- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

The Cud Essay: Garveyism and the UNIA in early 20th Century America |

In 1925 Marcus Mosiah Garvey wrote: "Let the sky and God be our limit, and Eternity our measurement.... Remember, we live, work and pray for the establishing of a great and binding RACIAL HIERARCHY, the founding of a RACIAL EMPIRE whose only natural, spiritual and political limits shall be God and Africa, at home and abroad."iIn little over a decade, but most particularly during his time in the United States, from 1916 to 1927, Jamaican born Garvey and his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) captivated the consciousness and interests of millions of blacks worldwide on such a scale as had never been witnessed before. In his formative years, working in his homeland of Jamaica, and also in Central and South America, and studying in England, Garvey became acutely aware of the terrible plight of the African race throughout the globe, and as a result set up the UNIA and the African Communities League (ACL) in 1914 to try and improve this.ii Reflecting on his career, he recalled: "I asked, 'Where is the black man's Government?' 'Where is his king and his kingdom?' 'Where is his President, his country, and his ambassador, his army, his navy, his men of big affairs?' I could not find them, and then I declared, 'I will help to make them.' "iii

In 1925 Marcus Mosiah Garvey wrote: "Let the sky and God be our limit, and Eternity our measurement.... Remember, we live, work and pray for the establishing of a great and binding RACIAL HIERARCHY, the founding of a RACIAL EMPIRE whose only natural, spiritual and political limits shall be God and Africa, at home and abroad."iIn little over a decade, but most particularly during his time in the United States, from 1916 to 1927, Jamaican born Garvey and his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) captivated the consciousness and interests of millions of blacks worldwide on such a scale as had never been witnessed before. In his formative years, working in his homeland of Jamaica, and also in Central and South America, and studying in England, Garvey became acutely aware of the terrible plight of the African race throughout the globe, and as a result set up the UNIA and the African Communities League (ACL) in 1914 to try and improve this.ii Reflecting on his career, he recalled: "I asked, 'Where is the black man's Government?' 'Where is his king and his kingdom?' 'Where is his President, his country, and his ambassador, his army, his navy, his men of big affairs?' I could not find them, and then I declared, 'I will help to make them.' "iii

By September 1921, Garvey's movement, based in Harlem, New York, claimed some six million members, and nearly nine hundred regional and international branches.iv The reasons for such a powerful post-World War One response (both from supporters and opponents) to Marcus Garvey and the UNIA are many and varied. In the historical context of the period, both locally and internationally, events such as the influx of African-Americans migrating north in the early twentieth century, the impact of the "betrayal" of World War One,v and the race riots which shook the United States in 1919 contributed to the growth of an already developing black nationalist consciousness, which was in many ways increasingly militant, and certainly receptive to the defiant and forthright ideals of Garveyism, preaching themes of race pride, economic self-determination, and espousing visions of a future black empire, founded in Africa. Garvey successfully merged elements of religion with the encouragement of a civilised black culture, with black utopianism, and with a doctrine of success, yet was able to support his dreams and visions of the future with material proof of black achievement.vi

Above all, Marcus Garvey and the UNIA represented the first cohesive and aggressive attempt to offer racial salvation to an audience that was increasingly disillusioned with the relative passivity and higher class concerns of other contemporary African-American interest groups, such as W.E.B. Du Bois' National Association for the Advancement of Coloured Peoples (NAACP), and the contradictions of an American government that preached liberty and democracy abroad, but practiced alternative policies domestically. As Martin Luther King commented in a 1965 speech, "He was the first man on a mass scale and level to give millions of Negroes a sense of dignity and destiny, and make the Negro feel that he is somebody....",vii and indeed he articulated a kind of black nationalism such as was not to be seen again until the emergence of the Black Panther party in the 1960's.viii

