- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

The Cud Essay: |

Policing in Australia is influenced by a number of factors, including gender, class, age, and politics.

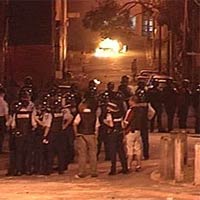

Race is especially significant in this respect, given Australia's native Aboriginal population and broad multicultural society, and received particular focus amid Sydney’s race-motivated riots of 2005. The existence of a 'police culture' both in Australia and abroad that affects the way in which police make determinations of crime and criminality as part of the criminal justice system has been long recognized.1 Generally speaking, this police culture is defined as a pattern of behavior and 'unwritten rules' that develop out of the nature and condition of police work. Or, as Janet Chan has defined it, "... police culture results from an interaction between the 'field' of policing and the various dimensions of police organisational knowledge."2 Within this culture, it is argued that police come to identify and, effectively, demonize a certain type of criminal or group of troublemakers that are perceived to be threatening not only society as a whole, but also the authority and values for which the police themselves stand.3 This in turn affects the attitudes of native and ethnic Australians towards the police force. Clearly, when race becomes a central concern in this police culture, it threatens the fair operation of the criminal justice system and the success of initiatives such as community policing.4

Australia is home to more than 100 ethnic groups, speaking 80 different immigrant and over 150 Aboriginal languages.5 Although it would be misguided to make the generalisation that all police are racist, it would also certainly be incorrect to assert that the police culture as a whole does not contain some elements of racism, and that this does not therefore affect methods and approaches to policing. One particular problem that is often cited in Australia, especially in relation to the Aboriginal population, is that of 'over-policing'.6

Australia is home to more than 100 ethnic groups, speaking 80 different immigrant and over 150 Aboriginal languages.5 Although it would be misguided to make the generalisation that all police are racist, it would also certainly be incorrect to assert that the police culture as a whole does not contain some elements of racism, and that this does not therefore affect methods and approaches to policing. One particular problem that is often cited in Australia, especially in relation to the Aboriginal population, is that of 'over-policing'.6

Historically, relations between the police and Australia's indigenous people have been strained, and the native title and pastoral lease controversies of recent years aroused further tension.7 The Police Service would generally defend over-policing in areas such as rural N.S.W where there is a disproportionate number of police to the local Aboriginal populations by stating that communities simply get the level of policing that 'professional' judgment and police discretion deems appropriate.8It seems unlikely, however, that these discretionary powers have always been used in the best interests of community policing, especially when evidence exists to show that over-policing can actually encourage hostility towards the police more than had existed before.9 This has particularly proven to be the case in overseas examples such as North America, where:

"... hostility is concentrated among those low-income or unemployed black males who are the special targets of heavy policing.... the police stop and question young, low-income minority males more frequently than any other group."10

When police antipathy toward Aborigines is combined with similar accounts of aversion towards other ethnic minorities in Australia (a problem rooted in our history from the era of the White Australia Policy to the 'immigration debate' of the 1980's),11 over-policing contributes to the higher statistical composition of ethnic minorities which exist in our prisons compared to those prisoners of Anglo-Australian origin.12 Improved relations between the police and minorities might forseeably reduce the crime rate for these groups.

When police antipathy toward Aborigines is combined with similar accounts of aversion towards other ethnic minorities in Australia (a problem rooted in our history from the era of the White Australia Policy to the 'immigration debate' of the 1980's),11 over-policing contributes to the higher statistical composition of ethnic minorities which exist in our prisons compared to those prisoners of Anglo-Australian origin.12 Improved relations between the police and minorities might forseeably reduce the crime rate for these groups.

