- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

Cud Flashes In The Pan |

This Month’s Theme:

“All Things Lit”

So The Cud’s editor, Evan Kanarakis, reminded me that it was the annual “All Things Lit” issue. Normally, this means contributors can write about anything, and longer than usual. In other months, Evan likes to stick to around 2,000 words, so the reader doesn’t get bored or lost. As anyone who reads this space monthly knows, I tend to hit 3,000 words. Evan’s pretty good about it, what with me arguing that since this is flash fiction, and each piece is brief, I can go longer without it reading long, and so on. He smiles and nods and tells me he trusts my judgment, although secretly I suspect he’d like to slap me around every now and again.

Which brings us to this month’s very slap-worthy column. We’ll start with a 525-word speculative-fiction flash piece. Then we’ll move on to a 725-word sword-and-sorcery poem (from a guy who is absolutely not a poet). Then we’ll utterly abandon the concept of “flash” with a 3,000-word non-speculative, mainstream story.

And even though we’ll already be at 4,250 words, I’ll even throw in an 8,700-word story in the form of a PDF ebook, free for download for readers of The Cud. Currently, this is available only to people clicking through from this page. If you like it and would like friends to read it, I’d ask that you send them to this page instead of forwarding the ebook; that way, we’ll know how many people chose to download it—and, hey, more people get introduced to the grass-munching writing that is The Cud.

In February, it’s going to be really difficult to get back to shorter stuff.

“Up Shit Creek”

Dark Fantasy

By David M. Fitzpatrick

When Wilbur bought the land, there had never been a homestead there. He did his business in the woods for the few weeks he took to build a log cabin, a tool shed, and a small barn for his horse and few animals, but he knew he needed an outhouse. And that meant digging a fairly deep hole to accommodate the crapper.

He headed out early one morning, shovel in hand, searching for a suitable place, when he stumbled on the big slab of gray slate amidst a wild tangle of overgrown brambles. Etched on it, white marks on gray, was a message:

A DEMON LIVES BENEATH!

DO NOT RELEASE HIM!

Unlike most folks on the frontier, Wilbur wasn't superstitious. He knew the warning was bunk, so he pried up the slab with his shovel and dragged it aside. Beneath was a hole, its rim lined with jagged stone. It was just two feet wide and descended into blackness. He fetched a lantern, lit it, and shone it into the hole. It seemed to go down forever.

He struck a match and tossed it in, and watched as it flickered its way deep down and out of sight. It had to have been a hundred feet at least.

Wilbur couldn't believe his good fortune. He didn’t have to slave away digging a crap hole; there was one already there, a natural shaft that appeared to be so deep he’d never have to worry about digging a new one. He'd never crap enough in his lifetime to fill up that bottomless pit.

So Wilbur built an outhouse over the hole and began crapping in it that day. It served him well for the first week of his tenure at his homestead; he pissed off his back steps as a rule, but every morning he'd make a trip to the outhouse, drop his drawers, and give back to the earth.

But on the eighth day, he had just finished his business when the ground began to rumble beneath him. The outhouse shook, and the wood split. He leaped off the seat, hollering as he burst out the door. He staggered backward, grabbing his trousers as the cold morning air chilled his bare ass through the open flap of his union suit. He watched in horror as the outhouse rattled mightily.

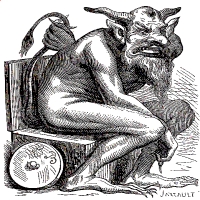

Smoke billowed out of the hole, and a crimson glow blazed out of the ground. The outhouse began to come apart, even as it caught fire. Black smoke poured high into the sky. And then something in the hole exploded, blowing the flaming wood everywhere... and there, in the rolling smoke, a massive black-red thing was forming.

Wilbur looked on, mortified, as the demon took shape. It was nine feet tall, shoulders broader than a buffalo, horns on its head, eyes blazing yellow, skin like scorched red leather. The beast towered above him, baring rows of sharp teeth as fire burned in its throat. And the massive demon reached a massive clawed hand out, pointing an accusing finger at Wilbur, and when the demon spoke it was a roaring baritone:

"Motherfucker!" the demon cried. "Stop shitting in my living room!"