Above all, Marcus Garvey and the UNIA represented the first cohesive and aggressive attempt to offer racial salvation to an audience that was increasingly disillusioned with the relative passivity and higher class concerns of other contemporary African-American interest groups, such as W.E.B. Du Bois' National Association for the Advancement of Coloured Peoples (NAACP), and the contradictions of an American government that preached liberty and democracy abroad, but practiced alternative policies domestically. As Martin Luther King commented in a 1965 speech, "He was the first man on a mass scale and level to give millions of Negroes a sense of dignity and destiny, and make the Negro feel that he is somebody....",vii and indeed he articulated a kind of black nationalism such as was not to be seen again until the emergence of the Black Panther party in the 1960's.viii

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were particularly marked by the migration of African-Americans to the cities.ix This migration was largely due to the oppressive racism and poor agricultural conditions of the South, and the impact of the industrial boom of World War One upon the labour market, which made possible the conditions needed for increased black migration north.x Many African-American migrants also held the hopeful but ultimately unrealistic beliefs that a better lifestyle could be found in the north, with more jobs, higher wages, better educational opportunities, better policing and improved standards of living. Others dreamt that the north would be a region of racial equality far removed from the harsh South.xi

World War One, in particular, offered the very real (and not unjustified) hope that victory would herald widespread changes in the condition and treatment of African-Americans due to the significant propaganda and ideological justifications of the conflict, as a fight for liberty and the freedom of all people.xii African-Americans generally responded loyally to the conflict, as nearly 400,000 men served in the armed forces, and more than $250,000,000 worth of bonds were raised for the war effort.xiii

World War One, in particular, offered the very real (and not unjustified) hope that victory would herald widespread changes in the condition and treatment of African-Americans due to the significant propaganda and ideological justifications of the conflict, as a fight for liberty and the freedom of all people.xii African-Americans generally responded loyally to the conflict, as nearly 400,000 men served in the armed forces, and more than $250,000,000 worth of bonds were raised for the war effort.xiii

The sum result of such expectations was that blacks looked increasingly for a kind of "second emancipation" in the early part of the twentieth century, and when this did not emerge, disillusion, hardship and disappointment set in, particularly in the absence of any solid and sufficiently aggressive black leadership in the aftermath of Booker T. Washington's death in 1915.xiv African-Americans in the north found unsatisfactory living conditions and bitter competition in the workplace, and as E. David Cronon has offered on the subject, these new Negroes of the north found that they were still only second-class citizens, "...the last to be hired and the first to be fired."xvMany returning African-American soldiers, disappointed by the results of the Versailles Peace Conference and the failure of the new League of Nations to adequately address the interests of the African races, xvi and yet encouraged and emboldened by their experiences in "freer" countries abroad, were no longer prepared to accept the inequalities of pre-war United States, and several now asserted their willingness to fight, if necessary, to gain such rights as they felt they justly deserved.xvii The mounting racial tensions of the period were not only represented in the re-emergence of the Ku Klux Klan,xviii but also in the outbreak of several bloody race riots from 1917 to 1919 (twenty six in the so-called "Red Summer" of 1919), often sparked on occasion by open confrontations between returning soldiers and white civilians, or black and white co-workers.xix Clearly, from the late nineteenth century to the years immediately after World War One, a new black consciousness was cultivated, founded upon these experiences of hardship and disenchantment, but which was increasingly seeking more radical solutions to the problem of race in the United States.xx

Considering the evolution and nature of this black consciousness, awaiting mobilisation in the ghettos of the north, awaiting a "Black Moses",xxi it is not surprising that Garvey was able to secure a broad base of supporters (though startlingly quickly), beginning in Harlem, where the first UNIA chapter was established in 1917. Harlem, with its significant African-American population, was highly politicised and home for many radicals of all types- a strong site for a movement such as the UNIA.xxii The appeal of Garveyism and the reasons for the success of the individual and his movement and the considerable response he evoked are encapsulated in his ideology, as expressed in his many speeches, articles and especially in the lessons he designed for his 1937 School of African Philosophy, but also in his material and physical proofs of success.

