- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

January 2012 - Women Writers of the Greek Diaspora In Australia |

Penelope sat at home for many years weaving her winding sheet and keeping suitors at bay, while her husband Odysseus fought a ten-year war in Troy and followed this with a life of adventure on the high seas.

But Australia’s Greek women, whether first generation immigrants or their daughters and granddaughters, are no Penelopes. Especially in the case of the first generation Greek immigrant women, the life of waiting in the homeland was not for them. Instead they braved the unknown and came to this foreign land of the South ready to build a new life and a new future. And most of them, each in her own particular way and through her own determination, perseverance and courage has risen above the confines of a traditionally home-oriented life and, while still fulfilling all the family responsibilities, have at the same time made a valuable contribution to diverse aspects of Australian life, culture and the arts – one of them being literary writing – therefore weaving their own rich patterned cloth of life.

Instead they braved the unknown and came to this foreign land of the South ready to build a new life and a new future. And most of them, each in her own particular way and through her own determination, perseverance and courage has risen above the confines of a traditionally home-oriented life and, while still fulfilling all the family responsibilities, have at the same time made a valuable contribution to diverse aspects of Australian life, culture and the arts – one of them being literary writing – therefore weaving their own rich patterned cloth of life.

In reality the subject of woman and literature has a universal implication and is basically twofold: woman as she is portrayed in literature and woman as creator of literature and contributor to literary culture. However, the subject under examination here focuses on the second dimension and exclusively on Greek women writers in Australia.

First of all, it must be pointed out that the recognition of the Greek women writers in Australia (as well as in the other countries of the Greek diaspora) and the degree of impact of their work, beyond their personal talent, has been influenced, especially in the past, by the demographic, social and cultural factors which have determined the role and position of women, and therefore of women writers, within both the Greek community and the wider Australian society in which they live.

The decisive turning point which altered the course of the Greek literary presence in Australia was one which changed essentially the entire history of Greek immigration to this country and resulted in massive waves of emigration from all over Greece. That was the bilateral agreement signed in August 1952 by Australia and Greece by which the Australian Government would provide assisted passage to Greeks willing to emigrate (Kanarakis, 19912, p. 33). Of course the reasons behind this agreement for Australia were socio-economic (the need for more manpower for reconstruction and development after World War II) and also politico-military (defence), while for Greece they were the destructive results of World War II and the ensuing Civil War.

It is indicative that while in 1939 only 996 Greeks emigrated from Greece and in the period 1940-1946 just 467, in the year July 1952-June 1953 the figure increased to 1,979, in 1953-1954 to 5,361, in 1954-1955 to 12,885, in 1964-1965 to 17,896, with an overall intake of 229,955 in 1952-1983 (Department of Immigration, 1968, p. 32; Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, 1983, p. 35; Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1984, p. 12), reaching the number of 365,200 persons self-reported of Greek origin in the Australian census of 2006.

Regarding the immigration of Greek women, their demographic profile before and after the mid-1950s illustrates two opposite pictures in comparison with that of men. Before the mid-1950s the Greek women residents in Australia were in the minority compared with Greek men, while afterwards the gap started closing more and more. According to Australian statistics, in 1911 (the beginning of the decade in which we have the first flickerings of Greek literature in the Antipodes) the Greek-born female residents in Australia were only 106 in comparison to 1,714 Greek-born males. In 1921 the Greek-born females were only 507, whereas the Greek-born males were 3,147; in 1933 these numbers, although growing, were 1,788 females born in Greece to 6,541 Greek-born males; in 1947 3,176 females to 9,115 males and in 1954, 9,068 females to 16,794 males (Tsounis, 1971, pp. 579-580 Table III). The point evident here is that if from these small numbers of men only a few writers and oral poets emerged, in comparison how many fewer possibilities there were for writers to arise from the much smaller number of women.

Another factor which casts light on the small number of Greek immigrant women writers of those years, as well as on their somewhat later appearance in time, is the socio-cultural context, always a significant influence, particularly in that period.

