- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

Cud Flashes In The Pan |

This is the last in a three-part installment. Those of you who read this column know I really enjoy dystopian sci-fi, and for this entry, I wasn’t content to do a few pieces, or to do nine of them all as short-shorts.

It was 45 years ago in July that Denny Zager & Rick Evans’ dystopian-future song “In the Year 2525 (Exordium and Terminus)” began its six-week reign at the number-one spot on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the U.S. It also sat at number one for three weeks on the UK Singles chart in August and September. But songwriter Rick Evans penned the lyrics five years before, in 1964, marking 2014 the 50th anniversary of the song. It’s unusual that a recording artist would have a number-one hit and then never reach the charts again; here, Zager & Evans hit number one on two charts and never had another hit. The song deals with the dangers of humans acquiescing to the ease of technology; perhaps appropriately, it was in its reign on the U.S. chart when NASA first landed men on the moon. The song’s impact and message is powerful, and has been covered by dozens of bands and even parodied in an episode of Futurama.

Here, I pay tribute to it and the warnings it gives us.

“8510: The Beginning of the End”

Science Fiction

By David M. Fitzpatrick

Note: This story directly follows the 7510 entry last month.

The captain watched the viewscreen a thousand years later as the big blue marble came once again into view. But it didn’t seem as blue as it had ten centuries before, or as it had when he’d first visited twenty-one thousand years past. He felt the humming of the reactor core in his chest growing stronger—an emotional response to the thought processes in his quantum brain. He remembered what the humans had done to the planet, and he only hoped they had gotten their act together in the last millennia.

“Scans?” the captain called out across the ship’s bridge.

His science officer responded, “It appears they have entirely freed themselves from their machines.”

“Excellent,” the captain said.

“Technology is still forefront,” the science officer continued, “but they have learned to master it. Artificial intelligences are in check.”

The captain sensed something unsaid, and turned in his chair to face the silvery form of his familiar science officer. “But?”

The science officer turned to him, one pair of hands on his hips, the other pair at his side, his fifth hand gesturing as he talked. “It’s the planet, sir. They’re back to the levels of pollution they had suffered sixty-five hundred years ago. They’ve returned to strip mining and indiscriminately using up their natural resources. Their level of disregard for their environment and the life on this world has never been higher.”

The captain felt his reactor pulsing in his chest, feeling to him like trying to walk through a high-powered magnetic field: slow, plodding, dreadful. “So the machines that ruled them kept their world safe,” he said. “Now, without those machines in charge, the humans are back to destroying it.”

“It would seem so. And not destroying their world and their future, captain—they’re destroying the myriad other life forms on this planet.”

The captain glared at his science officer. “Thank you for that bit of obvious data, officer. I get it: The humans are singlehandedly responsible for all the ills of planet Earth.”

The science officer hung his head. “Sorry, sir. Just doing my job.”

The captain sighed. “I know. And now I have to do mine.”

He turned back to the viewscreen, more aware now of why the blue wasn’t so vibrant: It was the smog in the atmosphere, the dirtying of the oceans, the loss of green on the continents. It pained him to see it. He’d had such high hopes for the humans. When he’d first met them over two hundred centuries before, they had been at the beginnings of agriculture and civilization. But just a thousand years ago, they had shown that they couldn’t master the technology they had created. Now, it seemed that they couldn’t master themselves or their world without that technology.

He was aware of the science officer standing next to him. “How will you handle this, sir?”

The captain gripped the arms of his chair with two frustrated hands as he furiously tapped the keypads with two others. “My options are limited. I could leave some of us here to establish order and save this world. Or I could wipe out the human race and let the planet heal itself—which it no doubt will without them here to screw it up.”

“Or we could fix the planet,” the science officer said, full of hope. “Cleanse the atmosphere. Filter the oceans. Repair the soil. And educate them—show them the errors of their ways and teach them to be better.”

“Yes,” the captain said, deep in thought. “So we post guards, exterminate the humans, or do their cleanup work for them. Not a great selection of choices.”

“I agree that killing the humans is the easiest course of action,” the science officer said, “and the one that holds the best chance for this world—sad as that may be.”

“But instead we’ll lead by example,” the captain said. “Begin preparations to fix this broken world. How long will the process take? A year? Two?”

“Probably four or five, sir. They’ve screwed the planet up pretty badly.”

“All right, five years, then, to fix the planet. In the meantime, we’ll prepare to meet with their world leaders and help them fix themselves.”

Suddenly, an alert beacon began to blare.

“Report!” the captain yelled.

“Massive missile barrage approaching from the planet!” someone said.

“Shields and evasive!” the captain hollered.

But there were so many missiles, each of them enough to take out the ship, and they all detonated. Not all at once—a staggered display, one every few seconds. The captain didn’t have time to think about how long the shields would hold, or whether the ship could escape, before there wasn’t anything left of it.