Considering the evolution and nature of this black consciousness, awaiting mobilisation in the ghettos of the north, awaiting a "Black Moses",xxi it is not surprising that Garvey was able to secure a broad base of supporters (though startlingly quickly), beginning in Harlem, where the first UNIA chapter was established in 1917. Harlem, with its significant African-American population, was highly politicised and home for many radicals of all types- a strong site for a movement such as the UNIA.xxii The appeal of Garveyism and the reasons for the success of the individual and his movement and the considerable response he evoked are encapsulated in his ideology, as expressed in his many speeches, articles and especially in the lessons he designed for his 1937 School of African Philosophy, but also in his material and physical proofs of success.

The ideology of Marcus Garvey and the UNIA contained many elements, several of which were strongly interrelated. Inherent to the ideological basis of Garveyism were the doctrines of success and racial pride. Garvey never hesitated to openly criticise what he saw to be failings within the African races.xxiii His grievance in March 1921 was typical of his general belief: "We are believing that we are still too humble to soar to the heights of independence and freedom and liberty."xxiv Indeed, Garvey further asserted that "There are two classes of men in this world, those who succeed and those who do not succeed",xxv and he could see no clear reason (other than failure on the part of his own people) why African-Americans could not and should not succeed in business, politics, and other ventures just as whites had.xxviGarvey equated individual success with success of the race, and argued that only through greater individual achievement would civil rights and opportunities be more readily granted.xxvii

Garvey's emphasis upon economic self-determination for African-Americans was central to this success doctrine: "We believe that the Negro cannot succeed on sentiment or emotion..." he stated. "We must succeed in business."xxviii Several of these ideals were later expressed in the lessons taught in Garvey's School of African Philosophy. The lessons, based upon the principles of "New Thought",xxix included titles on "Intelligence, Universal Knowledge and How to Get It", "Leadership", "Elocution", "Character", "Diplomacy", and "Personality"xxx In his lessons on "Economy" and "Commercial and Industrial Transactions", Garvey encouraged wise investment and the entrepreneurial business spirit, but discouraged giving money away outside of one's race since it would eventually contribute to the erosion of the economy, commerce and industry of the African-American race.xxxi Above all, Garvey stressed that Negroes should help each other financially where possible, since the rise and fall of one person's fortunes might equate to the rise or fall of the entire race, and he drew on the financial successes of other races as examples of the level of achievement that had to be aimed for.xxxii

As Garvey's lessons on "God" and "Jesus Christ" also reveal,xxxiiireligion was important to the ideology of the UNIA. On one level, Garvey emphasised the right of all African-Americans to assert themselves as Christians,xxxiv and to interpret the scriptures as God himself (and not white racists) would have interpreted them.xxxv Further, Garvey expressed that God was neither white nor black, but that "...if they say that God is white, this organisation says that God is black; if they are going to make the angels beautiful white peaches from Georgia, we are going to make them beautiful black peaches from Africa."xxxvi

As Garvey's lessons on "God" and "Jesus Christ" also reveal,xxxiiireligion was important to the ideology of the UNIA. On one level, Garvey emphasised the right of all African-Americans to assert themselves as Christians,xxxiv and to interpret the scriptures as God himself (and not white racists) would have interpreted them.xxxv Further, Garvey expressed that God was neither white nor black, but that "...if they say that God is white, this organisation says that God is black; if they are going to make the angels beautiful white peaches from Georgia, we are going to make them beautiful black peaches from Africa."xxxvi

Such expressions therefore tied religion on another level to the ideology of black nationalism and the aforementioned doctrine of success, and what several commentators have described as the creation of the "Black civil religion" of Garveyism”.xxxvii Marcus Garvey spoke in a religious and Biblical tone, for instance, when he expounded that "The Negro now or at some time will have to give his martyrs or offer his sacrifice before the race can be redeemed."xxxviii That is, Garvey's movement used religion in many respects as a means of justifying his ideology, and as a part of this process Garvey became the manifestation of the mythology of racial messianism in America for a large number of his supporters.xxxix This merging of religion with the political was of considerable appeal to the black consciousness of the period, and Garvey's care not to outwardly accept any single Christian denomination over others helped to retain a UNIA membership from a broad spectrum of society and beliefs, and increased the co-operation of the clergy with the movement.xl