Two aspects of Greek community life of social and psychological significance, which frequently created the suitable atmosphere and inspiration for literary expression in the form of oral rhyming verses spontaneously improvised under the stimulus of the moment were the coffee-house and public social activities, including family celebrations (feast days, baptisms, weddings, etc.). But there once again Greek women were disadvantaged because in the first instance it was not considered acceptable for them to frequent coffee-houses, a social institution only for men, and in the second, it was generally not deemed “proper” for women to recite publicly a poem they improvised under the influence of the atmosphere. The only opportunity for such a literary occasion was during social activities (showing the bridal trousseau, funeral gatherings, etc.) which were organised exclusively for and by women. This socio-cultural situation was due, on the one hand, to the role assigned then to Greek women reflecting the mores and customs of the male-dominant society of their homeland which were supposed to dignify a woman (giving her control over domestic affairs and children), and on the other hand, to most of those immigrant women’s low educational and socio-economic level.

According to the present results of my ongoing research on this subject, the earliest published women’s literary works I have located go back to the mid-1920s at a time when the number of Greek-born resident women were just over 500, while their more substantial quantitative increase to over 1,500 would be recorded a decade later (see also Tsounis, 1971, p. 579 Table III).

The picture of the Greek women’s literary presence during the 1920s until the bilateral agreement between Australia and Greece in August 1952, reveals published works of two genres, poetry and prose pieces. Poetry appears more frequently and by more women, but I have found no evidence or information regarding oral creations in either poetic or prose style. This does not mean that verses and tales were not improvised, particularly in the family environment, but if they were, they have been lost with the passage of time as these early voices of the past which constitute part of the oral history of Australian Hellenism were not recorded or collected when they were still present in the memories of the older Greeks of the communities.1

Another characteristic of the women’s published works, according to my findings, is that prose pieces appeared much earlier (1926 and 1927) than poems (1930s) in the Greek press of the time, the opposite trend noticed for men. The prose pieces were short stories, tales for children and a few feature articles while the poems were lyrical in style, with a few satirical ones towards the end of this period, composed in the traditional rhyming line. Historically, the women’s published poems spanned the decade of the 1930s and, with a gap in the 1940s, they reappeared invigorated in 1950, 1951 and 1952. In contrast, their prose pieces appeared more frequently from 1951 and continued successfully to the extent of prize winning as happened with the short story “The Match-making” by Katy Moulin (pen name) of Nambour, Queensland, which was awarded the first short story prize of the literary competition of the well known Melbourne magazine Oikoyenia (The Family) announced in its 19th issue of 31 August 1952. It is noteworthy that in the early years many women used to publish their works under pen names, such as Rhodiaki Avra (Rhodian Breeze), Amalias (female name), Horiatopoula (Rural Girl), etc., while others, as a popular romantic pastime, would write poems and prose pieces as a means of personal and social communication, often kept in an album or a drawer of scattered unpublished pages.

Another area of literary writing in which women writers have played a vital role and which is frequently overlooked, despite its pedagogical value, is children’s literature, in both poetic and prose forms. This genre started developing more systematically towards the end of the first period, with one of the early exponents being Pipina Tsimikali whose column “The Children’s Tale” appeared in Oikoyenia (No. 3, 15 April 1951 and onwards). It was not until the 1980s, however, that children’s literature by women writers would make its published appearance in English.

The contribution of the Greek community press of those early years for the promotion of the Greeks’ literary expression in general proved invaluable. Poems, short stories, tales for children and other forms of prose writing found a public medium in a variety of newspapers and magazines, such as the newspapers Panellinios Kiryx (Panhellenic Herald) of Sydney, Pharos (The Beacon) of Adelaide, Afstralo-Ellin/The Australian Greek of Melbourne and Angelioforos tis Kouinslandis/The Queensland Messenger and Ellino-Afstraliana Nea/Hellenic Australian News of Brisbane, as well as the magazines Oikoyenia and Ellino-Afstraliani Epitheorisi/Greek-Australian Review of Melbourne.

