- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

Four Brief Secular Holiday Essays |

This month’s theme:

Four Brief Secular Holiday Essays

The title says it all. Happy holidays, whatever holidays you celebrate.

Essay #1:

Prayer and Hope

By David M. Fitzpatrick

There’s a popular observation about atheists at Thanksgiving—that when atheists want to be thankful, they have no one to thank. It’s a narrow-minded viewpoint, one that assumes that the only one to thank about anything is a deity. I can’t speak for all atheists, but when I feel like thanking someone, I thank SOMEONE—an actual person. During a Thanksgiving meal, I am more apt to thank the person who cooked the meal or bought the food or made the pies. I might thank the company that employs me, or the person there who hired me, for without the paycheck I might not be able to celebrate Thanksgiving at all. Most of all, I thank the friends and family who spend time with me on that day.

I suppose it’s a matter of perspective. Religious folks feel the need to thank invisible gods. Atheists don’t. It might be a fine line; after all, we both experience feelings of gratefulness. And from my experiences, most religious people who thank their gods are also apt to be appreciative of real live people as well. Maybe we’re not so different.

We might be similar in other ways. Consider prayer, the religious practice of a follower allegedly communicating with his god. They feel that their gods hear them during these prayers (and some claim their gods talk back, but that’s a topic for another essay), and they invoke prayer as a marvelous catch-all—to thank the god, to ask the god for help, to seek guidance from the god, etc. I guess atheists have nothing to match that; we typically feel that taking action is a far more effective way to get things done. We thank actual people, we ask actual people for help, we seek guidance from actual people.

But what about those situations when people feel as if they have no options to actually act, but are desperate for an outcome to go a certain way? They pray in hopes that a loved one won’t die, that a lost dog will come home, that a hurricane won’t destroy a home. I still think there is action to be taken—being with that loved one, searching for the lost dog, engaging in proper emergency preparedness.

But I get it: Sometimes you’ve done all that you can do, and all that is left is that feeling of desperation—desperation from the understanding that you have done all that you can do, taken all the action that you can take, and that you are helpless to do anything further to make a difference. All you can do now is wait. It only makes sense that one who believes in a deity will pray like mad.

I do something similar. I don’t pray, of course, but once I have done all that I can do and I am beset with that feeling of desperation, I hope. I hope like mad. George Carlin once observed that praying to God and praying to Joe Pesci are essentially the same thing, with each having the same chance of success—about 50/50. The same can be said of prayer versus hope. But of course there’s a basic difference between prayer and hope. Prayer assumes that a higher power is listening, and if your prayers are strong enough, or if enough people pray for the same thing, the deity will act on it to direct what will happen.

Hope, on the other hand, is the product of someone who understands that the outcome will happen however it will happen, and no higher power will change it. If I want a certain film to win Best Picture at the Oscars, I know that the choice has been made before the announcement airs, listed on a card in an envelope. I HOPE that my film is the one, but I know that no amount of hope will change it if another film is already on that card.

The holidays are times when I think more people pray more often. Maybe they have greater needs. Maybe people just want to be happier during this season and really want things to go well. Maybe they think that, during the holidays, their gods are a bit more soft-hearted and more receptive to requests.

Maybe the reality is that prayer and hope are both ways of the human brain talking to itself. For each of us, the entire universe is really what is contained in one’s brain, regardless of what you believe or don’t believe. If that’s the case, then my only desire is that people who pray don’t entirely surrender to their faith, and instead use that brain to think things through.

Maybe there IS more action you can take before relegating yourself to talking to gods.

Maybe prayer can lead people to deeper critical thinking and self-reflection, and guiding themselves to logic and reason and intellect when making decisions—especially when those decisions affect others.

Maybe thinking instead of just praying might lead people to understanding that the rights and dignity of others should be absolute, and not subject to what another person believes.

At least, I certainly hope so.

Essay #2:

Including Everyone

By David M. Fitzpatrick

Recently, there has been a war on Christmas.

At least, that’s what the Bill O’Reillys of the world tell us. Since around 2005, there has been fierce opposition to retailers not using “Christmas” in their advertising, based on the paranoid belief that everyone is trying to get rid of Christmas. The reality is that everyone is just trying to be inclusive of all religions and holidays; for instance, in the United States there are 5 to 7 million Jewish people celebrating Hannukah and shopping at those retailers.