Consistent with the aims and objectives of the UNIA was the role of Africa as the motherland of all Negroes. Marcus Garvey attempted to present Africa as a country with a great historical heritage to be acknowledged and proud of, and which, as the "natural home of the race", would eventually be re-settled as a part of the UNIA "Back to Africa" movement, and thus re-claimed from the oppressive colonial powers of Europe.xli Upon this, Garvey hoped that the African races of the world, in the spirit of co-operation and confraternity, would enter into a new and glorious age marked by the revival of the great Ethiopian empire, taking advantage of Africa as a land of opportunity.xlii He declared: "One day all Negroes hope to look to Africa as the land of their vine and fig tree."xliii As a means of securing support for the objective of Africa, a region with a relatively heathen past, Garvey additionally emphasised the role of Africans in the Christian religion, with special reference to their mention in the Bible.xliv Garvey militantly called on the African peoples to be prepared to sacrifice themselves if need be to obtain the African homeland and allow for racial regeneration, "...so long as white men are going to rule and brutalize black men just so long must we continue to prepare for the greatest war in the history of the human race."xlv

As much as Garvey regarded Africa as important, however, his emphasis upon the doctrine of success overrode any interests in the "primitive" societies of Africa, and Garvey showed that he was impartial to European standards of civilisation and culture.xlvi Indeed, Garvey went so far as to teach that it was the role of the UNIA to "...assist in civilising the backward tribes of Africa" as a means of encouraging the development of the African race.xlvii To this end, Marcus Garvey placed a premium upon encouraging an education that emphasised literature and poetry, African history, and a study of the classics,xlviii even as he expressed a somewhat paradoxical opposition to black folk culture.xlix Undoubtedly, Garvey believed that African-Americans could expect no progress in a land which was dominated by whites, and for this reason Africa would have to be civilised for those who wished to improve their situation outside of the United States.l

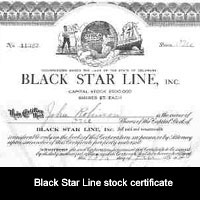

Having considered the principal elements which encompassed the ideology of Garveyism, and bearing in mind the militant and candid manner in which Garvey conveyed his ideas, it is not surprising that the UNIA experienced remarkable growth in 1919 and 1920, particularly as the propaganda of the widely circulated UNIA New York newspaper, "Negro World" reached a larger following,li and as Garvey was able to show physical proof that many of his plans and programmes had become reality. In particular, the ill-fated Black Star Shipping line silenced many of Garvey's critics at least initially, as he prepared in 1921 to send a delegation to Liberia;lii and the Negro Factories Corporation and chain of businesses set up by the UNIA encouraged African-American economic independence, and convinced many of the viability of separatist black communities.liii

Having considered the principal elements which encompassed the ideology of Garveyism, and bearing in mind the militant and candid manner in which Garvey conveyed his ideas, it is not surprising that the UNIA experienced remarkable growth in 1919 and 1920, particularly as the propaganda of the widely circulated UNIA New York newspaper, "Negro World" reached a larger following,li and as Garvey was able to show physical proof that many of his plans and programmes had become reality. In particular, the ill-fated Black Star Shipping line silenced many of Garvey's critics at least initially, as he prepared in 1921 to send a delegation to Liberia;lii and the Negro Factories Corporation and chain of businesses set up by the UNIA encouraged African-American economic independence, and convinced many of the viability of separatist black communities.liii