The themes of the Greek women’s literary writings of that early period were the usual ones of immigrant life, that is, xenitia, nostalgia for the homeland and the persons left behind, conflict between generations, the Australian social environment, etc. The interesting point is that the themes in these writings are portrayed in a more negative way than in many of the men’s works, and this because the women, deprived of many of the social outlets which men had, felt even more deeply the isolation from family and friends in Greece, as well as the familiar social support networks of the native land.

In general, these poems and short prose works have socio-cultural and historical significance, some indeed of literary value as well, but more significantly they present the personal reflections of the people who lived through the early half of the twentieth century experiences of migration to Australia, adjusting themselves to a new life in a different and often challenging circumstances, and who felt the need to express themselves by putting their thoughts and emotions into words. The literary works of those early times, considered by some as minor, in reality are of importance because first, they provide a window to those early years of Australian Hellenism; second, they indicate the vigorous maintenance of the Greek national values and ideals; and third, they often reveal more about the cultural and intellectual life of a period than that which the major works are considered to do.

After 1952, the quantitative increase of women in the Greek community, numerically and proportionately (in 1947 Greek women constituted 25.8% of the Greek population in Australia while by 1996 they had reached 48.9%), resulted in a noticeable rise in the number of Greek women writers, as well as a corresponding change for the better in the literary spectrum of Greek women in Australia, with a parallel expansion of the literary genres they served. Gradually we see an opening first towards prose (short stories, travelogues, literary feature articles, novellas and novels) and later towards playwriting (one-act and full length plays). It must be pointed out that among the playwrights there are also women writers who serve the logos of the theatre only as a literary genre, while others’ plays not only have been published in book form but have been staged, as well.

A new dimension in women’s writing which flourished in the post-1952 years has been the gnomic logos in both poetry and prose forms. The first exponent of this genre has been Dina Amanatides whose first such gnomic prose work “Scattered Thoughts” appeared in the first issue of the Melbourne periodical Antipodes as early as 1974.

From the thematic point of view, although the old themes relating to immigrant life in the foreign land continued to appear, the spectrum broadened significantly, even to existential content under the influence of European literary trends. This abundance of women’s writing with an expanded thematic spectrum of international dimensions can also be viewed as a feminist feat which is some cases even challenged the established order of Greek immigrant society. The post-1950 model of the Greek woman writer (poet, prose writer and playwright), as well as the woman as literary character projected in her writings, gradually became quite removed from that of pre-World War II times and is not the voice of unconditional surrender to an unchallenged patriarchal system, but an independent, developed voice no longer restrained from free thinking and choice.

As well, all the multi-dimensional expansion in literary genres, themes, styles, etc., which we observe particularly from the mid-1960s and later (apart from the quantitative increase of the Greek women writers), was not without cause. Various factors contributed to this. First, the female immigrants now differed from those of the pre-World War II years, and especially from the mid-1960s most of them had more formal education. Second, they did not come almost exclusively from small rural areas in Greece. At the same time Greece itself had changed, and therefore many of the female immigrants had a more modern outlook. On the other hand, life in the foreign land increased their social stimuli and widened their experiences.

Moreover, what contributed significantly to their literary writing was the post-World War II press. The massive growth in the number of Greeks in Australia resulted in a corresponding growth in the Greek press (newspapers, periodicals, etc.). Comparatively from the few pre-World War II publications, the press after the War increased impressively. For example, in the decade of the 1950s 19 new publications started circulating, 28 in the 1960s, 32 in the 1970s, and 18 in the 1980s (Kanarakis, 2000, passim and especially pp. 130-141).

Significantly, most of the publications encouraged literary contributions, while some of them included literary pages or even had literary supplements, thus giving existing writers an outlet for the publication of their works and at the same time encouraging new writers. It is significant that almost all the Greek-language writers (men and women) who later published books first appeared in the pages of the community press of Australia (Kanarakis, 1989, pp. 169-174).