One aspect of the poor relationships that exist between many police and ethnic or minority groups at the community level, and which is perhaps quite obvious, is the circular effect of over-policing and racism in the force. An observational study from the United States that is still relevant to the Australian perspective showed that a high incidence of 'stop and search' encounters and of arrests of young blacks flowed, in part, from the greater rate at which they showed disrespect for the police, and "... the greater likelihood of being involved in incidents where complainants (usually black) demanded arrest." Such hostility, however, often flows from the initial behavior of the police themselves, either historically (as discussed, briefly, above), or from the conduct of police in the actual cases involving minority individuals.13

Two very real hurdles that must be overcome if initiatives like community policing are to work are the language barrier and the cultural barrier that restrict communication and co-operation between the police and minority groups. On average, officers encounter a problem with language about 52 times a year,14 and the Ethnic Affairs Commission foreign language communication service that is available for police is very much under utilised. Very few individuals within the N.S.W Police Service operate under the Community Language Allowance Scheme, a programme that offers police employees an allowance if they use their community language skills in their public and other police duties.15 If language is a constant source of difficulty for police officers in the course of their duties, then it may well arguably contribute to racist or other similarly negative attitudes.

Culturally, there is a very real need to address the conflict that occur when police encounter a culture that they do not understand or, conversely, when minority groups are unfamiliar with police procedure and operations in Australia. Immigrants that originate from countries where experiences with police are in stark contrast to our own may feel mistrust or fear of the police force, as may be the case for many Aborigines.16 Further, there may be an unwillingness to react to mistreatment or discrimination from police because there is a general lack of knowledge of the various avenues of redress.17 A 1992 survey found that 43 per cent of people of non-English speaking background and only 30 per cent of Aborigines had ever heard of the Commonwealth Ombudsman, let alone being able to comprehend the actual process involved in lodging a complaint.18 Though we cannot expect police to be familiar with every culture, or for minority groups to thoroughly understand the Australian criminal justice system, problems in policing may be avoided via the appropriate education.

Culturally, there is a very real need to address the conflict that occur when police encounter a culture that they do not understand or, conversely, when minority groups are unfamiliar with police procedure and operations in Australia. Immigrants that originate from countries where experiences with police are in stark contrast to our own may feel mistrust or fear of the police force, as may be the case for many Aborigines.16 Further, there may be an unwillingness to react to mistreatment or discrimination from police because there is a general lack of knowledge of the various avenues of redress.17 A 1992 survey found that 43 per cent of people of non-English speaking background and only 30 per cent of Aborigines had ever heard of the Commonwealth Ombudsman, let alone being able to comprehend the actual process involved in lodging a complaint.18 Though we cannot expect police to be familiar with every culture, or for minority groups to thoroughly understand the Australian criminal justice system, problems in policing may be avoided via the appropriate education.

Reform, then, is the most important step forward which must be made in order to remedy the current conceptions of crime and criminality maintained by many police. Or, as Clifford Shearing elucidated in his discussion of the police culture in South Africa, the strategy to be pursued is:

"... finding expression both in the rewriting of internal regulations and legislation and the development of a massive retraining programme to make these new directions known and thereby to redirect the script of the occupational culture."19

The 1992 ABC documentary "Cop It Sweet", presented a shocking insight into policing in Redfern, and had the effect of encouraging a shift towards further police reform and public accountability.20 However, though various recruitment and training measures have been adopted in recent years, they have not all had the widespread effect upon the police culture that they necessarily intended.  The removal of height restrictions for entry into the Police Service, and the setting of certain recruitment objectives have allowed more minority groups access into a police career, however until the appropriate affirmative action legislation is enacted in N.S.W, the Police Service will still primarily be composed of individuals of Anglo-Australian origin.21

The removal of height restrictions for entry into the Police Service, and the setting of certain recruitment objectives have allowed more minority groups access into a police career, however until the appropriate affirmative action legislation is enacted in N.S.W, the Police Service will still primarily be composed of individuals of Anglo-Australian origin.21

Similarly, initiatives that have aimed to address ethnic and native concerns, like the establishment of Community Consultative Committees in 1987, and a National Police Ethnic Advisory Bureau in 1991 will be of little use if communication is still fettered by a lack of education, cultural familiarity, or the appropriate legislative and other machinery needed to allow more successful 'grass-roots' interaction.22