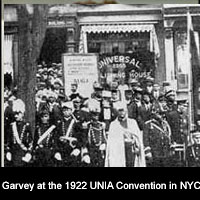

The UNIA Convention of August, 1920 marked the peak of the Garvey movement,liv and its grand parades, delegates from various countries and the pomp and ceremony of the occasion was very impressive, and instilled a sense of awe, confidence and hope in the directions which Marcus Garvey would take the UNIA in the future, especially in light of the promising Negro Declaration of Independence which emerged from the convention- a thorough document of some fifty-four articles which clearly and assertively protested many of the grievances of the UNIA (and indeed the African race as whole).lv In the years immediately after World War One Marcus Garvey had an audience that was receptive, and prepared to digest his ideas, and it is for this reason that one commentator in 1920 stated that it appeared that "The followers of Garvey believe that to be loyal to Garvey is to be loyal to their race."lvi Garvey's doctrine of success certainly captured the hearts and minds of thousands of people during this period.

With this combination of populist ideology and the physical impact of Garveyism, it is not surprising that Marcus Garvey evoked a powerful response not only from committed supporters, but from opponents as well. W.E.B Du Bois and the NAACP, for instance, engaged in a prolonged war of words with Garvey,lvii principally over his controversial stance on racial purity and encouragement of separatism, which he increasingly emphasised after the second UNIA convention of 1921.lviii Integrationist groups such as the NAACP feared that when Garvey preached "For a Negro man to marry someone who does not look like his mother or not a member of his race is to insult his mother, insult nature and insult God who made his father", that he would be understood to be the African-American spokesman for white America, representing a majority of black opinion.lix When Garvey forwarded the proposition that ‘mulattoes and brown-skinned people’ were to think of themselves as monstrosities to be bred out of existence, Du Bois, of mixed race himself, took particular offence.lx On other matters, Du Bois was opposed to Garvey's anti-miscegenation rhetoric,lxi and he was critical of Garvey's unrealistic dreams and dismissed UNIA pageantry as appearing like the "dress rehearsal of a new comic opera."lxii Above all, Du Bois viewed Garvey as an unstable demagogue.lxiii Several detractors of Garvey also could not comprehend how he, as the elected "Provisional President of Africa" would redeem and re-colonise the continent without the consent and co-operation of the "...black kings, chiefs and presidents who were born and elected to rule the natives of Africa."lxiv

Other groups that were significant in their response to Garvey were the agitated colonial governments of the several regions targeted by Garveyism,lxv and the United States government's Federal Bureau of Investigation and Department of Defense, whose inquiries into Marcus Garvey and the UNIA as potential subversive threats to the safety and domestic peace of America are well documented.lxviFinally, the increasingly radical wings of the African-American political movement, such as the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB) were responsive to Garveyism in publicly criticising the financial status of the Black Star Line in 1921.lxvii And, like African-American leader A. Philip Randolph and organisations such as the NAACP, the ABB were particularly critical of Garvey's highly controversial 1922 "compromise" with the Ku Klux Klan which asserted that Klan ideals of racial purity were no different to those of the UNIA, and no less unjustified.lxviii

Garvey's ideological foundations and the activities that the UNIA correspondingly embarked upon were well received until the decline of Garveyism amid his conviction for mail fraud in 1923.lxix In the preceding years, Garvey had successfully been able to harness the support and loyalty of a global black consciousness that demanded more immediate measures to be taken in overcoming the inequalities of white society. Garvey's emphasis upon the doctrines of success and race pride, merged with Africanism, religion, economic self-determination and the themes of civilisation and acculturation were expressed in such a way as many had never heard before, and Garvey's grandiose dreams encouraged the growth of the movement even further, when the material gains and products of the UNIA continued to epitomise Garvey's ideology and express his goals for the African race. Since Garvey's racial programme was so broad and attracted such a large popular following, it also inevitably came into contact with rival organisations, and conflicting theories on race relations. What is certainly apparent is that in the years after World War One, Marcus Garvey and the UNIA represented a timely and fresh expression of a Black Nationalism, and this encouraged a powerful response from the white and black communities of the world that were touched by the movement.