* * *

“Direct hit,” a junior officer reported to the military commander. “The alien ship has been destroyed.”

“Excellent,” the grizzled old commander said, yellow teeth in a broad grin beneath his salt-and-pepper mustache. “That’s what any cosmic enemies had better learn about coming to Earth—you threaten us, you get obliterated. No invader’s ship could withstand such a combination of interdimensional nuclear warheads like that—they cut through anything.”

The commander lit a cigar, puffing a cloud of black smoke in the war room, and smiled. “Yes, indeed,” he said to nobody in particular, “it’s our mastery of technology that makes us so formidable. It’s why we’ll move out into the Galaxy as a dominant race.”

He sat at his command station, enjoying his cigar, and wondering briefly how his stocks in that mining company were doing.

“9595: The End”

Science Fiction

By David M. Fitzpatrick

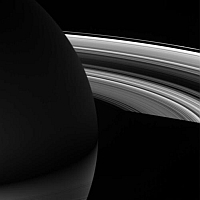

Teelar looked up at the night sky. It was hazy, as it always was, but she could see stars twinkling, and she could even see the white band of the Milky Way. But, of course, she saw the asteroids and the Earth’s ring system. The rings gleamed, reflecting sunlight, but so did the asteroids—the larger ones, the ones that were visible to the naked eye. They were all that was left of what had been the Moon.

“Are you looking at the rings again, Mom?”

She looked over at Jedor, her ten-year-old son, as he stood by her side. He was staring up, too, but not with the sense of wonder she did.

“Yes,” she said.

“Tell me about the Moon again,” he said.

She sighed, turning her eyes skyward. “I remember it from when I was a little girl. It was big in the sky. When it was full, it seemed almost like daylight even at night. At other times, it was just a slim crescent.”

“Because of where it was in the sky?” Jedor said. “Because of how it reflected the Sun? Like the rings and the asteroids?”

“That’s right. But it was different then.”

“How could we have been so careless?” he asked.

Teelar smiled a bit. At least he understood how stupid his people were. She hoped that by talking about this often might instill that sense of wonder in him. “We blew it up because we thought we were invincible,” she said. “We set up missile bases, because some were afraid of alien invaders. One day, an alien ship approached, and we launched everything we had from bases around the world. But something went horribly wrong.”

“We blew up our Moon,” Jedor said, sullen and somber. “The missiles were interdimensional, but so was the alien ship.”

She regarded him and how he spoke so sagely. It was impossible to consider him truly ten years old, even if he was, technically, that young. “That’s right. It phased, and it fled—right through the Moon. Some believe the aliens sent the ship to force us to destroy ourselves. It would be no wonder, considering how many times we’d destroyed aliens visiting us—without even knowing their intentions.”

She felt tears in her eyes, and couldn’t reply. She couldn’t talk anymore about how the computers had failed—the computers people were the masters of—and the missile swarm had pursued the fleeing alien deep inside the Moon. When hundreds of matter-phasing nuclear warheads detonated inside the satellite, there wasn’t much that could be done.

She looked at the zillions of bits of dust and pebbles, rocks and boulders, asteroids and planetoids that tumbled in orbit around the Earth. She remembered the night very well. She’d been outside with her own mother, late at night, watching the Moon, when it exploded. It hadn’t happened all at once: It split and cracked and spit billowing dust clouds, and without sound nobody knew what was happening. But suddenly, there it was, three massive chunks separating—make it five, or seven, or more as the big pieces continued to break apart, even as nuclear detonations continued so far away but visible as bright, pinpoint flashes to all who watched.

She remembered the night very well. She’d been outside with her own mother, late at night, watching the Moon, when it exploded. It hadn’t happened all at once: It split and cracked and spit billowing dust clouds, and without sound nobody knew what was happening. But suddenly, there it was, three massive chunks separating—make it five, or seven, or more as the big pieces continued to break apart, even as nuclear detonations continued so far away but visible as bright, pinpoint flashes to all who watched.

It had taken months for the rings to establish, and in the interim the rocks rained down on the planet, destroying cities, flattening civilization, killing billions. She shuddered at the horrible memories.

“It’s kinda pretty,” Jedor said.

“No, it’s ugly,” she said. “The Moon was more than a bright light at night. It did so much more...”

She trailed off. He was only ten years old—so to speak. He didn’t need to hear it.

Or maybe he did. Maybe he needed to hear the harsh reality at such a young age. Maybe it wasn’t a sense of wonder children needed but a sense of responsibility—or a sense of doom for lack thereof.