One of the key arguments is that retailers kept trying to use terms like “Happy Holidays” and “Season’s Greetings” instead of “Merry Christmas”—arguments that have also been used against the government using similar language. But the reality is that this is nothing new. “Season’s Greetings” dates to Victorian times, and has been a staple in the United States for a hundred years on greeting cards and in advertising. “Happy Holidays” has also been commonly used for a century.

The issue, of course, isn’t any imagined war on Christmas. It’s inclusiveness of everyone. It’s easy in a Christian-dominated culture for anyone—even an atheist like me—to just assume everyone celebrates Christmas. I remember working at a store over 20 years ago; on Christmas Eve, I asked one of the other employees if he were ready for Christmas. He was Jewish; I knew this, and if I didn’t his last name—Goldstein—should have tipped me off. He was clearly disheartened at my question, which really had been thoughtless but unintentional; I felt awkward and wished him happy holidays and left. I have said “Happy holidays” to people ever since.

But I meant no offense. I think he knew that. But today’s angry demands that everyone say “Merry Christmas” seems to be very intentionally offensive to me. The numbers of Christians in the U.S. is dropping fast as there are more non-Christians here. Numbers for atheists and agnostics continue to rise, as well as the numbers of those who merely do not subscribe to any particular religion.

No one is waging a war on Christmas. The only war being waged is by certain Christians on everyone else. Maybe it’s because they’re afraid of non-Christians (particularly those with brown skin) increasing in population here; perhaps it’s because they feel that their religion is slowly fading away, like most religions are, and like they all eventually will, into history.

All of this strikes me as amusing, in a sad way. For the Christians furious at the use of “Season’s Greetings” and “Happy Holidays,” their biggest targets are retailers. They’ve organized boycotts of retailers who don’t say “Merry Christmas.” But here’s the thing: I’m pretty sure that if Jesus were a real person and showed up for the second coming today, he wouldn’t approve. He wouldn’t approve of the rampant capitalism that runs our society, and the cultural requirement that we all spend a pile of money every year to buy gifts from those retailers, all in the name of his birthday. Okay, there’s no way for me to know WHAT Jesus would think, but Christians love to claim that they know, so it doesn’t hurt for me to do it. Based on the Jesus from the Bible, I think my guess is pretty good.

It’s not that giving gifts is a bad thing. I’m an atheist, and I celebrate Christmas, and I give a lot of gifts. And certainly it would be nice if we didn’t have to have this one time of year when we give gifts and try to be a little nicer to each other. But we DO have that one time of year. The fact is, without it we might find that nothing unites us in annual goodwill.

So I’ll participate in the gift-giving. I’ll celebrate the winter solstice, and I’ll say “Happy Holidays” to people I don’t know well enough to guess their religious leanings. If I know they’re Christian, I’ll gladly say “Merry Christmas,” because that’s what’s important to them. If they’re Jewish, I’ll say “Happy Hannukah” because that’s what’s important to them. And when I say “Happy Holidays,” I know that some of them who are Christian will look annoyed and respond with “Merry CHRISTMAS!” just to make sure I know what’s right.

But it would be great if people could not be so angry and anti-anything-not-Christian about it. It would be nice for them to hear my wish of “Happy Holidays” and take it as it was intended—that I want them to enjoy their holidays. It isn’t about a war on Christmas. It isn’t meant to lessen their religion. It’s just about goodwill and good cheer.

It’s not about a religious agenda, or it shouldn’t be. It really should be about us all having happy holidays—whatever those holidays are.

Essay #3:

Another Trip Around the Sun

By David M. Fitzpatrick

Why do you celebrate the holidays this season? Is it Christmas? Hannukah? Kwanzaa? Something else entirely?

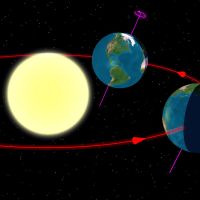

I like to tell people that I celebrate the winter solstice, which means that our planet has made another successful trip around the Sun. This is nothing new. Since prehistoric times, humans figured out the seasons, and even when they thought the Sun moved around the Earth, they still understood that the Sun was lower or higher in the sky depending on the season, and the amount of time the Sun was in the sky was shorter or longer.

Those primitives knew about four points of the year, which we observe today. The solstices are the days when the Sun is in the sky the longest and the shortest (the summer and winter solstices). The equinoxes are the periods at the halfway points between the solstices (the vernal and autumnal equinoxes), when the lengths of day and night are equal.