Garvey's ideological foundations and the activities that the UNIA correspondingly embarked upon were well received until the decline of Garveyism amid his conviction for mail fraud in 1923.lxix In the preceding years, Garvey had successfully been able to harness the support and loyalty of a global black consciousness that demanded more immediate measures to be taken in overcoming the inequalities of white society. Garvey's emphasis upon the doctrines of success and race pride, merged with Africanism, religion, economic self-determination and the themes of civilisation and acculturation were expressed in such a way as many had never heard before, and Garvey's grandiose dreams encouraged the growth of the movement even further, when the material gains and products of the UNIA continued to epitomise Garvey's ideology and express his goals for the African race. Since Garvey's racial programme was so broad and attracted such a large popular following, it also inevitably came into contact with rival organisations, and conflicting theories on race relations. What is certainly apparent is that in the years after World War One, Marcus Garvey and the UNIA represented a timely and fresh expression of a Black Nationalism, and this encouraged a powerful response from the white and black communities of the world that were touched by the movement.

END NOTES:

i Published in the Negro World, 6 June, 1925, see Robert. A Hill (ed.). Marcus Garvey- Life and Lessons. A Centennial Companion to the Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, University of California Press, 1987, p.6.

i Published in the Negro World, 6 June, 1925, see Robert. A Hill (ed.). Marcus Garvey- Life and Lessons. A Centennial Companion to the Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, University of California Press, 1987, p.6.

ii "From early youth I discovered that there was prejudice against me because of my colour, a prejudice that was extended to other members of my race. This annoyed me and helped to inspire me to create sentiment that would act favorably to the black man." Article from the Pittsburgh Courier, Ibid., p.35.

iii Garvey stated that after reading Booker T. Washington's book "Up From Slavery" he became aware of his "doom" of being destined to be a race leader. "The Negro's Greatest Enemy", published in Current History, September 1923, see Robert. A Hill (ed.). The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, Vol.1, University of California Press, 1984, p.5.

iv Speech by Marcus Garvey, New York, September 25, 1921, in Ibid., Vol.4, p.87.

v Garvey wrote to the House of Representatives of the United States in 1917, for instance that, "We beg to call your attention to the discrepancy which exists between the public profession of the government that we are lavishing our resources of men and money in this war in order to make the world safe for democracy.... Just as public performances of lynching-bees, Jim-crowism and disfranchisement in which our common country abounds. We should like to believe in our government's professions of Democracy, but find it hard to do so in the presence of the facts; and we judge that millions of other people outside of the country will find it just as hard." Quoted in Newspaper Report from the Brooklyn Advocate, see Ibid., Vol.1, p.222.

vi As epitomised in the spirit and symbolism of the (albeit short-lived) Black Star Shipping Line.

vii Quoted in Randall K. Burkett, Garveyism as a Religious Movement, The Scarecrow Press Inc., 1978, p.xv.

viii Deirdre Mullane (ed.). Crossing the Danger Water- Three Hundred Years of African-American Writing, Anchor Books, 1993, p.681.

ix Wilson Jeremiah Moses. Black Messiahs and Uncle Toms, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993, p.128.

x As an example, Chicago's Negro population rose from 44,103 to 109,594 during this period, an increase of some 150 per cent. E. David Cronon. Black Moses- The Story of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association, University of Wisconsin Press, 1955, p.23. See also pp.22-27.

xi Ibid., p.26.

xii As discussed in a speech delivered by Marcus Garvey on December 18, 1918, in Baltimore, Maryland. See The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.1, p.330.

xiii Cronon, op.cit., p.28.

xiv Judith Stein. The World of Marcus Garvey- Race and Class in Modern Society, Louisiana State University Press, 1986, p.40.

xv Cronon, op.cit., p.27.

xvi Garvey shared this grievance, petitioning the Congress of the United States in 1919 to vote against allowing the "gigantic robbery" of the constitution of the proposed League of Nations to be accepted. "Petition by Marcus Garvey", February 1919, The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol. 1, pp.366-370.

