- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

The Cud On Film: Three Classic Takes On Fascism — Roma, Citta Aperta, Il Conformista, and Lacombe, Lucien |

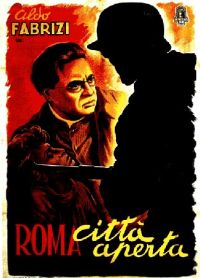

As a traditional Neo-Realist film, in Roma, Citta Aperta (1945) director Roberto Rossellini  attempted to provide an account of resistance fighters in Italy that was free from the propaganda and censorship of the fascist cinema. In 1952 he stated that Neo-Realism was “a response to the genuine need to see men for what they are, with humility and without recourse to fabricating the exceptional; it means the awareness that the exceptional is arrived at through the investigation of reality.”

attempted to provide an account of resistance fighters in Italy that was free from the propaganda and censorship of the fascist cinema. In 1952 he stated that Neo-Realism was “a response to the genuine need to see men for what they are, with humility and without recourse to fabricating the exceptional; it means the awareness that the exceptional is arrived at through the investigation of reality.”

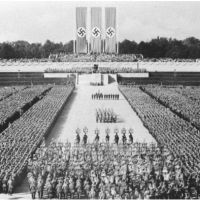

In line with this objective, in his film Rossellini portrayed the vast majority of Italians as having little political commitment or dedication towards the German Nazis, and instead remained impartial, or as he depicted, helped the resistance movement. Even the Italian fascists under the control of the Germans are presented in a reasonably favorable light, and the only ‘evil’ characters as such are shown to be the Germans themselves and in particular the S.S and Gestapo. During the course of the film the Nazis employ various means such as torture, >murder, and the use of drugs to achieve their aims, and Rossellini even suggests the Nazis to be sexually deviant by way of a lesbian Gestapo agent. The Germans are depicted to have an almost blind faith and political commitment to Nazism that comfortably sat alongside murder and other morally reprehensible behavior.

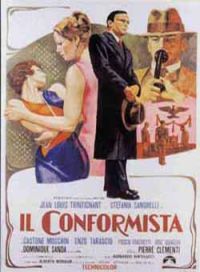

In Bernardo Bertolucci’s Il Conformista (1971), he asks direct, fundamental questions about what type of person becomes a fascist, and what draws them into the ideology. Though Bertolucci carries throughout his film the image of fascists as brutal, sexually perverse thugs, he also shows that not all members of the movement joined because of any type of passionate political commitment, and this is especially true in his leading character, Marcello Clerici.

In Bernardo Bertolucci’s Il Conformista (1971), he asks direct, fundamental questions about what type of person becomes a fascist, and what draws them into the ideology. Though Bertolucci carries throughout his film the image of fascists as brutal, sexually perverse thugs, he also shows that not all members of the movement joined because of any type of passionate political commitment, and this is especially true in his leading character, Marcello Clerici.

While perhaps not a historically accurate representation of fact, Bertolucci depicts the fascists of Italy as having confused, distorted perceptions of the world. In their search for what the author of Il Conformista, Alberto Moravia called ‘normality’ they were drawn into the political movement. Marcello similarly comes from a very unstable background. Sexually abused as a child, he also has an extremely dysfunctional family consisting of an insane fascist father, and a promiscuous, decadent mother addicted to morphine. He has the additional guilt of having murdered his abuser, Lino, and also the confusion of his own sexuality, which at the film’s end we presume to be homosexuality.

With such an unstable and irregular past, Marcello joins the Fascists to try and restore some balance to his life. Soon after, he marries and has a child. Just like all of Bertolucci’s fascists, Marcello is, as the film’s title  suggests, merely conforming to fascist values and beliefs in order to stabilize his life and attain a sense of identity. At no time is Marcello seriously committed to fascist political ideology, and this is most apparent at the end of the film when, with fascism defeated, he is liberated from the confines of the movement and reveals his homosexuality.

suggests, merely conforming to fascist values and beliefs in order to stabilize his life and attain a sense of identity. At no time is Marcello seriously committed to fascist political ideology, and this is most apparent at the end of the film when, with fascism defeated, he is liberated from the confines of the movement and reveals his homosexuality.

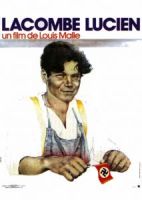

Lacombe, Lucien (1974) addresses similar themes but in the context of the French Vichy regime of the early 1940’s. Though several of the fascists are depicted as cruel or fanatically committed to their ideology and movement, the film directly challenges traditional views of all fascists as monsters. Director Louis Malle himself best explained the nature of his leading character Lucien as “a young peasant who might just as well have become a resister and who enters the service of the Gestapo by accident.”

In Malle’s film, his character Lucien comes from a boring and frustrating lifestyle, and a dissatisfying home life. Seeking adventure and change he approaches an individual known to be the leader of the local resistance movement, but is turned away. When, however, one night a punctured bicycle tire prevents him from getting home before the Vichy curfew, he  is arrested and taken to a large mansion used as a local headquarters for the fascists. There he experiences firsthand the wealth, luxury and power of the fascists, and accepts a chance offer to join and collaborate with the movement. Clearly, then, Lucien, lacking any political sentiments but seeking an outlet for his aggression, ambition, and a direction to his life, joins the movement as much due to accident and luck than any other particular factor.

is arrested and taken to a large mansion used as a local headquarters for the fascists. There he experiences firsthand the wealth, luxury and power of the fascists, and accepts a chance offer to join and collaborate with the movement. Clearly, then, Lucien, lacking any political sentiments but seeking an outlet for his aggression, ambition, and a direction to his life, joins the movement as much due to accident and luck than any other particular factor.

When love intervenes into Luciens’ world, he abandons fascism and escapes to the countryside with his lover, France (a Jew, and thus directly opposing fascist ideology), and her grandmother, even though just a few weeks before he was killing for the Gestapo. Although, as historian Paul Jankowski has offered, Malle’s film shocked the traditional mythology of fascism and the resistance, it is important in showing why many collaborated with the Fascists and Nazis, whether it was for money, power, by accident, or merely an of survival. What is most critical is that all of these reasons are disconnected from any type of true political commitment. While not necessarily representative of the majority experience, the reasons nonetheless merit examination.

Three classics of European cinema thus dealt with the subject of political commitment to fascism by varying approaches: In Roma, Citta Aperta, the Italian collaborators were portrayed in a fair light, and only the  German Nazis were depicted as evil and actmerciless. Il Conformista presented a similarly critical view of the fascists, but tried to show that many of its members were of an unstable nature, turning to the movement as a means of ‘fitting in’ and achieving normality. And in Lacombe, Lucien the traditional view of collaborators was shattered, suggesting that many individuals who had joined the movement did so merely for material or ambitious reasons, or even due to accident. The common thread through all three films, however? That political commitment was by no means a pre-requisite for membership to the Fascist or Nazi parties of World War Two.

German Nazis were depicted as evil and actmerciless. Il Conformista presented a similarly critical view of the fascists, but tried to show that many of its members were of an unstable nature, turning to the movement as a means of ‘fitting in’ and achieving normality. And in Lacombe, Lucien the traditional view of collaborators was shattered, suggesting that many individuals who had joined the movement did so merely for material or ambitious reasons, or even due to accident. The common thread through all three films, however? That political commitment was by no means a pre-requisite for membership to the Fascist or Nazi parties of World War Two.