- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

The Life Of A Poet |

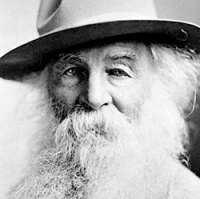

They tell you to write what you know; well, this is what I know. Since the age of seventeen I have been a poet. I have suffered through periods of writer’s block that have lasted several weeks to several months. There have been many instances when time has been so constricted that I cannot find an hour to pen verses even if I wanted to; at other times there have been dry spells where there is no inspiration, nothing to rattle this bird cage of a body in which I dwell, a spirit broken, saturated, and knocking against flesh that will not heal, and will not bend to the restless soul. Writer’s block is torture, and infinitely more daunting in the depression with which it punishes the poet. There is a great sorrow and despair that cannot be breached when the poet lays down his pen, puts away his journal, and cannot find solace even in a literary masterpiece, a work of art, or a song. The terror comes from the abyss the poet faces that opens up to him, echoing in sounds that only get louder as the days go by that say, “Will you ever write again?” It is this thought that terrifies the poet. It does so only because the poet is born, and not made. His style, his choice of themes may be cultivated over time, through practice, and experience, but his human identity is given him at birth, though he may not discover it for years, and then must invent his poetic persona in time. But the person and the nature of the poet are two different things: I may feign hysteria and publicly embody an androgynous and even elitist figure, but this is merely a mask to hide the inborn temperament of the poet, of the artist in general.

Writer’s block is torture, and infinitely more daunting in the depression with which it punishes the poet. There is a great sorrow and despair that cannot be breached when the poet lays down his pen, puts away his journal, and cannot find solace even in a literary masterpiece, a work of art, or a song. The terror comes from the abyss the poet faces that opens up to him, echoing in sounds that only get louder as the days go by that say, “Will you ever write again?” It is this thought that terrifies the poet. It does so only because the poet is born, and not made. His style, his choice of themes may be cultivated over time, through practice, and experience, but his human identity is given him at birth, though he may not discover it for years, and then must invent his poetic persona in time. But the person and the nature of the poet are two different things: I may feign hysteria and publicly embody an androgynous and even elitist figure, but this is merely a mask to hide the inborn temperament of the poet, of the artist in general.

When you take language away from the poet, when you silence his tongue you violate his inner sanctum. We all may love what we do and become professionally, but the poet had no choice in this. I cannot ever give a moment’s thought to the belief that artists and poets can be schooled and educated in their skills; talent can be refined and channeled but not created. A poet fears putting down his pen because if he never picks it up again, his whole identity, his very divinity of soul, is vanquished and vanishes beneath the material nature of human life. The very meaning of his existence becomes void, and without this meaning, he is truly lost.

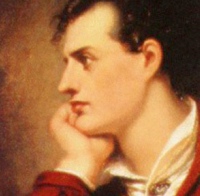

A poet by his very nature is a dreamer, a Romantic, an idealist. He has faith; he believes, foolishly, against his will and his better judgment, he believes. The aim of all poetry is beauty, and the pleasure and subsequently the self-realization or enlightenment offered by that beauty. The purpose of poetry is to transfigure and strive for transcendence; it may intentionally lie or alter reality but it does so to suit its purposes, and those objectives are fundamentally to unite the human race in a common and fruitful perception of itself as the Human Form Divine, as Blake conceives the figure of Christ. Woe to any who can believe the poetry they read as partaking in the factual minutiae of everyday life and reality. The poet takes the barest of these facts and fabricates on his loom of language a world higher and more universal than that which any single person can see under the burden of our material existence.

