- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

‘Getting It Right’ |

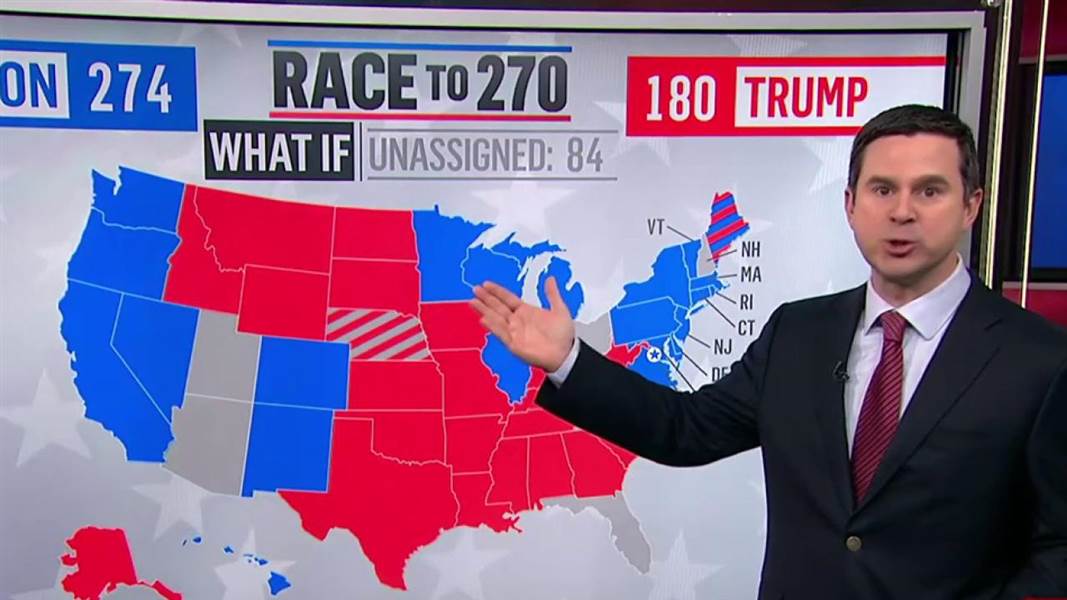

It was sad to see how much time Australian media devoted to the US elections of November 2016. Even worse perhaps was the unsurprising concentration on only some candidates in only one poll. As the results became clear however, much commentary was devoted to the odd idea that the media ‘got it wrong’. Many astute observers would no doubt agree that the media coverage of these elections did fail in many ways, but surely, only a journalist could imagine that the shortcomings relate exclusively to predictions of the result.

Consumers of media, naive creatures as we may be, cling to a belief that the main role of media is to report events as they happen. It is also legitimate to explain the range of possibilities ahead such as psephologists do, but it is another matter entirely to try to predict what will happen in an election campaign. Australian media do not understand why local voters behave as they do let alone how voters in the US behave.

Apart from this practical difficulty relating to lack of understanding however, there is an important question here about media ethics. In the same way that opinion polls carry an element of the self-fulfilling prophesy, media prognostications about electoral outcomes smack of an attempt to wield power. When candidates take note of media predictions, they tend to court the favour of the commentators and so deliver power into their hands.

There was a by-election in the New South Wales state seat of Orange at the weekend following the big US ballot. In the week before the poll, two prominent shock-jocks from Sydney went to the town and campaigned hard against the National Party. The National Party is in Coalition with the Baird Liberal Government and has held Orange for generations. The shock-jocks no doubt recognised that the time was right for a maverick outsider to shake the Nationals’ grip on the seat and set out to exploit voter discontent over a number of issues. Perhaps the most prominent concerns among locals were the decisions to ban greyhound racing and to amalgamate local government areas.

Following the huge swing against the Nationals a party room meeting in Macquarie Street ousted leader Troy Grant. Apparently National Party MPs felt that they had been expressing concerns about these policies but that Grant had backed Liberal Party decisions for the sake of Coalition unity. Grant had been particularly associated with the ban on greyhound racing and had stood firm despite threats of violence to himself and his family. Interestingly, the Minister pushing Council amalgamations, Bathurst MP Paul Toole, attracted less criticism.

It is pointless to speculate whether the swing against the Nationals and the purge of leadership would have been as great without the intervention of the shock-jocks. There is however, little doubt that these commentators know that they wield enormous power. Nor is it surprising that when the result of the US presidential election became clear, journalists asked how the media could have been so mistaken about the likely result. Media workers themselves asked this question because they are the ones who believe that they should have been able to predict the result - either that or that their predictions should have determined the result. They seemed to be amazed that the candidates and the voters ignored their predictions! What an incestuous world they inhabit.

Now that the dust has settled in the USA, the media are at again. Hours and acres of commentary have been devoted to how President Trump will behave. Having failed to understand Trump’s campaign rhetoric, media commentators quickly turned their dubious skills towards likely developments in the next four years. Perhaps they might derive some consolation from being able to claim that they did warn us about a Trump presidency but it is difficult to understand why we media consumers should give them this second chance to fail.

There is a valid lesson that media should learn from their failure to predict a Trump victory. It is that predicting the future should not be the central role of media. This preoccupation with punditry arises in a hankering after power. Some media workers might express disdain for shock-jocks but most harbour a taste for that kind of authority. Clearly however, the general community would be better served if media abandoned this fantasy and returned to the important task of reportage.

A former academic, Tony Smith has written extensively on a wide range of subjects as diverse as folk music and foreign policy issues in the Australian Review of Public Affairs, the Journal of Australian Studies Review of Books, Overland, the Australian Quarterly, Eureka Street, Online Opinion and Unleashed.