In addition to all these effective factors, from 1972 the Australian government’s implementation of a new public policy of multiculturalism as a major strategy which emphasised immigrant rights, cultural pluralism and removal of “barriers to immigrants’ economic, social and political opportunities” (Castles, 1992, pp. 186-192) benefitted Greek women writers, as well. Immigrants were now encouraged to maintain their language and the culture of their native lands, while Australians were encouraged to become more interested and appreciative of the nation’s cultural diversity. Furthermore, the newly founded Australia Council and other organisations began to show interest and offer financial assistance for translations of immigrants’ literary works, the staging of their plays, etc. This support encouraged Greek women writers even more because they realised for the first time that their literary work was valued beyond the boundaries of the Greek community.

In addition to all these effective factors, from 1972 the Australian government’s implementation of a new public policy of multiculturalism as a major strategy which emphasised immigrant rights, cultural pluralism and removal of “barriers to immigrants’ economic, social and political opportunities” (Castles, 1992, pp. 186-192) benefitted Greek women writers, as well. Immigrants were now encouraged to maintain their language and the culture of their native lands, while Australians were encouraged to become more interested and appreciative of the nation’s cultural diversity. Furthermore, the newly founded Australia Council and other organisations began to show interest and offer financial assistance for translations of immigrants’ literary works, the staging of their plays, etc. This support encouraged Greek women writers even more because they realised for the first time that their literary work was valued beyond the boundaries of the Greek community.

From the viewpoint of language, although the literary production of Greek women writers in pre-1952 times was exclusively in Greek, now it appears in both Greek and English. Their first English-language literary texts were published early in the 1960s in Australian literary journals. Antigone Kefala was the first English-language writer who has developed into one of the most noted and versatile English-language Greek women writers in this country.

In contrast to the fact that in recent years the influx from Greece and Cyprus of new Greek-language writers in general has almost been eclipsed, the English-language writers have been increasing markedly in all literary genres and is predicted, as is to be expected, to overtake its Greek counterpart in the future.

Another distinguishing characteristic between pre- and post-World War II literary production is that the Greek women writers of the latter period were not restricted to publishing in the press but they also made their presence felt with publications in book form. The first book to be published was the Greek-language poetry collection Droplets by Vasso Kalamara published in Athens in 1959. Correspondingly, the first English-language book (also a poetry collection) was The Alien by Antigone Kefala, published by the Australian Publishing Company Makar in 1973. It is worth noting that this collection was also the first book by a Greek woman writer to be published in Australia. Since then, especially in more recent years, quite a large number of books by Greek women writers have been published in Greek, in English, in bilingual formats, as well as in English translation.

The talent and the contribution of a number of these women, both Greek and English-language writers, have been recognised as evidenced by the prizes they have received in literary competitions in Greece, Cyprus or within the Greek community of Australia and, as regards the English-language writers, in Australia as well. It is also apparent in the increasing number of Greek Australian, Australian and Greek publishing houses issuing their works.

Today we see a constantly growing interest in the literary works of Australia’s Greek women writers. There have been successful conferences focussing on their activities,2 in addition to books and articles in this area.3 Furthermore, anthologies devoted exclusively to Greek women writers have been compiled, in addition to those general collections which include their works4 and a number of MA and PhD theses which have focussed on them,5 with interest further increasing and broadening in our times. Two contemporary indicative examples are first, the decision of the editorial committee of the periodical Antipodes of the Greek-Australian Cultural League of Melbourne to dedicate this issue (No. 57, October 2011) to the contribution made by Greek women poets and writers, and second, the English-language poetry anthology Southern Sun, Aegean Light: Poetry of Second-Generation Greek Australians (2011), selected and edited by Dr Nick Trakakis, which includes women poets, all exclusively second generation.

The Greek woman as writer in Australia is, therefore, of special interest. Her presence on the literary scene, whether as poet, prose writer or playwright, is notable and has become more conspicuous since the 1950s, and nowadays has become even more prominent in both Greek and English-language literature, the latter particularly among those who emigrated at a young age and were educated in Australia or are the daughters or granddaughters of first generation Greek women immigrants.