“The Fantasy Film Festival”

Poem – Sword & Sorcery

By David M. Fitzpatrick

Okay, I’m not a poet, but this poem is more a social commentary. If only our own world could better embrace positive things like imagination and creativity instead of destruction and oppression, it just might be a better place. Who knows, maybe Hollywood could make a difference on another world. Yes, I know, there are other movies besides American; but it’s what I know. Imagine your own favorite movies being watched by enthralled elves and dragons. It’s easy—and imagination is what this is all about.

In the wooded green valley of Farvale

On a world ten dimensions away

Uneasy Elves and Dwarves gathered

For Lizard Men joined them this day

Then Ogres and Goblins soon came there

The Gnomes and the Centaurs as well

They set aside their ancient quarrels

For this pandemic truce in the dell

Kobolds arrived and Trolls wandered in

Orcs by the fives and Gnolls by the tens

Halflings and Pixies and Hobbits galore

Hobgoblins, Bugbears, Giants, and more

And then came the legions of Humans

They were led by a noble old Wizard

In flowing blue robes and white hair

He called the strange meeting to order

With a great flash of light in the air

As the magical colors subsided

And silence fell over the crowd

He cast a great spell that created

A giant rectangular shroud

Humanoids oohed and eyebrows raised

Everyone ahhed and faces blazed

Another spell cast, the sky became night

Everyone gawked as the shroud came alight

“You’ve seen nothing yet,” said the Wizard.

“I’ve traveled to worlds with my magic

Through this limitless, vast multiverse

And on one I’ve found something so wondrous

And you will all now see it first

It’s like nothing you’ve ever before seen

But don’t fear—for it’s not the least tragic

It’s just that you’ve never beheld this:

It’s a grand technological magic.”

Spoken words, muttered commands

Wild gestures, waving hands

A puff of smoke, a flash of light

Blazing thunderbolts, a mighty sight

And the gigantic sheet came to life.

Images moved on the canvas

And with them came marvelous sounds

Everywhere humanoids cried out

And all nearly fell to the ground

Music poured out through the green vale

And sounds that they couldn’t explain

The Wizard then cast yet one more spell

And new languages entered their brains

“They’re called ‘movies,’ wonderfully wrought

They’ll stir your emotions, awaken your thoughts

So I ask you, my friends, for today, set aside

Our battling old ways, and take a wild ride.”

And the great wizard turned to watch.

They heard stories of Southern plantations

And of Major Kong riding a nuke

They saw tales of great expectations

Of cuckoo’s nests and Cool Hand Luke

They watched as the Death Star exploded

Kirk and Spock and the Enterprise crew

There was Citizen Kane and his Rosebud

Norman Bates and his hotel, too

Shawshank redemptions, lords of rings

Musical numbers where everyone sings

Shark-attack scenes and Replicant types

Stories in colors, and some black and white

And that was just the first weekend.

Humanoids came from all over

To see all the great wonders there

And dragons joined in to experience it

Winging their ways through the air

The Wizard cast spells to accommodate

Increasing the size of the screen

It spanned the whole width of the valley

By thousands of souls it was seen

Offers you can’t refuse, chariots of fire

Trenchcoat gumshoes, werewolves, vampires

Schindler, flux capacitors; lost arks, silent lambs

Life is like chocolates; “Make my Day,” “Play it, Sam.”

“Gort! Klaatu barada nikto!”

