- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

Controversy In History: On A.J.P Taylor’s The Origins of the Second World War |

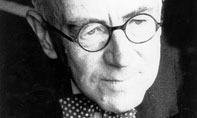

From its first publication in 1961, A.J.P Taylor's book, The Origins of the Second World War has been at the heart of controversy because of his unorthodox treatment of  Hitler's contribution to the outbreak of war. Key to Taylor's study is the proposition that Hitler (whilst in part guilty for contributing to the outbreak of WWII), should not be charged with complete blame for the war, as if any countries were in error, it was the allied countries like Britain and France, rather than Germany alone, that were more at fault.1 Hitler, Taylor argues, did not aim or plan for war, he simply took opportunities, and was in fact an ordinary statesman of the period, in the same mould as both his predecessors and contemporaries (like Stresemann and Hollwegg). Where Hitler had territorial aims or expansionary goals, many of these were justified, as in Taylor's view Germany had a basic, intrinsic right to much of the territory in her region (e.g Danzig).2 It is in the framework of these general arguments that Taylor clearly supports the inference that WWII was in many aspects a resumption of the WWI conflict. In Taylor's eyes, WWII was “... a war which had been implicit since the moment the first war ended.”3

Hitler's contribution to the outbreak of war. Key to Taylor's study is the proposition that Hitler (whilst in part guilty for contributing to the outbreak of WWII), should not be charged with complete blame for the war, as if any countries were in error, it was the allied countries like Britain and France, rather than Germany alone, that were more at fault.1 Hitler, Taylor argues, did not aim or plan for war, he simply took opportunities, and was in fact an ordinary statesman of the period, in the same mould as both his predecessors and contemporaries (like Stresemann and Hollwegg). Where Hitler had territorial aims or expansionary goals, many of these were justified, as in Taylor's view Germany had a basic, intrinsic right to much of the territory in her region (e.g Danzig).2 It is in the framework of these general arguments that Taylor clearly supports the inference that WWII was in many aspects a resumption of the WWI conflict. In Taylor's eyes, WWII was “... a war which had been implicit since the moment the first war ended.”3

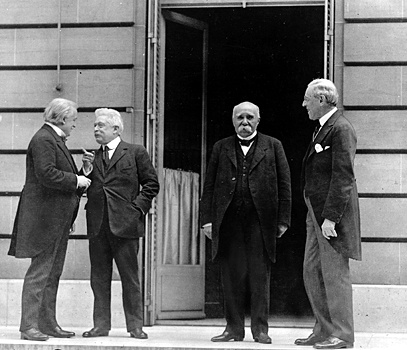

One of the profound (and not necessarily controversial) causes of WWII which is brought out in Taylor's thesis is the extent to which the peace settlement of Versailles in 1919 failed to prevent a German revival of power, and a renewal of conflict in 1939. The key elements of the peace treaty included the dismantling of Germany's colonial empire, the loss of some of  her surrounding territory (such as Alsace-Lorraine to France), limitations upon Germany's future military capabilities, a German war debt set at $32 billion, and later the notorious war guilt clause 231. Despite such seemingly restrictive measures upon Germany, Taylor and others4 have argued that the Versailles Treaty was ineffective, because it failed to provide an answer to the question of German power on the continent, in fact still leaving Germany in a united and strong enough position to reject Versailles from the very outset in 1919. Additionally, though it is not borne out to any significant degree in Taylor, the peacemakers have often been condemned for not taking economic factors and nationalism into account when re-organizing the various territories of Europe.5 The artificial geographic arrangements that were designed at Versailles left large groups of Germanic people outside of their homeland (leaving open the possibility of future demands for re-unification), and thus needed some form of support to work. But with domestic electoral pressure on both the U.S and British governments to withdraw from major political involvement on the continent (the American Senate refused to ratify the Versailles Treaty), France was left in a precarious overseer position, paranoid of another German reprisal of power.

her surrounding territory (such as Alsace-Lorraine to France), limitations upon Germany's future military capabilities, a German war debt set at $32 billion, and later the notorious war guilt clause 231. Despite such seemingly restrictive measures upon Germany, Taylor and others4 have argued that the Versailles Treaty was ineffective, because it failed to provide an answer to the question of German power on the continent, in fact still leaving Germany in a united and strong enough position to reject Versailles from the very outset in 1919. Additionally, though it is not borne out to any significant degree in Taylor, the peacemakers have often been condemned for not taking economic factors and nationalism into account when re-organizing the various territories of Europe.5 The artificial geographic arrangements that were designed at Versailles left large groups of Germanic people outside of their homeland (leaving open the possibility of future demands for re-unification), and thus needed some form of support to work. But with domestic electoral pressure on both the U.S and British governments to withdraw from major political involvement on the continent (the American Senate refused to ratify the Versailles Treaty), France was left in a precarious overseer position, paranoid of another German reprisal of power.