Indeed, in the Northern Hemisphere, many of the December holidays have their roots in the winter solstice. Christmas has Christian roots, allegedly the birth of Christ, but the gift-giving tradition comes from the Roman celebration of Saturnalia. In brief, once Christianity took hold of the Roman Empire, it was quickly obvious that the festival of Saturnalia—once to honor Saturn, the chief god of the Roman pantheon—had become well-established as a secular holiday across the empire, and it wasn’t going anywhere. The people just loved it too much. So the Christians co-opted Saturnalia and declared it the birthday of Jesus. There were other factors, such as Christian scholars arguing for Christ’s birth to be represented by the shortest day of the year.

Jesus wasn’t the only one. Egyptians celebrated the birth of the god Horus at the winter solstice, for example. And winter festivals celebrating all manner of religious icons and secular reasons have occurred during the winter solstice for thousands of years. The Christians felt that all of these pagan holidays needed to go, but more often absorbed them and made them part of their religion than abolishing them completely. Indeed, many Protestant sects, such as the Puritans, did not celebrate Christmas as one point or another because it wasn’t biblical; Jehovah’s Witnesses today don’t celebrate Christmas.

For me, I love the idea that we’ve survived another trip around the Sun without completely destroying ourselves. Every religion has its own reasons for celebrating the winter solstice, whether it’s the birth of a god’s son or the recognition of a religious historical event. But no matter one’s religion, or if one has no religion, it’s easy for us all to celebrate the solstice. It’s universal; half the world sees its longest day and half its shortest, depending on which hemisphere you’re in, northern or southern. And every solstice means that the planet has orbited the Sun and ended up right where it was a year ago.

The world certainly needs something to agree on. Extremely ferocious religious folks rarely do. What better than the universal idea of the planet completing an orbit? And in an age where religionists refuse to believe in evolution, conservatives refuse to believe in global climate change, and fundamentalists refuse to believe that the Earth is more than 6,000 years old, we really need a basic scientific proof to agree on. Orbiting the Sun is, for all but the most ignorant Flat Earthers and geocentric types, the best example of this. That is, unless people start disbelieving in the theory of gravity, I suppose.

So I’m celebrating that trip around the Sun. More than that, I’m looking ahead to another successful trip, which has only just begun.

Essay #4:

Bringing It All Together

By David M. Fitzpatrick

I bet the preceding essays make me look like a religion hater. I’m really not.

In the United States, by law we have freedom of and from religion. In practice, there are many who seem determined to deny those who don’t share their religion of the right to observe their own. They want to keep all Muslims out. They want to deny same-sex marriage. They want to bring government-led prayer back into public schools. They want all taxpayers to fund their religion, but don’t want their tax dollars to fund anything that they disapprove of.

I’d rather that people keep their religions to themselves. But I am a fierce champion of everyone’s right to believe in anything. Whether you want to follow God, Jehovah, Allah, Thor, Zeus, Quetzalcoatl, the Flying Spaghetti Monster, Eris, Bob, or no one, have at it.

If you want to follow the tenets of the Jedi or the philosophy of Vulcan, knock yourself out. And you’ll notice that followers of the Jedi and Vulcans are never the ones fighting to deny others their religious freedom. Vulcans, in fact, follow the idea of IDIC—Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations. That alone is a lot more tolerant and inclusive than many religious people I know.

The problem is the old adage about how one bad apple spoils the barrel. It isn’t that every Christian is a raving lunatic bent on destroying everything non-Christian—far from it! But those bad apples… there are a bunch, and all they do is spoil barrels wherever they go.

I don’t want religion destroyed. I just want the religious maniacs—the hateful, intolerant, sadistic, dictatorial few who work to rally the many to their maniacal causes—to go away.

I won’t pray. I will hope.

I won’t offend. I will include all with “Happy Holidays.”

I won’t look back. I will look forward—to another trip around the Sun, and social progress the world over.

I hope you have happy holidays, and enjoy the next orbit with me.

Best,

-David M. Fitzpatrick

David M. Fitzpatrick is a fiction writer in Maine, USA. His many short stories have appeared in print magazines and anthologies around the world. He writes for a newspaper, writes fiction, edits anthologies, and teaches creative writing. Visit him at www.fitz42.net/writer to learn more.