A mutiny at sea on the Bounty

And Robin who steals from the rich

Trips ‘round the world by Day Eighty

Suffering the seven-year itch

Aliens that burst through your ribcage

Or those with glowing heart lights

From outer space back to the Old West

To LaMutha’s and Balboa’s fights

Two thousand one, infernos in towers

Seeing dead people, superhero powers

Five until Wapner, trips to the moon

Ol’ Davy Crockett and ol’ Daniel Boone

Computer realities, unsinkable ships

Miss Daisy driving, time-travel trips

All they’d imagine, and so much more

They saw no end to this filmdom lore

Dramas, romance

Butch, Sundance

Sci-fi, thrillers

Horror, killers

Ben-Hur, history

Poirot, mystery

Grand animations

Great imaginations

And everyone watched

And everyone saw

They lived those films

They lived in awe

And they came to a new understanding

The peoples now gather each season

A meeting of so many nations

They celebrate their global unity

Through another world’s wondrous creations

To London, New York, and Tokyo

To Middle-Earth, Narnia, and Oz

No matter wherever they visit

The show always ends with applause

And the Wizard keeps traveling, always unraveling

New films for the worldwide affair

Next year he’ll present motion pictures from “Tee-Vee”

And everyone’s sure to be there

At the Fantasy Film Festival

“The Hellbound Express”

Mainstream

By David M. Fitzpatrick

I think I’m going to die soon. I think I have to. But I have to tell this story first. If I’m weak enough to kill myself, I have to know that others will understand. But I have to go back thirty years to tell this story.

The only major road in Hallibont is the state route the truckers use coming out of the northern woods, and those eighteen-wheelers scream past our houses like stock cars on that rural highway. From the time we could walk, our parents fiercely warned us to keep away from it. Everyone’s front yards in Hallibont are bordered with fences, as if they’d somehow protect everyone from speeding tractor-trailers. They’d be about as effective as paper in keeping trucks from ending up in your living room. And the fences don’t hide the diesel roars of the trucks as they rumble steadily past, like an endless freight train.

But the danger was always the fun with Danny Burkman and me. He lived two houses down, and we’d been best friends since kindergarten. He was the one with all the great ideas and the courage to take chances. I always tagged along. He was the leader and I was the follower, and I was always okay with that.

We spent our summers riding the dirtbike trails, building treehouses, and swimming in Mellow Pond; but when we grew tired of those things, the trucks entertained us. What we did for that entertainment seemed incredibly funny; then again, we thought the same thing about calling our town of Hallibont “Hellbound.” We got that from Danny’s dad; when a big truck would barrel past and shake the house, he’d say “There goes the Hellbound Express,” and we’d laugh insanely, as if it were the funniest thing we’d ever heard. That’s the beauty of being ten years old.

The house between mine and Danny’s belonged to Mr. Callahan, a senile, house-ridden old man for whom we often did yard work for spare change. But his expansive property was our personal playground—and the long hedge in his front yard, bookended and shaded by giant oak trees and bordering the dangerous road, was the front line of that playground, like the ultimate useless fence against the Hellbound Express.

The ground there was a veritable sea of fallen acorns, like a million tiny skulls crunching beneath giants’ feet. We’d hoard them by the hundreds, creating a stockpile hidden within the thick hedge. We’d placed two rocks in there to sit on, like command chairs; they were the size and shape of footballs, only flat, a few inches thick. Comfortably ensconced in our base of operations, we were dangerously close to the narrow road—just three feet from the gravel shoulder. With our acorn arsenal at the ready, we’d wait until a big truck rumbled around the bend up ahead, and we’d throw dozens of those acorns onto the asphalt, creating a strip of acorn carpet across the road that no truck could miss.

“Hellbound Express!” we’d scream crazily, and then the truck would roar past like a freight train, just feet from our hidden faces, and flatten the acorns. We’d laugh and cheer over the flattened mess, but then we’d scurry out, scoop up the survivors, add more acorns to the mix, and wait for the next truck. We felt invincible hidden away in the hedge, as if it were some kind of armored fortress that protected us.

But nearing the end of the summer, with the specter of school looming over us, even that activity was losing its appeal. We’d sent countless acorns to their deaths, and it was beginning to look as if a green-brown pile of puke had been ground into the road. We sat there on our flat, football-shaped rocks; they seemed less like command chairs and more like useless old rocks. I was bored but didn’t dare to say it. Danny saved me from that, and I wish more than anything that he hadn’t.

