- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

(Nov 2004) A Day in Ramallah |

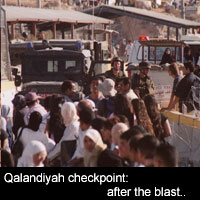

I was in the lobby of a hotel in Ramallah when I learned that a bomb had been detonated at the Qalandiyah checkpoint at the northern entrance to Jerusalem.

Peering out the window across the street, I could see my two American friends walking towards me. It was 4 o'clock; they were right on time.

Amjad and Majid Shehade were brothers - American Palestinians here on holiday to see old friends. I had met Majid the night before in the bar of the Jerusalem Hotel, where we agreed to share a taxi to Ramallah the next day.

This was the first bomb attack in greater Jerusalem for six months and early reports suggested that a number of people had been killed and dozens of others were injured. In response to the attack, the Israelis closed the checkpoint, and no one was being let in or out of the city. And 'no', Amjad and Majid hadn't heard.

The brothers had just lunched with Ayid (not his real name), a journalist friend and former employee of the Palestinian Authority. He was a good contact, and one who would prove vital in getting us back to Jerusalem in one piece.

Ayid told us that an Israeli military response was a strong possibility and things would become unsafe in Ramallah, so we had to get out of the city as soon as possible.

A few phone calls later, Ayid told us that Palestinian militants had set off a bomb at the checkpoint, killing two civilian bystanders and injuring up to a 18 others. Six of the injured were Israeli soldiers -the intended target. Qalandiyah was now closed, and may not re-open. He said he had to track down a taxi with 'Israeli' -rather than 'Palestinian'- number plates. It was our best chance of returning to Jerusalem.

The blast happened at 3pm, less than two hours after we had passed through. We knew that most vehicles with Israeli 'plates' would have left immediately following the bombing, so we had to get moving.

In the centre of town when Ayid wasn't talking on his mobile phone, he was probing every shop owner and taxi driver that crossed our path for information. I couldn't help imagining what I would have done if I had been alone -probably checked into the nearest hotel and prayed that the Israelis didn't launch a counter-attack. Having worked on stories like this in London, I knew how brutal this response could be.

Half an hour later Majid, Amjad and I were making nervous chit-chat. The clock was against us, but Ayid needed time to think. He took us to an internet café owned by a 'friend' and told us to occupy ourselves while he tried to formulate a plan.

Who on earth would I write to and what would I say? I began typing a vague message about where I was to the few 'current' addresses I still had in an email account that had lain virtually dormant for the past three years.

Rewind three hours -Amjad, Majid and I were seated together in a taxi on our way to Ramallah. They had a lunch appointment with their old 'friend', and I was going to try to meet President Yasser Arafat. It may sound like an overzealous ambition, but with a press-card in hand I knew that my chances were good. Journalists are permitted into the bomb-scarred compound which houses the Palestinian Authority to be briefed on the day's events, sometimes by Arafat himself. And the Palestinian leader loves talking to the press.

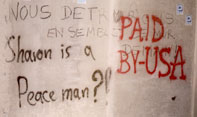

On the road to Qalandiyah we passed a partially constructed section of Israel's 'Separation Fence'. I had seen the barrier in Abu Dis and Bethlehem the day before covered with graffiti branding Ariel Sharon and George Bush war criminals. It was an abhorrent eyesore. When the 9m high structure is complete, it will meander for 725km through the West Bank, sometimes cutting indiscriminately through Palestinian farmland, helping the Israelis to tighten their stranglehold of the Palestinians homes.

Over a third of the barrier is now complete, and the Israelis claim it is the only immediate way to stop militants from killing Israeli civilians. But the United Nations disagrees -it says the wall is a direct violation of human rights. Earlier this year 150 countries voted to ban Israel from building the wall, five voted for it (including the US and Israel), and 10 countries abstained. Yet, backed by American support, construction goes on.

With only a few hundred metres left before we reached the Qalandiyah checkpoint we paid our driver and set off on foot. This is normal for cities in the West Bank, where you leave a taxi on one side of the checkpoint, and hope to find a new driver on the other side.

The checkpoint itself was an interesting sight, with a constant stream of people walking in both directions. The street was lined with vendors selling tea, household goods, groceries and sweets. Around a dozen Israeli soldiers, some of which looked as if they had barely graduated from high school, stood nervously clutching their weapons.

We passed through without having to show our passports -getting into a place like Ramallah was easy- it's getting out that is the difficult part. We found a driver and were on our way. Having arrived in the centre of town, we decided on a meeting point and set out on our respective journeys.

Clutching a tourist map that looked more like a cartoon-sketch of 'Springfield' than an actual city, I guessed it was only 2km to Arafat's compound. With a quick stop to grab a Schwarma to keep me going, I was on my way.

The compound was in worse condition than I had expected. After the heavy bombing it sustained at the hands of the Israeli military around two years ago, the majority of its buildings were severely damaged, or reduced to rubble.

I was stopped at the main gate by two young Palestinian soldiers who laughed among themselves as they checked my passport and press'card, before asking me what I was doing in Ramallah and why I wanted to visit the Palestinian Authority. I had a scripted answer prepared.

