- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

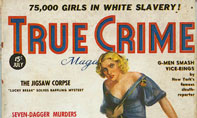

Popular Culture Representations of Crime |

From the perspective of popular culture and the media, and in particular with regard to cinematic representations of crime, it is certainly fair to assert that crime can operate as a source of horror or pleasure for the audience. The cinema is, after all, at its most intrinsic level, a form of entertainment. It is important, however, to recognise the gap that often exists between accurate portrayals of crime (whether or not they are reputed to be 'true' crime accounts or not), and of fictional or stereotypical depictions of crime and criminal behaviour1. In this respect, then, just as the news media may be held accountable for irresponsible reporting or coverage of certain issues, so too could it be argued that filmmakers have a degree of general responsibility in their work, especially when film is capable of influencing mainstream public conceptions and understandings of 'crime', and not just of invoking reactions of 'horror' or 'pleasure'.2

The cinema is a powerful medium, particularly when crime is involved. As a story unfolds on the screen, as soon as it captivates the interest of its audience, film has the potential to directly affect one's emotions, and perhaps, one's own set of beliefs or ideological stance. 3 That is, just as reports of true crime in the general news media may shock or outrage us, so too may representations of such crimes in the cinema. In the same turn, news of a fugitive's capture or of a criminal conviction may satisfy the public's faith in the criminal justice system and provide a sense a pleasure' a reaction which may be evoked from film as well.

The cinema is a powerful medium, particularly when crime is involved. As a story unfolds on the screen, as soon as it captivates the interest of its audience, film has the potential to directly affect one's emotions, and perhaps, one's own set of beliefs or ideological stance. 3 That is, just as reports of true crime in the general news media may shock or outrage us, so too may representations of such crimes in the cinema. In the same turn, news of a fugitive's capture or of a criminal conviction may satisfy the public's faith in the criminal justice system and provide a sense a pleasure' a reaction which may be evoked from film as well.

In the news media, the links between the content of crime news and viewers' beliefs and attitudes about crime are difficult to establish, and even more difficult to establish in relation to their impact upon changing public policy in the criminal justice system. 4 The same can be said for crime films. Some individuals will be more susceptible to media influences than others, based upon such factors as education, gender, religion, class, race, and their own personal experiences with crime. 5 Audiences are of course not devoid of any independent forms of thought, nor necessarily influenced by every film they see, however, it is nonetheless important to recognise that images in popular culture certainly may play a role (however difficult it is to determine exactly) in forming what the public and the judiciary think about crime and criminality in general. 6

Many different specific examples exist of ways in which films depicting crime or addressing issues of criminality have been reputed to have impacted upon the behaviour of the public or upon public policy. In the United States in 1991, a riot broke out in a suburb of Chicago between police and some sixty to seventy African'Americans outside of a cinema that had been screening the movie Boyz in the Hood, a film dealing with issues of gang violence and police racism. Similarly, racial tensions were aroused in Australia upon the release of Romper Stomper, also in 1992; and Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers (1994) stirred considerable controversy because its content was considered to be too horrific for many audiences to bear. Less dramatic is the account provided by Kathleen Daly of a young female criminology student that explained to her: ...I want to be Jodie Foster... (referring to Foster's 1991 role as an F.B.I agent in Silence of the Lambs). 7 Whilst these are very specific examples, and therefore perhaps remote, they create an interesting set of examples which may be compared to the similar impact which the news media is reputed to have upon the public and policy considerations.

Many different specific examples exist of ways in which films depicting crime or addressing issues of criminality have been reputed to have impacted upon the behaviour of the public or upon public policy. In the United States in 1991, a riot broke out in a suburb of Chicago between police and some sixty to seventy African'Americans outside of a cinema that had been screening the movie Boyz in the Hood, a film dealing with issues of gang violence and police racism. Similarly, racial tensions were aroused in Australia upon the release of Romper Stomper, also in 1992; and Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers (1994) stirred considerable controversy because its content was considered to be too horrific for many audiences to bear. Less dramatic is the account provided by Kathleen Daly of a young female criminology student that explained to her: ...I want to be Jodie Foster... (referring to Foster's 1991 role as an F.B.I agent in Silence of the Lambs). 7 Whilst these are very specific examples, and therefore perhaps remote, they create an interesting set of examples which may be compared to the similar impact which the news media is reputed to have upon the public and policy considerations.

As in films that are concerned with issues of crime, there is no relationship between the frequency of crimes reported to the police and the frequency of crime news stories. 8 This is often due to the nature of the news media, where crime news is regularly used as filler, and may also be sensationalised or exaggerated in order to attract an audience's attention. 9However, whilst such news is arguably 'horrifying' or 'pleasing' its receptive audience, it could also have the consequence of giving the general public an impression that certain crimes occur more often than in fact they may, purely because they are receiving a specific amount of media exposure.10 The obvious danger in such an outcome is that an impressionable public may be ill'informed of the true nature of crime in our society, and as such, may place undue pressure upon policy makers for reform or action in areas of our criminal justice system that do not necessarily deserve our most immediate attention. 11

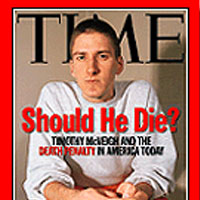

The prolonged media exposure in the United States of the 1995 Okalahoma Bombing and the sentencing trial of Timothy McVeigh is a strong case in point. As coverage of his trial commenced and the television movie of McVeigh's story went into production, a considerable amount of the news coverage presumed ahead of his sentencing that he would be sentenced to death. Both 'real' reporting and the movie depiction used the case as a strong endorsement for the death penalty and tougher Federal laws for such offences as McVeigh was charged. 12 In a TIME'CNN poll from June 1, 1997, 78 per cent of the respondents wanted McVeigh to receive the death penalty. 13

