- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

Examining Culture and Popular Culture In History — The Scholarship and Legacy of Lawrence W. Levine |

The terms culture and, in particular, popular culture, are open to such a broad range of interpretations that any authoritative definition of them has largely proven to be elusive, if not contentious.  Some historians have even dismissed attempts to define popular culture at all, and instead have concentrated on approaches rather than any strict meaning.1 Since his first publications in the 1960's, the late Lawrence W. Levine's scholarship produced a definition of culture and, in turn, popular culture which increasingly became accepted by mainstream academia (even if his subject matter was not). Levine identified culture not as something that is fixed; rather it is a process that is the product of interchange between past and present, and it is formed and re-formed as a result of interaction with other forms of culture.2 According to Levine, then, popular culture is what his colleague Raymond Williams recognized as that which has been created and adopted by the majority, and as such is "widely practiced, watched, heard, read, generally accepted and approved by the majority."3

Some historians have even dismissed attempts to define popular culture at all, and instead have concentrated on approaches rather than any strict meaning.1 Since his first publications in the 1960's, the late Lawrence W. Levine's scholarship produced a definition of culture and, in turn, popular culture which increasingly became accepted by mainstream academia (even if his subject matter was not). Levine identified culture not as something that is fixed; rather it is a process that is the product of interchange between past and present, and it is formed and re-formed as a result of interaction with other forms of culture.2 According to Levine, then, popular culture is what his colleague Raymond Williams recognized as that which has been created and adopted by the majority, and as such is "widely practiced, watched, heard, read, generally accepted and approved by the majority."3

Critical to Levine's approach to cultural history was recognition of 'high' culture, which stands in contrast to popular 'middle' or 'low' cultures. High culture in the United States, Levine argued, was a construct of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries of the social and intellectual elite of America,4 and indeed Levine was very much involved in what had become an international debate against such conservative academics as Allan Bloom who were critical of popular culture and identified its recent emergence in educational institutions and curriculums as a signal of intellectual decline, far removed from the more traditional 'high culture' emphases of the past.5 To understand Lawrence W. Levine's perception of history it is necessary to understand his origins and influences, and the developments that took place in his ideology, as reflected in four of his major books in particular. The sum result of Levine's work was to elevate interest and respect for popular culture as a legitimate area of academic study, and by so doing he ensured that the past lives of ordinary men and women had not been lost amidst a historical landscape that had traditionally placed a premium merely upon important dates and famous leaders.

Lawrence W. Levine was born in New York City in 1933, the son of Jewish immigrants from Lithuania and Odessa. He recalled, "I grew up in Manhattan in a neighborhood that was largely composed of Jews, Greeks, and Irish-Catholics, who to me looked like the Americans in the neighborhood because they were the most assimilated."6 Levine stated that he developed an acute awareness of his own cultural origins and of the assimilation of these cultures into that of mainstream America from a very early age, and such influences were to remain with Levine throughout his studies at the  City College of New York and later Columbia University.7

City College of New York and later Columbia University.7

At Columbia, Levine wrote his dissertation under the direction of William Hofstadter on the subject of the life of the American politician and lawyer William Jennings Bryan, and it was the last years of Bryan's life which were the focus of Levine's first book, published in 1965, Defender of the Faith.8 Levine had served as an assistant professor at the University of California, Berkeley, since 1962, and the atmosphere of the period certainly played no small part in influencing his ongoing projects into cultural history, particularly as the Berkeley campus in the 1960's was the site for the burgeoning student movement of the era, and subsequently for considerable radical political and social ferment.9 During this period Levine was influenced considerably by the civil rights movement to attempt an expansive study into an area he had been interested in for some time — the folk and folklore of African Americans. The result of Levine's research, spanning over a fifteen-year period, was his most critically acclaimed book, Black Culture and Black Consciousness, published in 1977.10

