively piling up all the books we can find and burning them. Metaphorically, perhaps, but no different.

I still have the hardcover of Fahrenheit 451 that I read in 1987. I could probably rant about this subject for thousands of words more, but I’ll end it here. I’m off to read that masterpiece yet again.

If you haven’t read it, I hope you’ll do the same. Just skip the comic book.

David M. Fitzpatrick is a fiction writer in Maine, USA. His many short-stories have appeared in print magazines and anthologies around the world. He writes for a newspaper, writes fiction, edits anthologies and teaches creative writing. Visit him at www.fitz42.net/writer to learn more.