- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

Dive Tuvalu |

The sound of the motors slowly fades. Strong brown hands tie our boat to the palm tree, the decaying fronds waving at us from just below the surface of the pale green water. Moses clambers back on board, rocking the dinghy. Little waves lap against the hull. The seven of us begin to force our extremities into perpetually damp boots and gloves. Claire, the guide, gestures at the open ocean. “Okay guys, we’re sitting right above the main settlement of Tuvalu now. We’ve got a little orientation video to show you and then we’ll buddy up and head down.”

I stop trying to zip up my left boot -I think it’s broken anyway- and watch as Claire fishes a portable plasma card from her dive bag and plugs it into the hybrid motors of our outboard. I hope this is short because I’m quite eager to-

I stop trying to zip up my left boot -I think it’s broken anyway- and watch as Claire fishes a portable plasma card from her dive bag and plugs it into the hybrid motors of our outboard. I hope this is short because I’m quite eager to-

Great.

If I wanted to see traditional Tuvalu singing I would have stayed in Wellington. This one group of Islanders has been camped outside parliament for months. Apparently the settlements are too far out of the cities for them to find work. The government is apologetic but honestly, you try finding space for close to a million people. In New Zealand.

There is a god-awful hiss as one old guy checks that his regulators are working. My dad told me once that if you are cornered by a shark swim towards it and press on the purge valves. The sound is worse underwater. I bet the old guy’s a really messy diver. I hope I don’t get buddied with him. He’s not even watching the video, he’s looking at the sea. “What are all those orange buoys?” An American accent. Figures.

“Well, it’s mentioned in the video, but those are all the penetrable structures on the island. Two homes, a few stores and the government buildings. We’ll be heading there on the first dive.” Claire points out each buoy.

“What about sharks?”

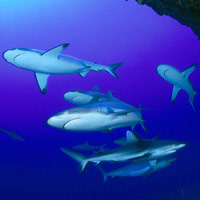

Claire smiles. “You’ll see plenty.” I changed my mind, I’m going with the old guy. “Just reefies, mostly. They’re scavengers and right here they’ve got a whole country to go over. We haven’t seen anything too big in the last couple of months but just to be on the safe side we’ve got some repellent for your wetsuits. Don’t matter how big they are, they’ll swim right past you and won’t even look at you.” Claire pulls a couple of aerosol cans from her magic dive bag.

I hate rolling backwards out of dive boats and I never go first. I know it’s so none of your equipment gets caught and pulled off but it seems somehow showy. Plus I’m scared I’ll land on something nasty. When I was younger I read about a DOC worker that rolled right onto a Great White off Hawke’s Bay. So I was one of the last into the water.

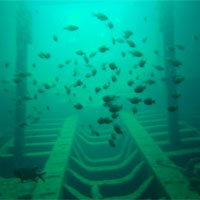

After a quick check of everything I emptied my buoyancy vest and slowly descended beside the palm tree, following the plumes of bubbles beneath me that poured from the other divers’ regulators. I checked my gauges and remembered what Claire had said after the video had finished. “Most of the island is only ten to twelve metres deep so set your mix for a shallow dive and you can pretty much stay down there as long as you want. Moses will stay with the boat if you want to return earlier but we should all aim to be back on the surface in about fifty five minutes.”

After a quick check of everything I emptied my buoyancy vest and slowly descended beside the palm tree, following the plumes of bubbles beneath me that poured from the other divers’ regulators. I checked my gauges and remembered what Claire had said after the video had finished. “Most of the island is only ten to twelve metres deep so set your mix for a shallow dive and you can pretty much stay down there as long as you want. Moses will stay with the boat if you want to return earlier but we should all aim to be back on the surface in about fifty five minutes.”

Boy, she wasn’t wrong about the sharks, either. I could see four already, winding between the buildings that were slowly emerging from the blue. Like she said, they were all small reef sharks. I guess there’s not enough fish around to attract the big ones. That was one of the reasons Tuvalu was eventually sold. The survivors couldn’t even use the water above it for fishing. What did the new owners do with it? Started charging for dive tours. $4999 plus GST ex Auckland, four days, five nights, all incl.

According to the Herald it was the bargain of the season.

I descended to about roof level, not that there were many left. Most were long since gone, either shorn off by ocean surges or rusted through and lying on the seabed in what was once somebody’s home. Every ruined surface was covered in a thin film of electric green. Seaweed with a buzz cut. Rubbery, flesh-pink soft coral sprouted from living rooms. In one house a moray eel had taken up residence in a toilet bowl. He watched me, slack-jawed and menacing, as I swam through the bathroom and followed the others out the back door onto the main street. Ahead of us, stretching in a curving arc across the road, was a line of sandbags. I remember seeing that wall on the news. Crowds of brown children around it, thigh high in water, waving happily at foreign reporters as they motored past.