“Acorns ain’t fun no more,” Danny said, his voice dry but final.

“Yeah,” I said.

He thought hard, his face framed by the green branches of our hiding place. Finally, he brightened and smiled. “Crabapples!”

It was an unbelievable revelation. We ran to Danny’s garage for some buckets and then out to Mr. Callahan’s back field to fill them. Soon, we were rolling them onto the road at the sound of an approaching truck, then diving back into our safe haven where nothing in the world could touch us.

“Hellbound Express!” we screamed.

The massive tires of the speeding truck made instant applesauce, spraying it all over us in the hedge. We were delirious with laughter.

The apples kept us going for a few days, but eventually that novelty wore off even as the crabapple supply ran out. One evening, with school a week away, we hung out in one of our treehouses. We were ignoring a blood-red sunset, trying to think of something to do. I wish we’d stopped to admire the sunset. Maybe if we’d understood then how something so beautiful was worth just watching, instead of feeling that we had to be doing something stupid, things would be so different now.

Danny abruptly said, “We need something better than crabapples.”

I couldn’t imagine how anything could top the crabapples, but Danny always had the best ideas. He said, “I bet tomatoes from your folks’ garden would smush really good.”

I couldn’t have agreed more, but my parents would have killed me when they found out. I told Danny this, but the truth was, if he’d insisted, I’d have given in. But he thought hard some more.

“I’ve got it,” he finally said. “Follow me.”

I’ll never forget the gleam in his eyes. We should have just done the tomatoes.

He ran for the hedge and I followed blindly, not knowing his idea but not caring; it would be a good one, because Danny’s always were. That’s why he was the leader.

We made it to our foliage fortress and I sat on my flat rock, but Danny didn’t. Instead he dropped to his knees and picked up his flat rock. He held it up, presenting it like a trophy bass. It was big for a ten-year-old kid—as long and wide as a football, mostly flat, a few inches thick. Immediately, I felt uneasy.

“You can’t put a rock in the road,” I said. “You might cause an accident.”

“A rock ain’t causing no accident,” he said with a snort and a look on his face that said I can’t believe this kid is so stupid.

“My Uncle Jack hit a rock with his car,” I said. “He drove off the road and into a ditch.”

“Yeah, a car,” Danny argued. He was always so persuasive. “These are huge trucks. They could drive over rocks twice as big as this and it wouldn’t hurt ‘em. And this kind of rock—a truck’ll smash it into dust.”

“Well, do a smaller one,” I said, because something still gnawed at me. “A handheld one.”

“No, the truck’d just roll over a small one and not even know it. But one this size would be like hitting a big pothole. The truck will bounce a little and turn this thing into pebbles. It’ll be so cool.”

We debated it while he strained to hold the rock, but of course eventually I relented and let him lead. He was the smart one, after all.

The sun had set and it was dark. Passing cars had their headlights on. We hid in our safe spot and waited until there were no cars in sight, waiting for the telltale rumble of a big truck down around the bend. At night, we could see the glow of their headlights a good fifteen seconds before they came into sight—all the time in the world to litter the road with acorns or crabapples or rocks.

Finally, we heard the familiar sound of a big truck’s diesel growl. “Here it comes,” I said.

“I got it,” he said, grunting as he yanked up the rock and leaped out of the bushes. He moved quickly into the road and dropped it with a THUNK just inside the yellow line. Far down the road, the glow of the roaring truck’s headlights brightened as it was about to come around the bend.

“Hurry!” I hissed.

He kicked it into final position with his foot and bolted back to the hedge, leaping in beside me with an excited laugh.

We took up our positions and waited.

The lights flashed into view, and our eyes had to adjust. The truck bore down on us, blinding us with two sets of headlights: one upper, one lower, along with the line of five orange lights atop the cab. We could hear exhaust hissing madly out the smokestack.

“Hellbound Express!” Danny screamed over the roar of the engine.