xvii The success of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in particular was important in convincing many African-Americans of the effectiveness of revolution as a means of immediate social change rather than the alternative of slow reform. Stein, op.cit., p.38. See also William H. Ferris' article in The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.2, pp.472-473.

xviii Garvey further recounted the lynching of an African-American in the uniform of the United States Army upon his return to America, just as President Wilson landed in France for the Versailles Peace Conference. Ibid., Vol.1, p.332.

xix Race rioting in East St. Louis in July, 1917 was especially controversial, where thirty-nine blacks and nine whites were killed. Note Garvey's speech on the riot, charging that white participants to the conflict "feasted on the blood on the Negro..." in Ibid., pp.212-222.

xx Lerone Bennett Jr. The Shaping of Black America, Penguin Books, 1993, p.269. Garvey himself stated in 1923 that "The war helped a great deal in arousing the consciousness of the coloured people to the reasonableness of our programme." The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.1, p.6.

xxi "The coloured race is greatly in need of a Moses- one that is not hand-picked or controlled by the blandishments of official environment- a man of the people and designated by the people." Garvey, November 1918, Ibid., p.xxxviii.

xxii Tony Martin. Race First, The Ideological and Organisational Struggles of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association, Greenwood Press, 1976, p.9.

xxiii Further, he encouraged Africans to recognise the beauty of their own race, and to resist accepting white notions of what was beautiful or attractive: "Black Queen of beauty, thou hast given colour to the world". From the poem "Black Woman", The Poetic Meditations of Marcus Garvey, 1927, quoted in Martin, op.cit., p.23.

xxiv Garvey, The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.2, p.253.

xxv Stated in March 1938, quoted in Hill, Marcus Garvey- Life and Lessons, op.cit., p.xxv.

xxvi "...God almighty never could have made such a terrible mistake- to make four hundred million people black." The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.3, p.26.

xxvii Garvey stated in July 1935 that "...wealth is strength, wealth is power, wealth is influence, wealth is justice, is liberty, is real human rights." Ibid., p.xxvii.

xxviiiIbid., Vol. 2, p.458.

xxix Garvey's "New Thought" ideology emphasised mind mastery, self-help, and the determination to improve the position of one's race. Hill, Marcus Garvey- Life and Lessons, op.cit., p.xxviii.

xxx Ibid., pp.183-351.

xxxi Ibid., "Economy", pp.253-259, "Commercial and Industrial Transactions", pp.300-311.

xxxii For example the Jews and the Italians. Ibid., p.302.

xxxiiiIbid., "God", pp.221-224, and "Christ", pp.225-233.

xxxiv A right which he believed was greater than that of white people since Simon of Cyrene -a black man- was the only person who ever bore the cross for Jesus Christ. Ibid., p.231.

xxxv The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.3, p.161.

xxxvi Ibid., p.162. Garvey's "Universal Negro Creed" of 1919 ended with the line: "I believe in a colourless God." The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.2, p.163.

xxxvii Burkett, op.cit., p.7, see also Moses, op.cit., p.139.

xxxviii Editorial Letter by Garvey, June 10, 1919. The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.1, pp.415-416.

xxxix Moses, op.cit., pp.15, 124. At the 1926 UNIA convention, for example, amidst the seeming religious fervor of several of Garvey's followers, the secretary-general referred to him as the "star of hope, born 38 years ago." The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.1, p.xlvi.

xl Burkett, op.cit., p.xx.

xli Discussed in Lesson 3- "Aims and Objects of the UNIA", see Hill, Marcus Garvey- Life and Lessons, op.cit., p.206-214. See also Garvey's criticism of white mainstream world history at The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.3, p.215, and the historical emphases of the Universal Negro Catechism, pp.307-312.

xdlii Ibid., Vol.1, p.lxxxvii.