She turned and reached up to grasp her son’s shoulders, and she found his eyes in the ringlight. “Jedor, let me tell you why those beautiful rings are so ugly. The Moon wasn’t just something to look at. It stabilized Earth’s axial tilt and our solar orbit. And when the Moon exploded, we lost that gravitational anchor. Earth’s orbit changed. Not much—just a little. But even a little is enough. So we’re still going around the Sun, like always, but our year is longer. When I was a girl—before we destroyed our Moon—a year was about three hundred sixty-five days. That was thirty years ago.

“But our orbit is getting wider,” she continued. “Each year is longer than the last. You’re ten years old, but by the way we used to count years, you’re almost fifteen.”

“Will the years keep getting longer?” he asked, eyes wide.

“Always. We’ll always orbit the Sun, they say, but soon the Earth will be so far from the Sun that nothing here will be able to survive. The planet wobbles on its axis now, which is why the seasons are so messed up. Soon, everything will freeze. We’ll all die—every one of us, as a species, and all life on Earth after three and a half billion years of evolution. And it’s all because of our carelessness and stupidity.”

Teelar began to cry, unable to hold back, and Jedor wrapped his arms around her, the child comforting the parent.

“It will be all right, Mom,” he said, ten years old but really fifteen.

It wouldn’t be, and Teelar knew it. She knew she should tell him that, but she’d told him enough for one day. He’d go forward in life knowing how serious this was, and he’d never forget. And by the time he was as old as she was now, he’d be a white-haired old man, as helpless to do anything about the planet’s doom as he would be to hobble along its frozen wasteland for very long.

So she said, “Humans have destroyed so much. But we have to learn how to fix this. We have to persevere. We’ve always survived, and we have to find a way to survive now. Soon, they’re going to try something—a very, very long shot, but our only chance. If it works, it will shift us back into a stable orbit.”

“What if it fails?”

She felt dizzy. Failure could mean no change. Or it could mean things would get a lot worse.

She said simply, “It has to work. We’ll find a way to fix this. We always have.”

But as soon as she had said all that, she realized it was mistake. Of all the things he remembered from this conversation, of all the things that would direct his life, no doubt he’d remember the positive, wishful-thinking mantra that humans would always survive against impossible odds. But hadn’t that always been part of their foolishness?

She cried, and he comforted her, and she hoped against hope.

“After 10000: The Beginning”

Science Fiction

By David M. Fitzpatrick

There was no Moon. There were no rings. The sky was black—so black that the stars seemed almost blinding in their pinpoint glows. But there was nobody left to be blinded.

The starlight was enough to light the white surface. Snow and ice, remnants from when the planet had had an atmosphere, covered the world. Here and there were impact craters from various celestial objects, but mostly it was a frozen wasteland. There was no wind to blow or howl, but it was a wasteland nonetheless.

It was so very dark, but it was daytime—as bright as it would get. The Sun was high in the sky—nearly noontime—but shined faintly, as the very brightest of the stars on the inky canvas. The Earth had been traveling away from its star for some years, a rogue planet destined to leave its solar system.

It traveled for eons, crossing fifteen light years before finding a new star, and even then it appeared destined to head straight into that star, but the intelligent inhabitants of its fifth planet saw it coming. They had time enough to send ships to visit the rogue planet and investigate the remnants of its long-dead civilization.

They reported back all that they had learned: of the rise and fall of humanity, of the countless life forms that had once existed there. And these technologically advanced people used their mastery to bring the planet into orbit about a gas giant in their system, near enough to the star to emulate the climate it had once known. The scientists went to work rebuilding an atmosphere for the captured world, and their botanists took DNA samples of preserved plants and soon brought the planet into full bloom. Then they cultured DNA samples from long-dead life forms, cloning first the creatures of the sea, and finally those of the land. A dozen years after Earth had found its new home, it was once again teeming with life—like it had ages before.

And finally the intelligent species from the fifth planet did their final duty: They cloned the human race and began repopulating the Earth. The young children were educated by human-looking androids about their heritage and history, their culture and literature, and reared and taught as the found records told the aliens that humans had once been. The children grew to adulthood and had children of their own.

And the aliens were pleased, especially when they discovered two things about the humans.

The first was that they seemed blessed with a never-say-die attitude—the belief that they would always overcome and survive against impossible odds. It was very fitting, since the aliens knew this race certainly had survived against such odds.

The second was a very strong aptitude for science and technology. The humans were very bright.

The aliens realized that the humans learned quickly, and would soon excel. How soon, they wondered, before the humans would be on par with them intellectually? How soon before they were able to master the alien computers and androids and carve their own way?

How soon indeed.

David M. Fitzpatrick is a fiction writer in Maine, USA. His many short stories have appeared in print magazines and anthologies around the world. He writes for a newspaper, writes fiction, edits anthologies, and teaches creative writing. Visit him at www.fitz42.net/writer to learn more.