“Hellbound Express!” I echoed, and we laughed crazily.

And then the headlights shifted. The lower set seemed to move independently of the upper set.

There was a car in front, the tractor trailer riding its ass. Danny realized it, too, even as I said, “Car!”

“Shit!” he hollered, and he came out of his crouch, planning to leap out of the hedge, to race into the road and get the rock—but it was too late. He’d be run down. I grabbed his arm and hauled him back as the car arrived.

It must have been doing sixty when its left front wheel hit the rock. It lurched sideways, tires squealing as it went up on two wheels. It tore past us and then it flipped over in a scream of twisting metal.

The truck locked up its brakes even as its own front tire slammed into the spinning rock, and the whole tractor bounced into the air. By the time it slammed back down, the car was on its roof, spraying a shower of sparks as it slid.

The tractor went sideways and the truck jackknifed. Both vehicles were well past us as the semi slammed into the car and both of them left the road in a shower of sparks.

The car crashed into a tree and the truck smashed into the car, and in a final wail of screeching metal, the semi wrapped itself around the tree and the crushed car and everything was silent.

We sat in our hideout, stunned and speechless. Steam spewed from the the wrecked truck, and fuel gurgled onto the road. Nothing moved.

“Holy shit,” Danny said, breathless.

“What do we do?” I said, my voice quaking.

Danny thought for a moment, his eyes frozen on the scene, his brow high and frightened. Then he leaped out of the hedge and bolted into the road. He had to run a good twenty feet to find it, but he got his hands on the rock and hefted it. He hurried clumsily back, even as fresh headlights lit up the bend ahead.

“Car!” I hollered.

He made it to the hedge and heaved the rock. It crashed through the branches and tumbled to the ground in our hideout, and Danny leaped back into our spot as the car came into view.

***

The driver of the car stopped even as Danny’s parents and mine came rushing out of our houses. Soon there were emergency vehicles everywhere. They brought hydraulic equipment to pry apart metal, but there was nobody alive to rescue.

We watched from the hedge, unable to move throughout the entire ordeal. When there were only tow trucks left to clean up the mess, we walked, numb, back to Danny’s house.

“What do we do?” I asked him when we got to his driveway.

He watched the flashing orange lights for a minute before he said, “Nothing. We don’t tell anyone.”

“I think we have to,” I said. I was weak; I was scared.

But I was a follower, so when Danny gave me a hard look and said, “No, we don’t,” I listened.

***

They decided that the truck lost control and plowed the car off the road.

The truck driver had been one for thirty years, and that truck had been his life. That, and the Labrador retriever in the cab with him. He and the dog had traveled every road east of the Mississippi and plenty west of it. Officially, the accident was that guy’s fault. Probably fell asleep at the wheel, they said.

The young couple in the car had been married two years. He’d just landed a big job and they’d moved to the area. She was pregnant, due in just a month. Their first child, an infant, had been in the back seat.

They were all dead. And we’d killed them.

***

We didn’t talk about it until the night before school was to start, when we returned to the scene of the crime. We just sat in the hedge in the dark, watching cars and trucks speeding past. We didn’t say a word for a good half hour.

It was dark when bright headlights lit up the bend ahead, and we could hear the rumbling of the truck’s big diesel engine. Danny picked up a stray acorn and said, “Hellbound Express,” and lazily tossed it into the road.

The truck roared by and missed the acorn, but the chasing gust of wind grabbed it and rolled it away, down the road and into the dark of night.

Eventually another rumbling truck lit up the bend. I picked up a few stray acorns, and Danny did the same. “Hellbound Express,” we told each other, and halfheartedly tossed the small bunch into the road. Presently, the truck arrived and blew past, smushing some of the acorns, missing others.

Danny said, “What happened was wrong.”

“I know,” I said, relieved to hear him say it. “We gotta tell someone what we did.”

“We don’t ever tell nobody,” he said. “It was me, anyway, not you.”

“I shoulda stopped you.”

He rolled his eyes at me. “You’ve never been able to stop me from doing anything.”