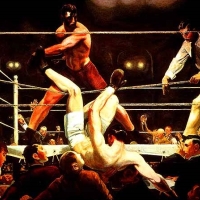

In Highbrow/Lowbrow — The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America, published in 1988, Levine attempted to further what he identified as America's 'cultural independence' by freeing it from the constructs of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, namely the labels 'highbrow', 'middle-brow', and 'low-brow', used by certain intellectuals to categorize other members or elements of society.11 Levine was inspired to write Highbrow/Lowbrow when his research for an earlier essay into the influence of Shakespeare in America revealed that at one time, during the nineteenth century, Shakespearean plays were considered entertaining by virtually all segments of the population in America.12 In his subsequent book, Levine elucidated that the values espoused in Shakespeare's writings meshed with those of nineteenth century Americans and that the love of Shakespeare's works, including burlesques and parodies of them, knew no cultural boundaries.13 Towards the end of the century, however, Levine proposed that lovers of European culture began to approach the arts as something exclusive that must be taught in order for them to be appreciated.14 The result: the fine arts (including other pursuits which Levine recognized as being part of this 'shared culture', including the opera, symphony orchestras and museums) eventually were reserved for a select group (the highbrows) and out of the ready reach of the common man (or lowbrows).15 Thus, Levine asserts, came the existing hierarchy of culture in America today.

Reaction to Highbrow/Lowbrow was mixed, but this is undoubtedly because its audience would largely be considered 'highbrow'.16 There is, however, some difficulty in accepting Levine's notion that parody of Shakespeare implied that the audience was familiar with his work, allowing for the existence of some kind of 'shared culture' in the nineteenth century — a concept that is perhaps difficult to envision.17 Nonetheless, the book raised several important arguments against the dangers of denigrating other cultures without truly having understood them, and above all, Levine was able to show, irrefutably, the changing nature of culture and the term 'culture' itself over time, and he continued to challenge perceptions of what was 'worthy' of serious study by historians.18

Reaction to Highbrow/Lowbrow was mixed, but this is undoubtedly because its audience would largely be considered 'highbrow'.16 There is, however, some difficulty in accepting Levine's notion that parody of Shakespeare implied that the audience was familiar with his work, allowing for the existence of some kind of 'shared culture' in the nineteenth century — a concept that is perhaps difficult to envision.17 Nonetheless, the book raised several important arguments against the dangers of denigrating other cultures without truly having understood them, and above all, Levine was able to show, irrefutably, the changing nature of culture and the term 'culture' itself over time, and he continued to challenge perceptions of what was 'worthy' of serious study by historians.18

Levine expanded upon his thesis on cultural hierarchy and the conservatism in American historiography further in a series of essays between 1989 and 1993,19 and this work culminated in the publication of his book The Opening of the American Mind,20 which was a response to conservative academics such as Allan Bloom. The study focused upon the state of higher education in the United States, and was indicative of the tremendous impact that Levine and other cultural historians had on the study of American history. According to Levine, changes in academia since the 1960's had been all to the good as more students from more diverse backgrounds were studying a wider range of ideas, events and texts than ever before. Levine's study attempted to demonstrate that since the colonial period to the present, there had never been a consensus about the curriculum or the canon, and that the quality of humanities education in the 1990's far surpassed anything offered previously.21 Years earlier, Levine had asserted that he believed university students in the 1980's were brighter than those who had studied twenty or thirty years earlier, but he quickly added "though this is a minority view of the way college education is going in America."22 By the 90’s, however, according to Levine, the 'opening up' of education in the United States and of a changing society were inextricably linked, and new ideas in the university were the only intellectually responsible responses to a changing America, and particularly a multicultural America.23

The book caused somewhat of a furor because of its sharp contrast to the criticisms of such writers as Allan Bloom and Christopher Lucas, whose conservative study, Crisis in the Academy, was released in September 1996.24 Thorough academic review of The Opening of the American Mind assessed, however,  that Levine offered another valuable contribution to the debate concerning the development and recognition of cultural history and the study of popular culture in America.

that Levine offered another valuable contribution to the debate concerning the development and recognition of cultural history and the study of popular culture in America.

Until his death in 2006, Levine maintained his position that historians are inevitably influenced by the values and predispositions of the larger society in which they are writing, but that this should not allow for resistance when new interpretations are forwarded concerning which events and which people should constitute the focus of the historian's study.25 Rather, Levine argued that history should be viewed in the same way the sciences are viewed- as new areas are explored and researched, we must accept that science gradually becomes more and more complex. In the same way, "whilst historians neither can nor want to claim the same level of complexity and abstraction attained by Albert Einstein and his colleagues... historians will be in no position to operate effectively if we ourselves do not strive to increase not only our tolerance for and acceptance of the cultural complexities of the past but our tolerance for and acceptance of the complexities and ambiguities of our own profession."26