The prolonged media exposure in the United States of the 1995 Okalahoma Bombing and the sentencing trial of Timothy McVeigh is a strong case in point. As coverage of his trial commenced and the television movie of McVeigh's story went into production, a considerable amount of the news coverage presumed ahead of his sentencing that he would be sentenced to death. Both 'real' reporting and the movie depiction used the case as a strong endorsement for the death penalty and tougher Federal laws for such offences as McVeigh was charged. 12 In a TIME'CNN poll from June 1, 1997, 78 per cent of the respondents wanted McVeigh to receive the death penalty. 13

When films and the media at large give an indication of a supposed 'crime trend', provoke widespread anxiety about crime, or engender policy developments merely because a particular news story or film became a celebrated case or a popular blockbuster, a need perhaps arises to address issues such as media responsibility, and whether or not a profession like criminology should be playing a more direct role in these areas. This would be particularly useful as a means of offering political and socio'economic evidence in explanations of crime since such conditional factors are often either left out or dealt with in an unsatisfactory manner in news reports and many crime films. 14 Unfortunately, it is not an easy nor necessarily appropriate measure to allow either criminologists or crime and justice scholars to intervene in the journalism or filmmaking process, by the very fact that their skills and level of experience are not those that are required in the particular industries. 15As Janet Chan has offered:

...Criminological research is especially attractive to media journalists because anything related to crime, deviance and illegality is automatically newsworthy. However, there is a limit to which the media can translate the 'boring language' of social research into a colourful, exciting piece of news....16

In addition, it is worth considering the notion that whilst a comprehensive criminological perspective may therefore never be able to comfortably fit into the framework of the cinema and the news media, representations in film and elsewhere in the media that are displaced from reality may offer the criminologist an insight into crime and criminal behaviour that could not have been ascertained via scientific and academic approaches. 17

Film essentially offers a means of escapism. That is, in the confines of the theatre, an audience can forget the problems of the real world and enjoy the broad scope of a filmmaker's imagination. Where crime is the subject matter which is involved, however, certain problems may arise. Granted, from a criminological viewpoint, crime fiction may offer a perspective that social science and academic reporting of knowledge cannot provide 18, yet it can also present untrue and exaggerated representations of 'true' crime events, and sensationalist accounts of fictional crime, which can give the wider public an impression of the causes, nature and incidence of crimes which is far from the truth. This may, in turn, encourage undue anxiety in the community about crime, and subsequent changes or reforms in specific aspects of the criminal justice system at the expense of those areas that are in more dire need of redress, but that have not been deemed as newsworthy or potentially 'popular' enough to receive the appropriate attention.

Film essentially offers a means of escapism. That is, in the confines of the theatre, an audience can forget the problems of the real world and enjoy the broad scope of a filmmaker's imagination. Where crime is the subject matter which is involved, however, certain problems may arise. Granted, from a criminological viewpoint, crime fiction may offer a perspective that social science and academic reporting of knowledge cannot provide 18, yet it can also present untrue and exaggerated representations of 'true' crime events, and sensationalist accounts of fictional crime, which can give the wider public an impression of the causes, nature and incidence of crimes which is far from the truth. This may, in turn, encourage undue anxiety in the community about crime, and subsequent changes or reforms in specific aspects of the criminal justice system at the expense of those areas that are in more dire need of redress, but that have not been deemed as newsworthy or potentially 'popular' enough to receive the appropriate attention.

Footnotes:

1. See Jenni Millbank, ...From Butch to Butcher's Knife: Film, Crime and Lesbian Sexuality..., Sydney Law Review, 18 (1) December 1996, 451'473.

2 See James Monaco, Chapter Six, ...Media..., in How To Read A Film, Oxford University Press, 1977, pp.335'391.

3 Millbank, op.cit., p.452.

4 Janet B L. Chan, ...Systematically Distorted Communication? Criminological Knowledge, Media Representation and Public Policy..., Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, Special Supplementary Issue, 1995, 23'30, at p.23.

5 Kathleen Daly, ...Celebrated Crime Cases and the Public's Imagination: From Bad Press to Bad Policy?..., Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, Special Supplementary Issue, 1995, 6'22, at pp.11'12.

6 Millbank, op.cit., p.452.

7 Daly, op.cit., p.8.

8 Ibid., p.9.

9 Explanations of crime and deviance may also be inadequately explained in several cases. See Richard V Ericson, Patricia M. Baranek, and Janet B.L Chan, Representing Order: Crime, Law and Justice in the News Media, University of Toronto Press, 1991, p.353.

10 As an example, the recent commercial successes of Silence of the Lambs, Copycat, Seven and Scream (all of which are films that deal with serial killers) obviously cannot be taken to suggest that serial crimes are necessarily on the increase.

11 Chan, op.cit., p.23.

12 See James Collins, ...Day of Reckoning..., TIME, No.24, June 16, 1997, pp.30'33. See also Eric Pooley, ...Death or Life?... TIME, No.24, June 16, 1997, pp.35'40.

13 Ibid., p.35.

14 Daly, op.cit., p.15, also pp.16'17.

15 Particularly in respect of the unfamiliarity that a criminologist would be quite likely to have with the writing styles of news formats, and the general operation of mass media institutions. Ibid., p.17.

16 Chan, op.cit., p.28.

17 Female detective fiction in particular has helped to sharpen our sense of the current gender imbalance, offering us a ...... heightened sense of the claustrophobic nature of conventional female life.... Ngaire Naffine, Feminism and Criminology, Allen and Unwin, 1997.

18 Daly, op.cit., p.17.