xliii Hill, Marcus Garvey- Life and Lessons, op.cit., p.207.

xliv Note that the "Universal Negro Catechism" of 1921 prioritizes the greatness of African religious leaders, and interprets expressions of race pride and the need for African self-rule from the Bible, even as many aspects and 'heroes' of the African heritage were totally independent from any Christian past. The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.3, pp.302-307. See also Ibid., Vol.1, p.xliv. As one author pointed out, the political parallels between Garveyism and Zionism are remarkable. Hill, Marcus Garvey- Life and Lessons, op.cit., p.liii.

xlv The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.2, p.187. Note also Garvey's speech that "Africa must be restored", p.117. In 1919 Garvey asserted that in Africa, by sheer numbers, "...where there are over four hundred million Negroes, we can make the white man eat his salt. Ibid., Vol.1, p.377.

xlvi Moses, op.cit., p.132.

xlvii Hill, Marcus Garvey- Life and Lessons, op.cit., p.207.

xlviii Garvey's poem "The Tragedy of White Injustice" opens with the assertion that "Lying and stealing is the whiteman's game." Ibid., pp.xxx-xliii.

xlixThe Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.1, p.li.

l Garvey, "Philisophy and Opinions", in Cronon, op.cit., p.187.

li The circulation of which varied between 60,000 to 200,000 in its most prosperous years. Ibid., p.45.

lii Garvey planned to repatriate between 50,000 and 1,000,000 African-Americans in 1921. The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.3, p.114.

liii Garvey's range of business ventures are presented in a 1921 F.B.I report at Ibid., p.399. See also Cronon, op.cit., p.60.

liv See Deirdre Mullane, op.cit., p.469.

lv Article I stated, for example: "That nowhere in the world, with few exceptions, are black men accorded the same equal treatment as white men...", and Article 13: "We believe in the freedom of Africa for the Negro people of the world." The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.2, pp.571-578.

lvi Anselmo R. Jackson, in The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.2, p.276.

lvii Note Garvey's scathing criticism of Du Bois in an April, 1919 address, in Ibid., p.394-399.

lviii Martin, op.cit., p.13. Garvey was particularly opposed to the NAACP's reliance upon varying degrees of white-funding, and that some whites were even employed in the organisation. Editorial Letter by Garvey, December 7, 1921, The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.4, p.249.

lix Lesson 2- "Leadership", in Hill, Marcus Garvey- Life and Lessons, op.cit., p.203.

lx Moses, op.cit., p.140. "Garvey has publicly stated that before his movement can hope to be a final and assured success all the mulattoes in the world must be killed..." Interview with Chandler Owen and A. Philip Randolph by Charles Mowbray White, August 1920, Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.2, p.611.

lxi Ibid., p.130.

lxii Hill, Marcus Garvey- Life and Lessons, op.cit., p.xxiii.

lxiii Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol. 1, p.lv.

lxiv Madarikan Deniyi to the Richmond Planet, January 29, 1921, Ibid., Vol. 3, p.145.

lxv As an example, "The Negro World" was banned from circulation in British Honduras in February, 1919, on the grounds of inciting racial hatred. Ibid., Vol.1, pp.371-372.

lxvi For instance note the several F.B.I reports of Garvey's day-to-day activities, as reported by various Special Agents. Ibid., Vol.4, pp.521-527. Authorities were particularly alarmed in September of 1919 when Garvey made an appeal during a speech to have a white man lynched for every Negro who was lynched. Ibid., Vol.1, p.19.

lxvii Cyril V. Briggs of the ABB was especially critical of Garvey and the UNIA in 1921. See Ibid., Vol.4, pp.62-66.

lxviii Garvey's justification of the Ku Klux Klan: "You cannot blame any group of men... for standing up for their interests or for organising in their interest", in Ibid., Vol.4, pp.707-715. For a further analysis note the discussion in Stein, op.cit., pp.153-170.

lxix See Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Papers, op.cit., Vol.4, p.302.