After a particularly bad tropical storm, Tuvalu had flooded. There were more than a few deaths. The waters calmed but they did not recede below half a metre. It was decided that the time had come for a full evacuation. Foreign soldiers built these sandbag levees -like the one I was swimming over- trying to slow the rising sea. World leaders debated exactly where they would put five million wet Pacific refugees. The sea continued to rise. I’m surprised the sandbags have held up so well, to be honest.

I want to touch the ground behind it. The fingers of my dive gloves kick up little puffs of sand, like a lunar landing module. People walked here. People used this ground. This was a real place and now it’s just sand. I pull myself along the sand with my fingers, trying to put some use back into the ground.

A little way off, Claire and the others are cutting across a bigger expanse of sand (a sporting field, maybe?) on their way to the largest pile of ruins. I was right about the American being a messy diver. His fins are kicking up so much sand he reminds me of a cartoon mouse in a sombrero. I give the group a wide berth and make my way alone towards the eastern side of the large ruins. I hope Claire was right about that wetsuit spray.

Ah. These are the government buildings, I remember these as well. I suppose if the third storey hadn’t collapsed it would still be peeking above sea level, a rusting pixel surrounded by limitless blue. Two large vertical holes –I’m guessing they were floor to ceiling windows- offer access to the darkened interior. I grasp for my torch, floating beside me on a rope attached to my buoyancy vest. Its light falls on a large staircase just inside the windows, winding from the seabed to the remains of the third floor.

Feeling less brave than I probably looked, I kicked my fins and swam towards the closest window. After all, this is what I told my brother I was coming to see when we met for coffee at that new place in Auckland.

“Five grand? That’s not bad.”

“According to the Herald it’s the bargain of the season.”

“Yes, but don’t you think it’s just a little bit ghoulish? Picking over the remains of an entire culture.”

“Yes, but don’t you think it’s just a little bit ghoulish? Picking over the remains of an entire culture.”

“I’ve thought about that and come to this conclusion. Whether I visit it or not, it’s still going to be there. I can’t see how it’s any less respectful than watching the country sinking on the six o’clock news. At least this way it’s real.”

It was crowded inside the government building. Schools of slate grey fish with enlarged eyes, perfectly suited to the changed workplace environment.

It must have been crowded on that last night as well. Dozens of families sandwiched on the angled corrugated iron of the roof. I had a picture of Noah’s Ark in my nursery that looked like that when I was little; very wet and very crowded. Except in my picture there were no press helicopters circling above, nosey and useless like flying puppies. Or any refugees being airlifted in massive nets to the waiting flotilla.

We sat at home eating our dinner –lamb, as I recall- and watched as the storm surge lashed at the remaining families on the roof. It was like something out of Miss Saigon, only my mother didn’t cry as much as when we saw that in London.

Above me I can see sunlight pooling on the surface. I inflate my buoyancy vest a little and ascend beside the staircase, aiming for the gap in the rubble of the third floor. Grabbing hold of a rusted banister I pull myself over the stairs and onto the third floor. It is a wasteland of twisted corrugated iron and fallen brickwork, all covered in the same green buzz cut. One and a half walls remain. I can still see glass in a couple of the windows. Here, here is where it happened. I let all the air out of my vest and stand upright in the rubble. My head is about two metres below the surface. The last Tuvaluan was lifted from here. Now it is just me and the sharks. Three of them. Four. One by one they swim up to me, turning left or right at the last minute. Each one makes long eye contact with me as it swims by. That’s a weird feeling, but I’m not that scared. I’m trying to have a moment. This is what I came looking for.

Way out beyond the half wall was where the flotilla of US, Australian and New Zealand ships waited for that last Tuvaluan. Once he –a schoolteacher, I think- was in the net, Tuvalu got its final farewell. Three outriggers, attached by long lines to the rescue boats so as not to get blown away, bobbed above the island. You could still see the tops of some coconut palms between the swell. I guess our dive boat is tied up to one of them right now. Onboard each outrigger, dressed in ceremonial garb, were three men. Two with burning torches and one with a conch shell. Each outrigger raised their shells in unison and let out a long dirge for Tuvalu. At the dinner table I let out an involuntary “oh” when I heard it. I wonder if Atlantis had that kind of send off?

Then it happened. The Time Life Photograph of the Year. It was a telephoto from one of the press copters but the sound was captured by a tv crew on a nearby dinghy. Have you ever heard the sound of a man breaking down through a conch shell? You can listen to it on the web but it’s probably not the same.

Then it happened. The Time Life Photograph of the Year. It was a telephoto from one of the press copters but the sound was captured by a tv crew on a nearby dinghy. Have you ever heard the sound of a man breaking down through a conch shell? You can listen to it on the web but it’s probably not the same.

He was in the outrigger closest to the tv crew and he collapsed to his knees, one hand held up to his weeping eyes. (That was the Time Life photo. You could see the tops of some coconut palms and a wave crashing against the corrugated iron roof in the background. It was good.)

I think about that man now as I watch the sharks swimming around his home, swimming just a few feet from me. Would he want to see this? Would the sharks upset him so that he cried again or would they give him peace of mind at the thought that something still lives here? They have come here to see if there is anything left.

I can relate to that.