Lawrence W. Levine's approach to history was undeniably cultural, and based upon his determination to ensure that we recognize the inherent value of studying areas beyond the traditional and more restrictive 'great men, wars and dates' syllabus of yesteryear. According to Levine, to teach a history that excludes large areas of American culture and ignores the experiences of significant segments of the American people, merely because of the existence of artificial cultural constructs, is to teach a history that "fails to touch us, that fails to explain America to us or to anyone else".27 Throughout his career, Levine received significant criticism and opposition, particularly from right wing academics, and even as many of their notions of what constitutes 'good' culture and what does not, have, at times appeared absurd, Levine always recognized the importance in addressing criticism to ensure the debate about popular culture was maintained and expansive, and that discussions of the subject were not taking place in some "academic vacuum" apart from the outside world.28

Some aspects of Levine's work certainly warrant genuine criticism. Levine never, for instance, really addressed the rise of a 'middlebrow' culture in America, nor did he consider the concept of 'class culture' as opposed to phrenologically derived distinctions of culture. Further, as discussed by T.J Jackson Lears, Levine failed to deal with the fact that so-called 'popular' culture or, perhaps more appropriately, 'mass culture', is not really controlled by ordinary people to the extent that managerial elites exercise influence over such matters.29 These weaknesses are overshadowed, however, by the sheer impact  of Levine's scholarship over the last several decades. Today, educational institutions are revising their curriculums at a rapid rate in the areas of literature, history, art history, music, philosophy, anthropology, film, and so on. Whole literary movements and periods have been recovered or redefined, and the inaccurate and biased historical accounts which were prevalent just a few decades ago have been replaced by more critical and better researched histories.30 By encouraging the expansion of the boundaries of cultural study, Lawrence W. Levine played no small part in this new era of exciting intellectual ferment that has offered a more complete, honest, and authoritative view of our past.

of Levine's scholarship over the last several decades. Today, educational institutions are revising their curriculums at a rapid rate in the areas of literature, history, art history, music, philosophy, anthropology, film, and so on. Whole literary movements and periods have been recovered or redefined, and the inaccurate and biased historical accounts which were prevalent just a few decades ago have been replaced by more critical and better researched histories.30 By encouraging the expansion of the boundaries of cultural study, Lawrence W. Levine played no small part in this new era of exciting intellectual ferment that has offered a more complete, honest, and authoritative view of our past.

End Notes:

- Bob Scribner, cited in Richard Waterhouse, Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: A History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788, Longman Books, 1994, p.ix.

- Lawrence W. Levine, Highbrow/Lowbrow- The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America, Harvard University Press, 1988, p.33. Note also Waterhouse, op.cit., p.ix.

- Raymond Williams, in Ibid., p.x.

- Levine, 1988, op.cit., p.30.

- As discussed in Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind, Simon and Schuster, 1987. See also Ronald Edsforth and Larry Bennett (eds.), Popular Culture and Political Change in Modern America, State University of New York Press, 1991, pp.170-175.

- David Goodman and Shane White, "The Future is Secure; It's Only the Past That's Uncertain- An Interview With Lawrence W. Levine", Australasian Journal of American Studies, 1988, 7(2), pp.22-32, at p.22.

- Ibid., pp.23-25.

- Lawrence Levine, Defender of the Faith: William Jennings Bryan; The Last Decade, 1915-1925, Oxford University Press, 1965.

- Levine had become involved in the civil rights movement in California and particularly the Berkeley free speech movement from its earliest stages of development. Goodman and White, op.cit., pp.25-27.

- Levine, Lawrence W. Black Culture and Black Consciousness, Oxford University Press, 1977. favorable reviews of Levine's book were provided in "Review by Jerry H. Bryant", The Nation, March 12, 1977, pp.311-313, and in New Republic, 'Review', Dec.3, 1977, p.25.

- Levine, 1988, op.cit., See pp.221-222.

- Levine, Lawrence W. "William Shakespeare and the American People: A Study in Cultural Transformation", American Historical Review, 1984, 89(1), pp.34-66.

- Levine, 1988, op.cit., pp.21-22.

- This was due to a number of factors, including the decline of the oral tradition in the United States, the impact of immigration on changes in the language, and changes in taste and style. Ibid., See pp.30-45.

- Ibid., p.9.

- Note Tony Tanner's scathing criticism of Highbrow/Lowbrow presented in The London Times Literary Supplement, "Review" July 14-20, 1989, p.767.