Other signs of weakness existed. Germany retained seven-eighths of her former size in Europe, and Article 231 was interpreted as placing all of the blame for WWI upon Germany, making it a great source of resentment. Snell also adds that Versailles did nothing to deal with the powerful industrialists of Germany (who played such a crucial role in WWI, and were to be of such importance in WWII), and though the settlement restricted Germany's military, it left little restriction upon her traditional leaders who were to become powerful enemies of the new republic.6 “Judged pragmatically it (the treaty) created a German desire for revenge that would last, and a weakening of Germany that was only transitory.” 7 The failures of the League of Nations only served to highlight this aspect.

Other signs of weakness existed. Germany retained seven-eighths of her former size in Europe, and Article 231 was interpreted as placing all of the blame for WWI upon Germany, making it a great source of resentment. Snell also adds that Versailles did nothing to deal with the powerful industrialists of Germany (who played such a crucial role in WWI, and were to be of such importance in WWII), and though the settlement restricted Germany's military, it left little restriction upon her traditional leaders who were to become powerful enemies of the new republic.6 “Judged pragmatically it (the treaty) created a German desire for revenge that would last, and a weakening of Germany that was only transitory.” 7 The failures of the League of Nations only served to highlight this aspect.

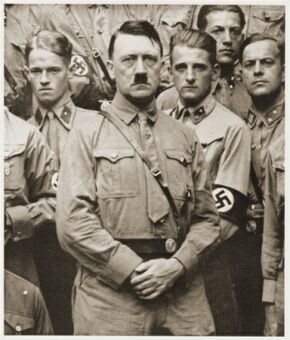

As has been mentioned, however, Taylor's book is controversial in its treatment of the role of Hitler. Unlike such authors as H.S Hughes, Alan Bullock, A.L Rowse, and most specifically Hugh Trevor-Roper,8 Taylor refuses to place primary responsibility for the war on the shoulders of Hitler. He writes, “In principle and doctrine, Hitler was no more wicked and unscrupulous than many other contemporary statesmen”, but because of his horrific actions during the war historians of the post war period, inflamed by emotion and patriotism, have written unfavourable accounts of Hitler as being the sole cause of WWII.9 In analysing the extent to which Hitler caused the war, Taylor discards the importance of the documents Mein Kampf and the Hossbach Memorandum as mere “daydreaming”, and of little relevance in suggesting that Hitler had “planned” for a war.10

Key to this aspect of Taylor's argument is that the allies (in particular Britain and France) were as much, if not more to blame for causing the war, not merely because of the weaknesses of the Versailles Treaty, but in their failed policy of appeasement towards Germany and other fascist nations. The principle argument behind appeasement rested on the fear that if the dictator's demands were not met it could lead to war, a war in which the dictators could either win, or else fall and remove themselves as a barrier to the new threat of communism. In accordance with the policy of appeasement, Hitler's decision in March 1938 to annex Austria was met with initial shock, but later acceptance, in the argument that he had merely re-united Germans. More importantly, Taylor highlights the Munich Conference of September 1938 (where the allies allowed Germany the Sudetenland) and the Molotov-Ribbentrop Nazi/Russian Non-Aggression Pact of August 1939, as being examples of the allies “blundering” into giving Hitler territory, and yet leaving him desiring for more. Hitler did not make precise demands. He announced that he was dissatisfied and then waited for the concessions to be poured into his lap, merely holding out his hand for more."11

Key to this aspect of Taylor's argument is that the allies (in particular Britain and France) were as much, if not more to blame for causing the war, not merely because of the weaknesses of the Versailles Treaty, but in their failed policy of appeasement towards Germany and other fascist nations. The principle argument behind appeasement rested on the fear that if the dictator's demands were not met it could lead to war, a war in which the dictators could either win, or else fall and remove themselves as a barrier to the new threat of communism. In accordance with the policy of appeasement, Hitler's decision in March 1938 to annex Austria was met with initial shock, but later acceptance, in the argument that he had merely re-united Germans. More importantly, Taylor highlights the Munich Conference of September 1938 (where the allies allowed Germany the Sudetenland) and the Molotov-Ribbentrop Nazi/Russian Non-Aggression Pact of August 1939, as being examples of the allies “blundering” into giving Hitler territory, and yet leaving him desiring for more. Hitler did not make precise demands. He announced that he was dissatisfied and then waited for the concessions to be poured into his lap, merely holding out his hand for more."11

Hitler's demands in 1939 for Danzig and other regions of Poland were, in Taylor's opinion, justified to some extent, and the stubborn defiance of the Polish, and the obvious repercussions of the Anglo-Polish alliance dictated the course of events that led to Germany's invasion of Poland and the allied declaration of war in September.12 War was thus caused more by blunder than design to the extent that the allied countries grossly overestimated Germany's power and the character of Hitler in appeasing him more and more, whilst Hitler's greatest blunder was that he did not suppose the two Western Powers would go to war at all.13

Hitler's demands in 1939 for Danzig and other regions of Poland were, in Taylor's opinion, justified to some extent, and the stubborn defiance of the Polish, and the obvious repercussions of the Anglo-Polish alliance dictated the course of events that led to Germany's invasion of Poland and the allied declaration of war in September.12 War was thus caused more by blunder than design to the extent that the allied countries grossly overestimated Germany's power and the character of Hitler in appeasing him more and more, whilst Hitler's greatest blunder was that he did not suppose the two Western Powers would go to war at all.13