Any ordinary reader of poetry does not and truly cannot comprehend the inner life of the poet. True poets, like true artists, hide their agony beneath the surface of their language and the materials they use to create a work of art. All truly great art is about the surface; about the words you read and the painting or sculpture you see before you. The art of art is in the act or pose of deflection. All art and poetry is highly and fundamentally autobiographical because it materializes and literalizes how the artist and poet envision the world or how they wish the world really were. No one can really understand the emotional life of a poet; we are the most sensitive, damaged, and exiled of people. So often I use the figure of Cassandra, the blind prophet of Greek myth in the age of the Trojan War, in my poetry, because she, like Tiresias, has been given the curse of literal blindness and the supposed gift of the second sight of prophecy. But, the gift of knowing, of being able to see beyond what others normally know and can perceive is even more of a curse, because like her, poets are barely believed or welcomed into society. Poetry is, in its way, the gift and curse of prophecy: to know, to see, to feel more deeply and intimately, with a greater intensity and severity than any other human being. It is an unfortunate truth that to serve humanity poets must be outside the fold, by our very nature we do not and cannot conform to the constraints and simplistic, dull-minded brainwashing of society on the human race. To punish us for this, society does not publish our work, and if it does, it gives us the sparsest remuneration, if any at all, for our pangs and suffering as an exile that is doubly God-given and socially sanctioned.

All art and poetry is highly and fundamentally autobiographical because it materializes and literalizes how the artist and poet envision the world or how they wish the world really were. No one can really understand the emotional life of a poet; we are the most sensitive, damaged, and exiled of people. So often I use the figure of Cassandra, the blind prophet of Greek myth in the age of the Trojan War, in my poetry, because she, like Tiresias, has been given the curse of literal blindness and the supposed gift of the second sight of prophecy. But, the gift of knowing, of being able to see beyond what others normally know and can perceive is even more of a curse, because like her, poets are barely believed or welcomed into society. Poetry is, in its way, the gift and curse of prophecy: to know, to see, to feel more deeply and intimately, with a greater intensity and severity than any other human being. It is an unfortunate truth that to serve humanity poets must be outside the fold, by our very nature we do not and cannot conform to the constraints and simplistic, dull-minded brainwashing of society on the human race. To punish us for this, society does not publish our work, and if it does, it gives us the sparsest remuneration, if any at all, for our pangs and suffering as an exile that is doubly God-given and socially sanctioned.

A poet’s life is not pretty, normal, or fascinating in the least. A poet endures, he suffers, and experiences all the tragedies and beauties of life; the only two differences are that he takes languages and creates images, scenes, and poetry from his experiences and his deep reflection on these experiences, while the other difference is that he is more sensitive to the Reality that is the foundation of all life. He sees past the materiality in nature and human life in society and culture that clouds man’s perceptions of the more important things and tries to create art from what he perceives. Thus, his emotional life is and must be more chaotic and subject to the whims of Nature and the cosmos; the harmonies and dissension that exist throughout all Creation is concentrated within the various planes and recesses of his mind and body, laying siege to his heart and battering him into a contorted, weak, even at times sickly and empty figure because only in a storm of mental and emotional turmoil can art and poetry be created. Love, the greatest of all the poet’s themes, can only be written about when in the state of being disturbed by the lover or beloved. Love cannot be written of in a state of contentment or when reason is ascendant in the poet’s mind, rather Love can only be sung of when it has broken the heart into a million pieces and guillotined the figurehead of Reason. Poets are “mad” because they are swollen and infused with the reality of Love as the most sweeping force in the entire universe. Love is their daemon; poets are the reluctant sacrifice on the altar of Love, they must be found in tears at the feet of their lover/beloved so that humankind can be redeemed.

He sees past the materiality in nature and human life in society and culture that clouds man’s perceptions of the more important things and tries to create art from what he perceives. Thus, his emotional life is and must be more chaotic and subject to the whims of Nature and the cosmos; the harmonies and dissension that exist throughout all Creation is concentrated within the various planes and recesses of his mind and body, laying siege to his heart and battering him into a contorted, weak, even at times sickly and empty figure because only in a storm of mental and emotional turmoil can art and poetry be created. Love, the greatest of all the poet’s themes, can only be written about when in the state of being disturbed by the lover or beloved. Love cannot be written of in a state of contentment or when reason is ascendant in the poet’s mind, rather Love can only be sung of when it has broken the heart into a million pieces and guillotined the figurehead of Reason. Poets are “mad” because they are swollen and infused with the reality of Love as the most sweeping force in the entire universe. Love is their daemon; poets are the reluctant sacrifice on the altar of Love, they must be found in tears at the feet of their lover/beloved so that humankind can be redeemed.

All art, like religion, must have its sacrificial figures so that humanity can be shown the thorny, narrow, but nevertheless liberating path toward transcendence.