The Greek women writers in Australia, as in other countries of the Greek diaspora, despite living in a generally male-dominant society, especially in pre-World War II times, have proved that they would never be restricted from expressing themselves. Their need to put their thoughts, emotions and life experiences into words has prevailed. The work of these writers, both past and contemporary, reflect not only their personal stories but provide us with a historical body of work spanning almost a century, presenting significant and relevant insights into the Greek communities of their times. They form part of our “collective memory”, and furthermore enhance their rightfully deserved position, deriving not just from their talent but also from their endurance and dedication, and not only as part of the entire literary tapestry of the Greeks in Australia but also importantly of Global Hellenism in general.

ENDNOTES:

Endnotes

1 In the 1970s I discovered a number of oral versifications but all of them by men created in the Greek community environment of the coffee house or in social gatherings (Kanarakis, 19912, passim), as well as a few anonymous ones in folk form.

2 For example, the conferences Greek Women Writers from Σαπφώ to Sappho at RMIT, Melbourne, in 1992 and Women Writers of the Greek Diaspora organised by the General Secretariat for the Greeks Abroad, Greek Ministry for Foreign Affairs in 1997, the proceedings of the first edited by Konstandina Dounis (1994) and of the second by Marianna Spanaki (bilingual edition, 2001).

3 Indicatively see Helen Nickas’ book Migrant Daughters: The Female Voice in Greek-Australian Prose Fiction, Melbourne: Owl Publishing, 1992.

4 See, for example, the bilingual work Re-Telling the Tale: Poetry and Prose by Greek-Australian Women Writers edited by Helen Nickas and Konstandina Dounis (1994), as well as Mothers from the Edge: An Anthology (2006) and Women of the Antipodes: Greek-Australian Short Stories (2008), the former edited and introduced, and the latter edited, introduced and translated into Greek by Nickas. All three works have been published by Owl Publishing, Melbourne.

5 For example, see Helen Nickas’ MA thesis entitled The Female Voice in Greek-Australian Prose Fiction (The University of Melbourne, 1990) and Marie Gaulis’ PhD thesis Une littérature de l’exil: Vasso Kalamara et Antigone Kefala, deux écrivains grecs d’Australie (Genève: Éditions Slatkine, 2001).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Demographic Statistics, June Quarter, 1984, Canberra: AGPS, 1984.

Castles, Stephen S., “Australian Multiculturalism: Social Policy and Identity in a Changing Society” in Gary P. Freeman and James Jupp, eds, Nations of Immigrants: Australia, the United States and International Migration, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1992, pp. 184-201.

Department of Immigration, Australian Immigration Consolidated Statistics, No. 2, Canberra: AGPS, 1968.

Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, Australian Immigration Consolidated Statistics, No. 13, 1982, Canberra: AGPS, 1983.

Kanarakis, George, “The Greek Press in Australia: A Social and Literary History”, Modern Greek Studies Yearbook, Vol. 5, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1989, pp. 163-179.

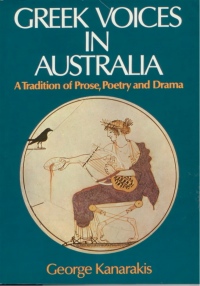

Kanarakis, George, Greek Voices in Australia: A Tradition of Prose, Poetry and Drama, Sydney: Australian National University Press, 19912.

Kanarakis, George, The Greek Press in the Antipodes: Australia and New Zealand, (Series: Hellenism of the Diaspora, No. 1), Athens: Grigoris Publications, 2000 [In Greek].

Kanarakis, George, Aspects of the Literature of the Greeks in Australia and New Zealand, (Series: Hellenism of the Diaspora, No. 2), Athens: Grigoris Publications, 2003 [In Greek].

Tsounis, M.P., Greek Communities in Australia, (Ph.D. thesis), The University of Adelaide, 1971.

Dr. George Kanarakis is an Adjunct Professor in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Charles Sturt University in Australia.