He was right, of course. “So what do we do?”

“You don’t ever tell anyone,” he said. “Understand? As long as you live, you never breathe a word of this to anyone.”

I nodded dumbly. Danny knew best.

“No nods,” he said sharply. “You gotta promise me—the most excellent promise ever. You have to promise you’ll never tell anyone about what happened.”

“I promise,” I said, numb and terrified, and wondering if I could keep that promise.

Another truck was coming, so I scrambled for a handful of stray acorns and tossed them into the road. They tumbled about in the dark as I said, “Hellbound Express.”

“Hellbound Express,” Danny echoed, but he hadn’t thrown any acorns.

“You didn’t toss any,” I told him. “You’re not supposed to say ‘Hellbound Express’ unless you toss acorns.”

He sat in silence as the headlights of the roaring truck lit up the road. Eerie shadows of the thousand branches in the hedge waltzed across Danny’s face as it closed on us, on the acorns.

“Hellbound Express,” Danny said, and I could barely hear him.

It was screaming down on us, just a house or two away, when Danny leaped out of the hedge like a jack-in-the-box before I realized what he was doing, ran two steps, and threw himself down onto the road.

The truck driver never had a chance to stop. By the time he went for the brakes, he was already rolling over Danny. I screamed mindlessly for my best friend as he was ripped to bits beneath the massive wheels.

But I knew, in that moment, that I would keep my promise.

***

Thirty years is such a long time to live with guilt like that.

I’ve survived three failed marriages that collectively produced seven kids who all hate me, just like their mothers. They’d all been good women; I was the louse who drank and drugged, lied and cheated. I’ve never had a career, never held a job for long. My rusting Chevy is almost as old as Danny’s death. Forty years on the planet, and nothing to show for it.

My house is the only thing I own, and it wasn’t earned through any accomplishments of my own; I got it when my mother died. The place is like a prison; I’ve spent a lifetime trying to forget what happened, and now I eat and sleep and dream and screw and watch TV less than a hundred feet from where it all happened.

I find myself out there alone at nights, sitting in the hedge. It’s overgrown these days, but our spot is still there. I don’t throw acorns, but I do watch the trucks’ lights shining around the bend and bearing down on me. Every time one screams past, I see Danny’s body getting torn apart, and I feel his blood spatter my face again. And I think of those others who died, and I wonder if any of them felt any pain.

I don’t think Danny did. I suppose he thought he was paying the ultimate price for what he’d done, but all he did was make sure he didn’t have to live with what happened. But I’d lived with it for three decades. I’ve suffered for both of us.

I sit out there, watching the trucks scream by, hoping against hope one will lose control and crash through the hedge and kill me. I know the chances are extremely remote, so I fight the urge to do just what Danny did. I fight it because I don’t deserve that easy way out. I deserve to live with it as long as my body will last, even if I live a hundred more years.

But I’m not like that. I’m a coward. And I’m a follower.

Sooner or later, I know I’ll follow Danny. I get weaker every night—weaker with every truck that roars past. One of these nights I won’t be able to take it anymore, and I won’t make it to see the truck go by.

And, God help me, I think I hear the Hellbound Express coming now.

“Cone Zero, Sphere Zero”

Dystopian Science Fiction

By David M. Fitzpatrick

It’s time for a departure from flash fiction. The PDF you can download here is a story that has appeared twice in print. The first was in Des Lewis’ Cone Zero, from his renowned Nemonymous series. Recently, I reprinted it in an anthology I edited called Atheist Tales. That anthology, full of great stories by many talented writers, was quite a pleasure to edit. It also completely blows the “flash fiction” concept of this column completely out of the water.

Download “Cone Zero, Sphere Zero” here!

David M. Fitzpatrick is a fiction writer in Maine, USA. His many short-stories have appeared in print magazines and anthologies around the world. He writes for a newspaper, writes fiction, edits anthologies and teaches creative writing. Visit him at www.fitz42.net/writer to learn more.