There is some merit in Taylor's book. Whilst most will tend to clearly agree to with Trevor-Roper that we cannot discount Mein Kampf and the Hossbach Memorandum as suggesting that Hitler had early designs for territorial expansion and war,14 and that Hitler was, in policy, not “just another statesman”,15 it is also crucial to avoid concentrating on simplistic histories of the period that are overly moralistic or subjective in nature, particularly in their treatment of Hitler. What is so important about Taylor's thesis is not that he finds Hitler innocent, for his conclusion is far from this. What Taylor does make clear, however, is that everyone involved in the period deserves to share some degree of blame, whether it was the Germans, British, French, Russians, Poles or even the Czechs.

The Second World War was thus in many respects very much a resumption of the First. The Versailles settlement was neither strong enough nor practical enough to prevent a future German reprisal of power, and attempts at safeguarding the faulty peace settlement and preventing a resumption of conflict were unsuccessful. Nothing was done to deal with the serious issue of growing German nationalism. Questions about the role of German power and leadership on the continent were not answered in WWI but in September 1939 –undoubtedly aided along by the longstanding designs of one Adolf Hitler- matters finally, tragically, would come to a head.

The Second World War was thus in many respects very much a resumption of the First. The Versailles settlement was neither strong enough nor practical enough to prevent a future German reprisal of power, and attempts at safeguarding the faulty peace settlement and preventing a resumption of conflict were unsuccessful. Nothing was done to deal with the serious issue of growing German nationalism. Questions about the role of German power and leadership on the continent were not answered in WWI but in September 1939 –undoubtedly aided along by the longstanding designs of one Adolf Hitler- matters finally, tragically, would come to a head.

End Notes:

- Thus Taylor is in opposition to the decision of the Nuremburg Trials, where he states documents were specifically chosen “... not only to demonstrate the war-guilt of the men on trial, but also to conceal that of the prosecuting Powers... The verdict preceded the tribunal; and the documents were brought in to sustain a conclusion which had already been settled.” Taylor, A.J.P., The Origins of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 1982, p.36.

- “Danzig was the most justified of German grievances...” See Ibid., pp.264-266.

- Ibid., p.241.

- Such as Wicks, Peter, German Policy and the Origins of the Second World War, History Teacher's Association of N.S.W, Doonside, 1972, p.12, and Snell, John. L., Illusion and Necessity-The Diplomacy of Global War, 1939-1945, Tulane University Press, 1963, p.2.

- J. M Keynes, in "The Economic Consequences of the Peace", highlighted clearly the poor economic aspects of Versailles. See Wicks, op.cit., p.15. Discussion on the important role of nationalism as a cause of WWII can also be found in Thomson, David, World History, From 1914 to 1961, Oxford University Press, 1964, pp.103-112, and in Snell, op.cit., p.3.

- Ibid., p.2. Wicks adds: "...the treaty was neither severe enough to hold the Germans down forever, as the French had desired, nor sufficiently generous to reconcile the defeated powers in their new situation."Wicks, op.cit., at p.2, and p.15.

- Snell, op.cit., p.2.

- See Hugh R. Trevor-Roper, “Hitler's Plan For War Reaffirmed”, in Snell, op.cit., p.2., pp.88-97.

- “...in wicked acts he outdid them all.” Taylor, op.cit., p.100.

- Ibid., pp.168-170.

- Taylor further explains: "He did not "seize" power. He waited for it to be thrust upon him by the men who had previously tried to keep him out." Ibid., p.101. Marshall Dill adds that “...Hitler did not plan events in advance; no-one can do that with exactness.” Dill, Marshall, Germany: A Modern History, University of Michigan Press, 1961, p.382.

- As a consequence “...the French who had preached resistance for twenty years appeared to be dragged into war by the British who for twenty years had preached conciliation.” Ibid., p.335. See also pp.264-266.

- Ibid., p.335.

- Hugh Trevor-Roper in Snell, op.cit., Note pp.91-94.

- Taylor's study in fact brings out “...important differences between the Weimar Republic's foreign policies and those of Hitlerian Germany.” Hiden, John,Germany and Europe, 1919-1939, Longman Books, London and New York, 1977, p.159.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Dill, Marshall,

Germany: A Modern History

, University of Michigan Press, 1961.

Hiden, John,

Germany and Europe, 1919-1939

, Longman Books, London and New York, 1977.

Snell, John. L.,

Illusion and Necessity-The Diplomacy of Global War, 1939-1945

, Tulane University Press, 1963.

Taylor, A.J.P.,

The Origins of the Second World War

, Penguin Books, London, 1982.

Thomson, David,

World History, From 1914 to 1961

, Oxford University Press, 1964.

Wicks, Peter,

German Policy and the Origins of the Second World War

, History Teacher's Association of N.S.W, Doonside, 1972.