- Levine's perception of a shared culture in the nineteenth century particularly prompted the criticism that there is an element of sentimentality in the study. Ibid., p.767. See also Shirley Samuels (ed.), The Culture of Sentiment- Race, Gender, and Sentimentality in Nineteenth-Century America, Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Levine, 1988, op.cit., p.243.

- See Lawrence W Levine, "Jazz and American Culture", Journal of American Folklore, 1989, 102 (403), pp.6-22, also "AHR Forum- The Unpredictable Past: Reflections on Recent American Historiography", American Historical Review, 1989, 94 (3), pp.671-679.

- Lawrence W. Levine, The Opening of the American Mind: Canons, Culture, and History, Beacon Press, 1996.

- As discussed in Gregory Jay, "Mercenaries of the Culture Wars", In These Times, Sept.30, 1996, pp.1-3, at p.1.

- Goodman and White, op.cit., p.25.

- Ibid., p.3. Note the discussion of the construction of ethnic memory in John Bodnar, Remaking America- Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century, Princeton University Press, 1992, pp.41-77.

- Christopher Lucas, Crisis in the Academy: Rethinking Higher Education in America, St. Martin's Press, 1996.

- Levine, "Jazz and American Culture", op.cit., p.6.

- Levine, 1989, op.cit., p.677, p.679. This was a view Levine had forwarded previously in Goodman and White, op.cit., pp.31-32.

- Lawrence W Levine, "Clio, Canons, and Culture", The Journal of American History, Dec. 1993, 80 (3), pp.849-867, at p.867.

- Levine, 1989, op.cit., p.676.

- Levine, Lawrence W. "AHR Forum — The Folklore of Industrial Society: Popular Culture and Its Audiences", p.1424.

- Jay, op.cit., p.1.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Bloom, Allan. The Closing of the American Mind, Simon and Schuster, 1987.

Bodnar, John. Remaking America — Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century, Princeton University Press, 1992.

Edsforth, Ronald., and Bennett, Larry (eds.). Popular Culture and Political Change in Modern America, State University of New York Press, 1991.

Goodman, David., and White, Shane. "The Future is Secure; It's Only the Past That's Uncertain- An Interview With Lawrence W.Levine", Australasian Journal of American Studies, 1988, 7(2), pp.22-32.

Jay, Gregory. "Mercenaries of the Culture Wars", In These Times, Sept.30, 1996, pp.1-3.

Levine, Lawrence W. Defender of the Faith: William Jennings Bryan; The Last Decade, 1915-1925, Oxford University Press, 1965.

Levine, Lawrence W (ed. with Richard M. Abrams). The Shaping of Twentieth- Century America: Interpretive Essays, Little, Brown, 1965.

Levine, Lawrence W (ed. with Robert Middlekauff). The National Temper: Readings in American Culture and Society, Harcourt, 1968.

Levine, Lawrence W. Black Culture and Black Consciousness, Oxford University Press, 1977.

Levine, Lawrence W. Highbrow/Lowbrow — The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America, Harvard University Press, 1988.

Levine, Lawrence W. The Unpredictable Past: Explorations in American Cultural History, Oxford University Press, 1993.

Levine, Lawrence W. The Opening of the American Mind: Canons, Culture, and History, Beacon Press, 1996.

Levine, Lawrence W. "William Shakespeare and the American People: A Study in Cultural Transformation", American Historical Review, 1984, 89(1), pp.34-66.

Levine, Lawrence W. "AHR Forum — The Unpredictable Past: Reflections on Recent American Historigraphy", American Historical Review, 1989, 94(3), pp.671-679.

Levine, Lawrence W. "AHR Forum — The Folklore of Industrial Society: Popular Culture and Its Audiences", American Historical Review, 1992, 97(5), pp.1369-1430.

Levine, Lawrence W. "Jazz and American Culture", Journal of American Folklore, 1989, 102 (403), pp.6-22.

Levine, Lawrence W. "Clio, Canons, and Culture", The Journal of American History, Dec. 1993, 80 (3), pp.849-867.

Lucas, Christopher. Crisis in the Academy: Rethinking Higher Education in America, St. Martin's Press, 1996.

Rubin, Joan Shelley. Review of L.W Levine's 'The Unpredictable Past: Explorations in American Cultural History", American Historical Review, 1994, 99(3), pp.958-959.

Samuels, Shirley (ed.). The Culture of Sentiment — Race, Gender, and Sentimentality in Nineteenth-Century America, Oxford University Press, 1992.

Waterhouse, Richard. Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: A History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788, Longman Books, 1994.