Although problems with race have created difficulties in community policing and other similar initiatives, both in Australia and abroad (in areas like South Africa, North America, and England), it is important to recognise that race is obviously not the sole contributing factor for police in determining crime and criminality, and it would be wholly wrong and irresponsible to pin the blame for last year’s Sydney riots upon a failure by the police to grasp the racial issues at play within the community.23 Rather, elements such as age, gender and class are all intertwined and cannot generally stand distinct, as they intersect to form a broader police culture.  That aside, when a lack of general understanding, ignorance and hostility does prevail in the relationship between the police and minority groups we cannot expect the ethnic make-up of the Australian Police Service to be especially high, and this is an important arm of the police which must be developed as a means of breaking down the systemic racism that is an inherent part of some aspects of the police culture, and might otherwise make the force more 'approachable' for the community.24 If policing in a multicultural Australia is to operate both responsively and responsibly, then there is a very real need for rule tightening and reform of the informal police culture.25

That aside, when a lack of general understanding, ignorance and hostility does prevail in the relationship between the police and minority groups we cannot expect the ethnic make-up of the Australian Police Service to be especially high, and this is an important arm of the police which must be developed as a means of breaking down the systemic racism that is an inherent part of some aspects of the police culture, and might otherwise make the force more 'approachable' for the community.24 If policing in a multicultural Australia is to operate both responsively and responsibly, then there is a very real need for rule tightening and reform of the informal police culture.25

ENDNOTES:

1 For analysis of the police culture with respect to race in South Africa see Clifford Shearing, "Transforming the Culture of Policing: Thoughts from South Africa, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, Special Supplementary Issue, 1995, 54-61, and for England and North America see M. Brogden, T. Jefferson and S. Walkate, Introducing Policework, Unwin Hyman, 1988, especially pp.124-141.

2See Janet Chan, "Changing Police Culture", British Journal of Criminology, 36(1), 1996, pp.109-134 [Excerpts].

3 Shearing, op.cit., p.55.

4 See David B. Moore, "Police Responses to Community Policing", in S. McKillop and J. Vernon (eds.). The Police and the Community in the 1990's, Australian Institute of Criminology, 1991, pp.219-229.

5 S. Castles, B. Cope, M. Kalantzis and M. Morissey, Mistaken Identity, Pluto Books, 1988.

6 See Chan, op.cit.

7Ibid., p.116.

8 Brogden, Jefferson and Walkate, op.cit., p.124.

9 See Chris Cunneen, in "Problems in the Implementation of Community Policing Strategies", McKillop and Vernon, op.cit., p.162. Inquiries into the over-policing of Aboriginal and Islander People have found on several occasions "overwhelming evidence" of police violence. Chan, op.cit., p.118.

10 Examples such as this, which in its most extreme manifestation was realised in the reaction of the Los Angeles riots of 1992 should serve as lessons for Australia on ways in which to improve our Police Service. See Brogden, Jefferson and Walkate, op.cit., pp.128-129.

11 Chan, op.cit., p.117.

12 Per 100,000, the number of male prisoners whose country of birth was Oceania and New Zealand, the Middle East and Lebanon, far outweighed the composition of prisoners born in Australia. National Prison Census, 30 June 1982-85, Australian Institute of Criminology, 1981 Population and Housing Census, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1981.

13 The Black-Reiss observational study. In Brogden, Jefferson and Walkate, op.cit., p.136.

14From a 1991 survey, cited in J. Chan, Changing Police Culture, Policing in a Multicultural Society, Cambridge University Press, 1997.

15 See Ethnic Affairs Commission, Police and Ethnic Communities, November, 1994.

16 J. Donoghue, "The Effect of Policing in Post-War Immigration", Australian Police College Journal, 1982, pp.5-25.

17 Brogden, Jefferson and Walkate, op.cit., p.134.

18 Janet Chan, "Changing Police Culture", op.cit., p.119.

19 Shearing, op.cit., p.56.

20 Chan, "Changing Police Culture", op.cit., p.109.

21Ibid., p.123.

22As was the case in the appointment of Ethnic and Aboriginal Community Liaison Officers as temporary staff of the N.S.W Police Force in 1991. Chan, Changing Police Culture, Policing in a Multicultural Society, op.cit., p.140.

23 Brogden, Jefferson and Walkate, op.cit., p.124, also 128.

24 So long as these individuals do not then become a part of the status quo and take on the cultural perspectives of the negative police culture. Ibid., p.126.

25 Chan, "Changing Police Culture", op.cit., p.130.