'I am here to report on the day's events and am hoping to meet President Arafat.'

'Ok. No photographs.'

'Sure,' I replied. It had worked and I was in.

Walking up the rocky driveway I surveyed the inside of the compound. How could this be the Palestinian Authority's headquarters? Buildings were literally cut in half by Israeli mortar fire and air strikes. Lounge rooms, kitchens and bedrooms were completely exposed and resembled a sorry exhibit in an Ikea showroom.

Despite the wreckage, the Palestinian guards stood proud and alert as they patrolled the grounds. Trying my best not to stare at, what I imagined, was once a competent collection of government buildings, I headed for a newly painted iron gate that I took to be the entrance to Arafat's home and the PA's offices. It was the only building I could see on the large grounds that was still intact. I knocked on the door. Seconds later, a small latch opened and a pair of eyes peered through the bars. I repeated the scripted answer I had used so effectively on the guards at the main gate.

Despite the wreckage, the Palestinian guards stood proud and alert as they patrolled the grounds. Trying my best not to stare at, what I imagined, was once a competent collection of government buildings, I headed for a newly painted iron gate that I took to be the entrance to Arafat's home and the PA's offices. It was the only building I could see on the large grounds that was still intact. I knocked on the door. Seconds later, a small latch opened and a pair of eyes peered through the bars. I repeated the scripted answer I had used so effectively on the guards at the main gate.

But the penetrating gaze gave no response.

'I'm here to cover the day's events,' I said. 'Is President Arafat speaking today?'

'No press today!'

I knocked again. The latch slid open.

'There will be no press today, go!'

I tried a few more lines, but it was no use. The Palestinian Authority was, indeed, not letting journalists in this day, and that included me. So, defeated, I headed back into town.

Back in the internet café, I had just sent my email when Ayid signalled it was time to go. I quickly gathered my things, and seconds later we were saying goodbye to him and were in a taxi heading for the scene of the blast.

'Why are we going there?' I asked.

'We have to try this first, it could have re-opened,' Amjad replied.

It was near-pandemonium when we got there. Hundreds of Palestinians had gathered and were screaming at the heavily armed Israeli guards, who had now doubled in number and were lined across the road behind a series of concrete barricades. Ambulances were treating the last of the injured, and television news crews were set up all over the place reporting on what had just happened.

Amjad and I got out of the car and walked closer to the checkpoint to get a better look. Meandering through the crowd, we both agreed that it was not going to open for a long time.

We desperately needed a plan B, and as our driver sped off towards the outskirts of Ramallah, it appeared that he already had one. Amjad spoke to him in Arabic and explained to me that there was another checkpoint set up especially for the Israeli military and United Nations. With our passports, he said there was a strong chance we would be let through.

We drove for at least 20 minutes, most of it in silence. As the houses and buildings began to disappear, I suspected we were getting closer to our back-up plan.

The brothers were laughing at something our driver was saying. I found out later the crux of the joke.

'You haven't seen anything yet,' he had told them, referring to our predicament.

He said that Palestinians were often left stranded outside West Bank towns and cities they called home, but often, they found a way to defy the checkpoints. Around two years earlier our nameless driver was stuck outside Ramallah for days, but determined to get home, he and a group of others headed 'off'road' into the desert in search of another route. It took them almost 24-hours to get home undetected, and at times they had to physically carry their vehicle when the road was impossible to navigate, across rocky paths and sandy tracks. So according to him, we were lucky.

Their laughter quickly subsided when a barrier appeared in the middle of the dirt road. Our driver stopped. To our left was a large complex which turned out to be a military prison. We were on the edge of a small hill, and below, a thin sandy track ran stretched out to a small military outpost.

'This is it,' he said, gesturing towards the outpost surrounded by a couple of military vehicles and half a dozen soldiers sitting lazily in the sun.

'But you will have to walk from here,' our driver said.

I had a small backpack, and so did the boys. We agreed that it was not a good idea for us to approach a checkpoint carrying anything, especially a bag of any kind as the bomb at Qalandiyah was packed in a small bag and left by the side of the road before it was detonated by mobile telephone.

I had a 'press-pass', and Amjad looked much less Palestinian than his brother, so we decided that the two of us would walk down and talk to the guards in person, and tell them that our friend would be following us with our bags when we were given the 'all-clear' to cross.

So, with arms outstretched and passports in hand, we walked the 500m to the checkpoint. Arriving to a string of aggressive stares, we explained that we had chosen this checkpoint because we were foreigners and needed to get back to Jerusalem that night. They checked our passports, and said they would allow us to pass through.

We telephoned Majid, and minutes later he was struggling down the dirt track, hot and sweaty, with our bags. They interrogated him for what felt like an hour, but was in actual fact only a few minutes, while Amjad and I did our best to look patient. Eventually, they handed him his passport and bid us farewell.

We barely spoke as we hurriedly walked away from the checkpoint. And as we stood in the searing heat by the side of the freeway in the middle of nowhere waiting for a taxi, we had to laugh. As we had been told, things could have been a hell of a lot worse.

When not dodging mortar attacks, Tim is a journalist based in London.

*This article first appeared in the debut issue of The Cud in November 2004.